sx blog

Our digital space for brief commentary and reflection on cultural, political, and intellectual events. We feature supplementary materials that enhance the content of our multiple platforms.

Boston Review Publishes David Scott's Essay on C.L.R. James

Boston Review Publishes David Scott's Essay on C.L.R. James

In anticipation of a new edition of The Black Jacobins by C.L.R. James, check out this essay by David Scott on “C.L.R. James’s Radical Vision of Common Humanity” published by Boston Review.

Small Axe 70 is now available!

Small Axe 70 is now available!

This issue includes essays by Najnin Islam, Sasha Ann Panaram and Tohru Nakamura. Wayne Modest and Susan Legêne guest-edit the special section entitled "Anton de Kom and the Caribbean Intellectual Tradition" -- with contributions by Mitchell Esajas, Markus Balkenhol, Olivia Gomes da Cunha, Karwan Fatah-Black and Guno Jones. This issue's visual essay and cover image feature IMPRINT by Shannon Alonzo. The book discussion engages Reimagining Liberation: How Black Women Transformed Citizenship in the French Empire by Annette K. Joseph-Gabriel with essays by Grace Sanders Johnson, Shanna Jean-Baptiste, and Tobias Warner.

Take a look at the table of contents: http://smallaxe.net/sx/issues/70

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE): Lila, cimarrona de les arbumanes

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE): Lila, cimarrona de les arbumanes

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), a small-scale independent publisher, established in 2009 in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, is proud to announce the release of its most recent titles to the Caribbean’s ample and diverse public.

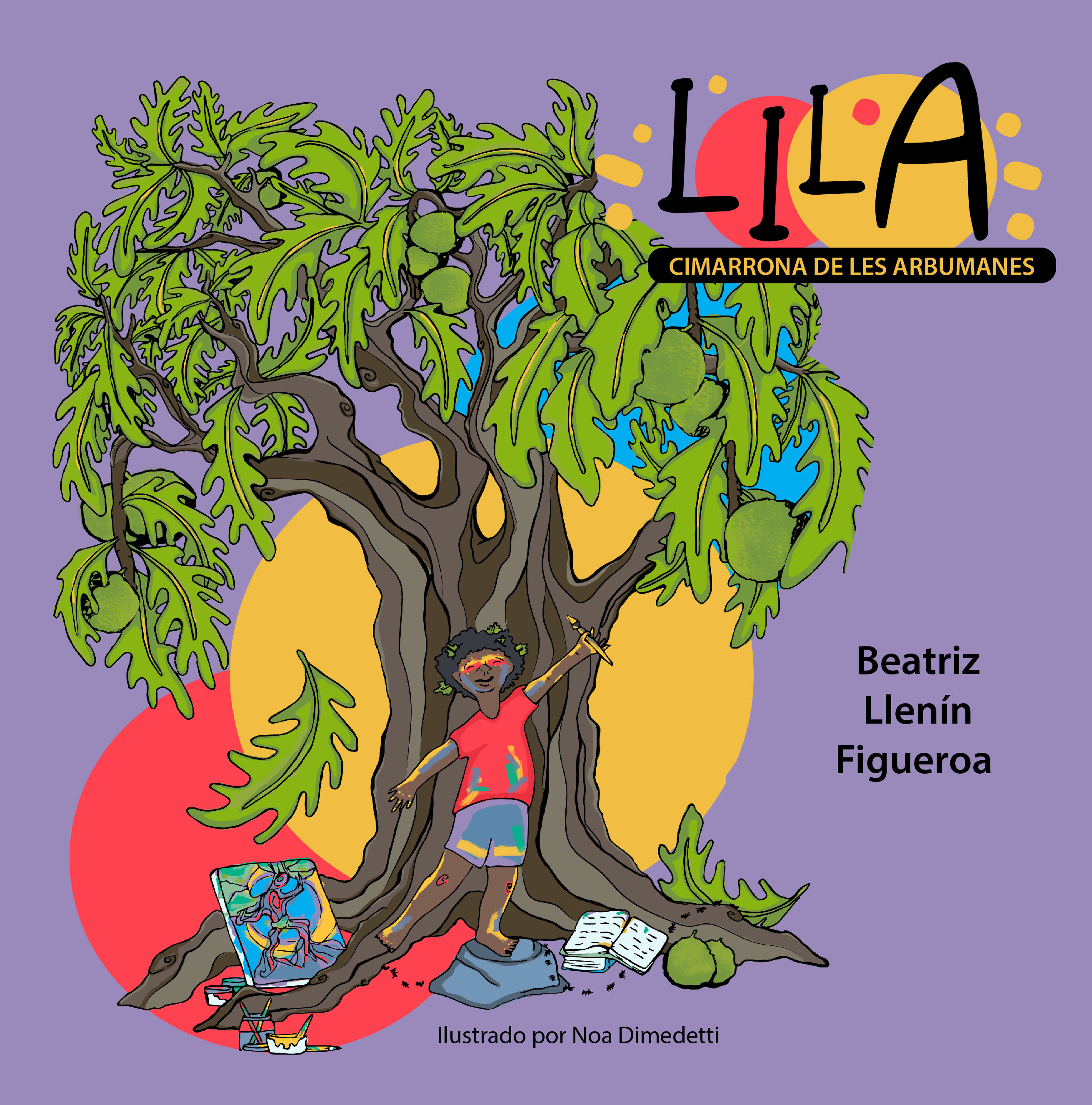

To our Otra escuela series we have also added Lila, cimarrona de les arbumanes, by Beatriz Llenín Figueroa and with illustrations by Noa Dimedetti. This is a story for late childhood, early adolescence, or any age of innocence. Lila, who has chosen her own name, contemplates her surroundings’ wonders and delights herself eating boiled breadfruit and learning about the Caribbean region. Meanwhile, she envelops us in her wonder and passion for study, diversity, nature, art, and imagination. Supported by her diverse family –the wonderful Grandma Bo and her two moms, who are present, even if they’re gone–, Lila manages to change everything.

To explore our complete catalogue of over seventy titles, please visit: portal.editoraemergente.com To purchase our books, please visit us online: editoraemergente.com Or come to Puerto Rico, where you can find our titles in local bookstores.

Nuevos títulos de Editora Educación Emergente (EEE):

Lila, cimarrona de les arbumanes

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), proyecto editorial independiente de pequeña escala, fundado en 2009 y con base en Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, presenta al amplio y diverso público caribeño sus seis títulos más recientes.

A la serie Otra escuela también se añade Lila, cimarrona de les arbumanes, de Beatriz Llenín Figueroa y con ilustraciones de Noa Dimedetti. Este libro es un relato para la niñez tardía, la temprana adolescencia o cualquier edad de la inocencia. Lila, que ha escogido su propio nombre, contempla las maravillas de su entorno y se deleita comiendo pana hervida y aprendiendo sobre la región caribeña. Mientras, nos envuelve en su asombro y pasión por el estudio, la diversidad, la naturaleza, el arte y la imaginación. Apoyada por su familia diversa –la maravillosa abuela Bo y sus dos mamás, quienes están, aunque se hayan ido–, Lila logra cambiarlo todo.

Para explorar nuestro catálogo completo, con más de sesenta títulos publicados hasta la fecha, visita: portal.editoraemergente.com Para adquirir nuestros libros, visita las librerías locales puertorriqueñas o nuestra tienda en línea en: editoraemergente.com

Nouveaux titres d’Editora Educación Emergente (EEE) / Éditrice Éducation Émergente (EEE):

Lila, cimarrona de les arbumanes

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), projet d’édition indépendant à petite échelle, fondé en 2009 et basé à Cabo Rojo, Porto Rico, présente ses six titres les plus récents à l’ample et divers public caribéen.

Lila, cimarrona de les arbumanes ( Lila, marronne des arbumanes ) , de Beatriz Llenín Figueroa, avec des illustrations de Noa Dimedetti, s'ajoute également à la série Otra escuela (Une autre école ). Ce livre est un conte pour la fin de l'enfance, le début de l'adolescence ou n'importe quel âge d'innocence. Lila, qui a choisi son propre nom, contemple les merveilles de son environnement et se régale à manger du fruit à pain bouilli et à découvrir la région des Caraïbes. En attendant, elle nous enveloppe dans son émerveillement et sa passion pour l'étude, la diversité, la nature, l'art et l'imagination. Soutenue par sa famille diversifiée – la merveilleuse grand-mère Bo et ses deux mamans, qui sont là même si elles sont parties – Lila parvient à tout changer.

Pour explorer notre catalogue complet, avec plus de soixante titres publiés à ce jour, visitez : portal.editoraemergente.com Pour acheter nos livres, visitez les librairies portoricaines locales ou notre boutique en ligne à : editoraemergente.com

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE): Crudo 69: piezas selectas de un año de escritura salvaje

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE): Crudo 69: piezas selectas de un año de escritura salvaje

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), a small-scale independent publisher, established in 2009 in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, is proud to announce the release of its most recent titles to the Caribbean’s ample and diverse public.

Crudo 69: piezas selectas de un año de escritura salvaje by Kisha Tikina Burgos Sierra was published as part of our Otra escena series. This book unabashedly continues the author’s craft of writing live arts pieces from a dual perspective: our pained and courageous Puerto Rico, and the femme and feminized bodies in their multiform experiences. Favored by her continuous work as actress, producer, and director of theatrical and cinematographic pieces, Burgos Sierra gifts us pieces and words already conceived for translation onto the live body on stage or behind the camera, and not merely to be savored through the literary reading usually associated with conventional drama. Thus, the experimentation that characterizes this collection results not only from its plots and contents, which oscillate between the visceral and the symbolic, flesh and abstraction, lived and longed-for experiences, but it is also verified in the sharp stage directions and in the concentrated, accelerating forms of these brief pieces. As the author explains with other words in her prologue, the selected texts constitute the alchemical precipitate of a moment of deep pain and creation that she, inspired by the African American dramatist Suzan-Lori Parks’s equivalent exercise, accompanied with daily writing over an entire year.

Nuevos títulos de Editora Educación Emergente (EEE):

Crudo 69: piezas selectas de un año de escritura salvaje

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), proyecto editorial independiente de pequeña escala, fundado en 2009 y con base en Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, presenta al amplio y diverso público caribeño sus seis títulos más recientes.

Crudo 69: piezas selectas de un año de escritura salvaje de Kisha Tikina Burgos Sierra se añade a nuestra serie Otra escena. Este libro continúa con arrojo el oficio de escribir piezas de artes vivas desde un anclaje dual: nuestro Puerto Rico adolorido y aguerrido, y las cuerpas femme y feminizadas en sus multiformes experiencias. Favorecida por su continua labor como actriz, productora y directora de piezas teatrales y cinematográficas, Burgos Sierra nos ofrece piezas y palabras concebidas de antemano para traducirse en el cuerpo vivo en escena o tras la cámara, y no meramente para degustarse por medio de la lectura literaria que asociamos con el drama convencional. La experimentación que caracteriza esta colección, por tanto, no es sólo el resultado de sus tramas y contenidos, que oscilan entre lo visceral y lo simbólico, entre la carne y la abstracción, entre lo vivido y lo ansiado, sino que también se constata en las filosas acotaciones y en la forma concentrada, galopante, de estas piezas breves. Como la autora explica con otras palabras en su prólogo, los textos seleccionados constituyen el precipitado alquímico de un agujero propio de dolor y creación que acompañó con escritura diaria a lo largo de un año, inspirada por el equivalente ejercicio de la dramaturga afroestadounidense Suzan-Lori Parks.

Nouveaux titres d’Editora Educación Emergente (EEE) / Éditrice Éducation Émergente (EEE):

Crudo 69: piezas selectas de un año de escritura salvaje

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), projet d’édition indépendant à petite échelle, fondé en 2009 et basé à Cabo Rojo, Porto Rico, présente ses six titres les plus récents à l’ample et divers public caribéen.

Crudo 69: piezas selectas de un año de escritura salvaje ( Brut 69 : pièces choisies d’une année d’écriture sauvage ) de Kisha Tikina Burgos Sierra s’ajoute à notre série Otra escena ( Una autre scène ). Ce livre poursuit avec audace l'art d'écrire des œuvres d'art vivant à partir d'un double ancrage : notre Porto Rico douloureux et endurci au combat, et les corps féminins et féminisés dans leurs expériences multiformes. Favorisée par son travail continu d'actrice, productrice et metteuse en scène de pièces théâtrales et cinématographiques, Burgos nous offre des pièces et des mots conçus à l'avance pour être traduits dans le corps vivant sur scène ou derrière la caméra, et pas seulement pour être savourés à travers la lecture littéraire, que nous associons au drame conventionnel. L'expérimentation qui caractérise cette collection n'est donc pas seulement le résultat de ses intrigues et de ses contenus, qui oscillent entre le viscéral et le symbolique, entre la chair et l'abstraction, entre le vécu et le désiré, mais se confirme aussi dans les vives dimensions et dans la forme concentrée et galopante de ces courtes pièces. Comme l'explique en d'autres termes l'auteure dans son prologue, les textes choisis constituent le précipité alchimique de son propre trou de douleur et de création qu'elle a accompagné d'une écriture quotidienne pendant un an, inspirée de l'exercice équivalent de la dramaturge afro-américaine Suzan-Lori Parcs.

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE): El otro camino: la historia de un pequeño ñu

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE): El otro camino: la historia de un pequeño ñu

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), a small-scale independent publisher, established in 2009 in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, is proud to announce the release of its most recent titles to the Caribbean’s ample and diverse public.

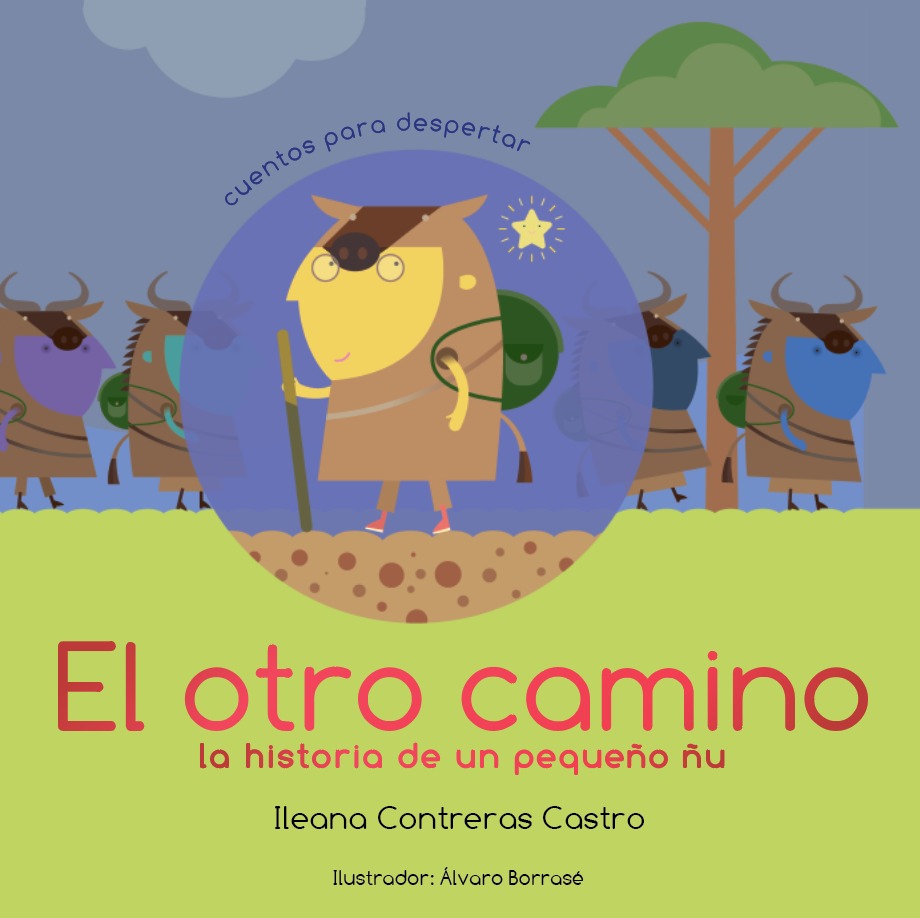

Our Otra escuela series is amplified with the children’s story El otro camino: la historia de un pequeño ñu by Ileana Contreras Castro and illustrated by Álvaro Borrasé. Werevu, a small and intelligent gnu, attentively observes the behavior of adults and dares to question some of their irreflexive habits. When he goes unheard, Werevu decides to change and do something different from his pack. Full of courage and doubts, the path he takes through the African savannah is, really, that of living consciously. This takes him to the encounter with a constellation of diverse animals whose common characteristic is choosing freedom as the most precious good. Having literature with critical ideas without losing the writing’s craft and beauty, as is the case in this book, is a welcome fact, and one that offers its readers the possibility of asking themselves whether they really must graze in the eternal fields of custom. This is a book only for big people, regardless of their age.

Nuevos títulos de Editora Educación Emergente (EEE): El otro camino: la historia de un pequeño ñu

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), proyecto editorial independiente de pequeña escala, fundado en 2009 y con base en Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, presenta al amplio y diverso público caribeño sus seis títulos más recientes.

La serie Otra escuela se amplía con el relato infantil El otro camino: la historia de un pequeño ñu de Ileana Contreras Castro e ilustrado por Álvaro Borrasé. Werevu, un ñu pequeño e inteligente, observa muy atento lo que hacen los adultos y se atreve a cuestionar algunos de sus hábitos irreflexivos. Al no ser escuchado decide dar un giro y hacer algo diferente a su manada. Lleno de valentía y dudas, el camino que toma por la sabana africana es en realidad el de vivir de forma consciente, y éste lo lleva al encuentro con una constelación de animales diversos, cuyo rasgo común es la elección por la libertad como el bien más preciado. Es un acierto tener literatura con ideas críticas como las aparecidas en este libro que, sin perder la belleza de su escritura, ofrece a sus lectores la posibilidad de preguntarse si de verdad hay que pastar en los eternos prados de la costumbre. Éste es un cuento sólo para gente grande, sin importar su edad.

Nouveaux titres d’Editora Educación Emergente (EEE) / Éditrice Éducation Émergente (EEE): El otro camino: la historia de un pequeño ñu

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), projet d’édition indépendant à petite échelle, fondé en 2009 et basé à Cabo Rojo, Porto Rico, présente ses six titres les plus récents à l’ample et divers public caribéen.

La série Otra escuela (Une autre école) se prolonge avec le conte pour enfants El otro camino: la historia de un pequeño ñu ( L'autre sens : l'histoire d'un petit gnou ) d'Ileana Contreras Castro et illustré par Álvaro Borrasé. Werevu, un petit gnou intelligent, observe attentivement ce que font les adultes et ose remettre en question certaines de leurs habitudes irréfléchies. N'étant pas écouté, il décide de faire demi-tour et de faire quelque chose de différent pour sa meute. Plein de courage et de doutes, le chemin qu'il emprunte à travers la savane africaine est en réalité vécu consciemment, et cela l'amène à rencontrer une constellation d'animaux divers, dont le trait commun est le choix de la liberté comme bien le plus valorisé. C'est une réussite d'avoir une littérature aux idées critiques comme celles qui apparaissent dans ce livre qui, sans perdre la beauté de son écriture, offre à ses lecteurs la possibilité de se demander s'ils doivent vraiment paître dans les prés éternels de la coutume. C'est une histoire réservée aux grandes personnes, quel que soit leur âge, qui invite à la conviction que le « grand chemin » est celui qui nous guide vers le cœur même d'une vie solidaire et authentique.

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE)~Luisa Capetillo: escalando la tribuna

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE)~Luisa Capetillo: escalando la tribuna

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), a small-scale independent publisher, established in 2009 in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, is proud to announce the release of its most recent titles to the Caribbean’s ample and diverse public.

As part of our Libros Libres series, we offer the open access book Luisa Capetillo: escalando la tribuna, a bilingual, annotated edition of the Puerto Rican anarchist and feminist Luisa Capetillo’s texts Ensayos libertarios and La humanidad en el futuro. The book’s editor is Nancy Bird-Soto, while Amy Olen is the translator into English. As the introductory essay notes, in said texts Capetillo shows the fundamental axes of her emancipatory thought and imagination in registers that oscillate between the courageous public discourse based on the streets, and the utopic aspirational call for better horizons. With this publication, we broaden the access to Capetillo’s work both in the Puerto Rican archipelago and its diasporas. Likewise, we offer a valuable educational text – annotated and with a section of questions for analysis – for an urgent, emancipatory education.

Nuevos títulos de Editora Educación Emergente (EEE)~

Luisa Capetillo: escalando la tribuna

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), proyecto editorial independiente de pequeña escala, fundado en 2009 y con base en Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, presenta al amplio y diverso público caribeño sus seis títulos más recientes.

Por su parte, ofrecemos en formato digital de acceso libre, como parte de nuestra serie Libros Libres, el título Luisa Capetillo: escalando la tribuna, que consiste en una edición comentada y bilingüe de Ensayos libertarios y La humanidad en el futuro, textos de la anarquista y feminista puertorriqueña Luisa Capetillo. El libro cuenta con el cuidado editorial de Nancy Bird-Soto y la traducción al inglés de Amy Olen. Como bien señala el ensayo introductorio, en dichos textos Capetillo plantea los ejes fundamentales de su ideario emancipador en registros que oscilan entre el discurso aguerrido anclado en la calle y la aspiración utópica que imagina mejores horizontes. Con esta publicación, multiplicamos el acceso al pensamiento de Capetillo tanto en el archipiélago boricua como en sus diásporas. Al mismo tiempo, ofrecemos un texto escolar valioso – anotado y con una sección de preguntas de análisis – para una educación liberadora impostergable.

Nouveaux titres d’Editora Educación Emergente (EEE) / Éditrice Éducation Émergente (EEE) ~ Luisa Capetillo : escalando la tribuna (Luisa Capetillo : monte la tribune)

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), projet d’édition indépendant à petite échelle, fondé en 2009 et basé à Cabo Rojo, Porto Rico, présente ses six titres les plus récents à l’ample et divers public caribéen.

De son côté, nous proposons en format numérique en libre accès, dans le cadre de notre série Libros Libres (Livres Libres), le titre Luisa Capetillo : escalando la tribuna ( Luisa Capetillo : monte la tribune ), qui consiste en une édition commentée et bilingue d'Essais libertaires et L'Humanité dans le futur, textes de l'anarchiste et féministe portoricaine Luisa Capetillo. Le livre est édité par Nancy Bird-Soto et traduit en anglais par Amy Olen. Comme le souligne l'essai introductif, Capetillo soulève dans ces textes les axes fondamentaux de son idéologie émancipatrice dans des registres qui oscillent entre le discours aguerri ancré dans la rue et l'aspiration utopique qui imagine des horizons meilleurs. Avec cette publication, nous multiplions l'accès à la pensée de Capetillo tant dans l'archipel portoricain que dans ses diasporas. En même temps, nous offrons un précieux texte scolaire – annoté et avec une section de questions d'analyse – pour une éducation libératrice qui ne peut être différée.

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE)~Deudas coloniales: el caso de Puerto Rico

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE)~Deudas coloniales: el caso de Puerto Rico

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), a small-scale independent publisher, established in 2009 in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, is proud to announce the release of its most recent titles to the Caribbean’s ample and diverse public.

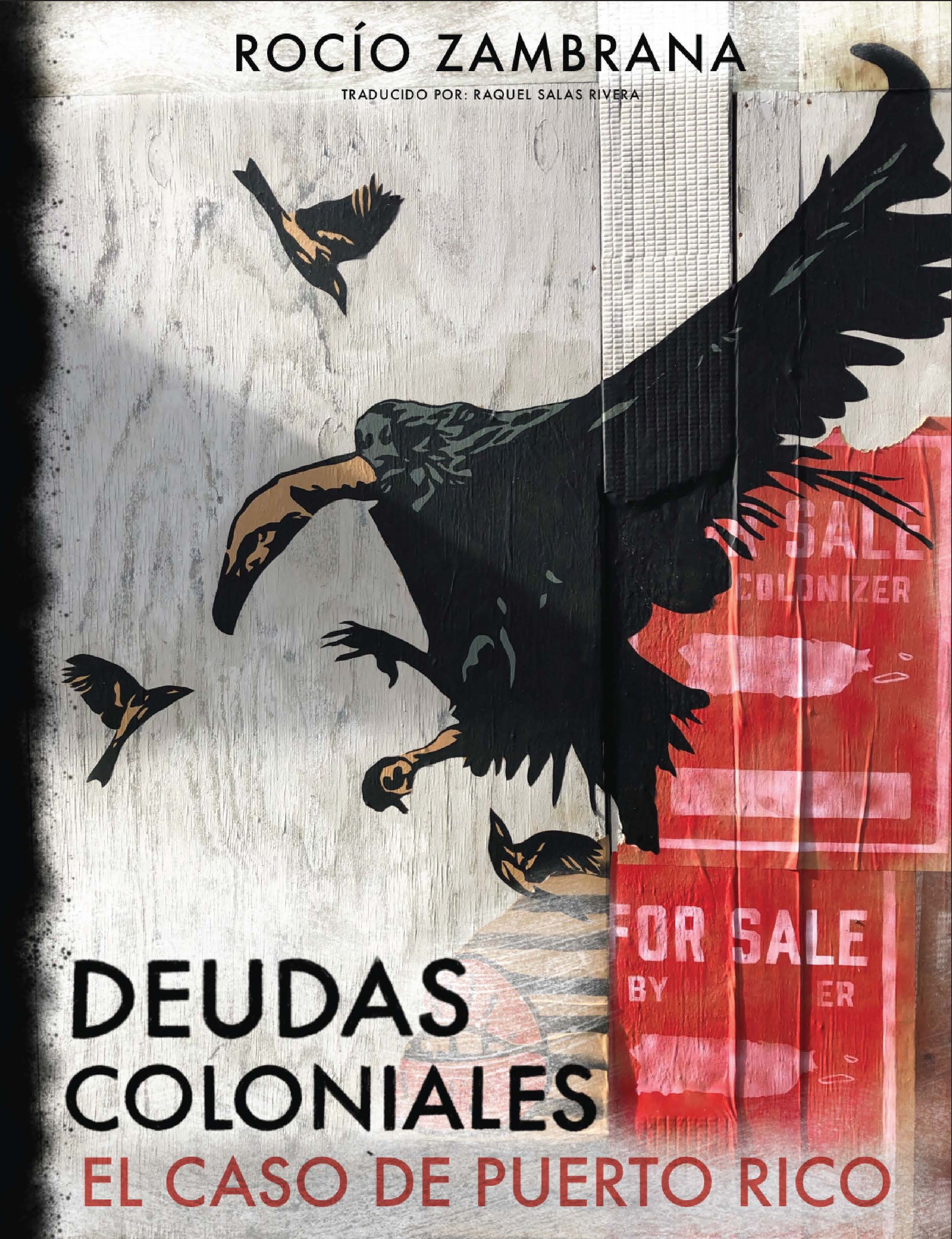

Our Otra Universidad series now includes Deudas coloniales: el caso de Puerto Rico by Rocío Zambrana (translated into Spanish by Raquel Salas Rivera and illustrated by Bemba PR). In this book, which is also available in our open access digital platform, Zambrana offers a robust conversation with thinkers, creators, and activists in Puerto Rico and the Global South, as well as with some of the most well-known observers in the European and North American contexts, on debt as a form and practice of capture, subjection, control, and dispossession that deepens and expands capitalist colonial modernity’s reach. At the same time, Puerto Rico’s particular case shows that, to achieve this, capitalism requires constant “updating” of the colonial condition as a racist order, and not only as a juridico-political form of subordination, within “altered material and historical conditions.” Financial debt in the colony, thus, is a “manifestation of historical debt” –that of conquest and enslavement–, operating as an agent of the race/gender/class regimen that the “coloniality of power” (the concept is Aníbal Quijano’s) perpetuates in the present by means of new rounds of invasion, plunder, and exploitation. However, Puerto Rico also exemplifies, Zambrana argues, hopeful forms of “organizing pessimism,” which can be noticed in various practices of resistance, such as refusal, subversion, and rescue/occupation. These interrupt the subjection of financial and historical debt, despite the inherent challenges of neoliberal cooptation. Even with gestures that appear inconsequential or temporary, our resistances constitute decolonial and reparative modes of “life binding.”

Nuevos títulos de Editora Educación Emergente (EEE)~Deudas coloniales: el caso de Puerto Rico

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), proyecto editorial independiente de pequeña escala, fundado en 2009 y con base en Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, presenta al amplio y diverso público caribeño sus seis títulos más recientes.

La serie Otra Universidad se robustece con Deudas coloniales: el caso de Puerto Rico de Rocío Zambrana (traducción al español de Raquel Salas Rivera). En este libro, también disponible en nuestra plataforma en formato digital de acceso libre, Zambrana ofrece una robusta conversación con pensadorxs, creadorxs y activistas de Puerto Rico y el Sur Global, así como con algunxs de lxs observadorxs más conocidxs en el contexto europeo y norteamericano, en torno a la deuda como forma y práctica de captura, sujeción, control y desposesión que profundiza y expande el alcance de la modernidad capitalista colonial. Al mismo tiempo, el caso particular de Puerto Rico demuestra que, para lograr lo anterior, el capitalismo requiere la continua “actualización” de la condición colonial como orden racista, no sólo como subordinación jurídico-política, en “condiciones materiales e históricas alteradas.” La deuda financiera en la colonia, entonces, es una “manifestación de la deuda histórica” de la conquista y la esclavitud, fungiendo así como agente del régimen de raza/género/clase que “la colonialidad del poder” (el concepto es de Aníbal Quijano) perpetúa en el presente a través de nuevas rondas de invasión, saqueo y explotación. No obstante, Puerto Rico también ejemplifica, plantea la autora, formas esperanzadoras de “organizar el pesimismo,” que pueden advertirse en variadas prácticas de resistencia, tales como el rehusarse, la subversión y el rescate/ocupación. Éstas interrumpen la sujeción de la deuda, tanto financiera como histórica, pese a los inherentes desafíos de la cooptación neoliberal. Así sea con gestos que parecen inconsecuentes o temporeros, nuestras resistencias constituyen modos descoloniales y reparadores de “vincular la vida.”

Nouveaux titres d’Editora Educación Emergente (EEE) / Éditrice Éducation Émergente (EEE)~Deudas colonialas : el caso de Puerto Rico

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), projet d’édition indépendant à petite échelle, fondé en 2009 et basé à Cabo Rojo, Porto Rico, présente ses six titres les plus récents à l’ample et divers public caribéen.

La série Otra Universidad (Une autre université) se renforce avec Deudas colonialas : el caso de Puerto Rico ( Dettes coloniales : le cas de Porto Rico ) de Rocío Zambrana (traduction en espagnol de Raquel Salas Rivera). Dans ce livre, également disponible sur notre plateforme dans un format numérique librement accessible, Zambrana propose une conversation solide avec des penseurs/euses, des créateurs/trices et des militants/militantes de Porto Rico et du Sud, ainsi qu'avec certains des observateurs/trices les plus connus/ues dans le contexte des pays européens et nord-américain, autour de la dette comme forme et pratique de capture, d'assujettissement, de contrôle et de dépossession qui approfondit et élargit la portée de la modernité capitaliste coloniale. En même temps, le cas particulier de Porto Rico démontre que, pour atteindre ceci, le capitalisme exige la "mise à jour" continue de la condition coloniale en tant qu'ordre raciste, non seulement en tant que subordination juridico-politique, dans des "conditions matérielles et historiques altérées. » La dette financière dans la colonie est donc une "manifestation de la dette historique" de la conquête et de l’esclavage, agissant ainsi comme un agent du régime de race/genre/classe que "la colonialité du pouvoir" (concept d'Aníbal Quijano) se perpétue dans le présent à travers de nouvelles séries d'invasions, de pillages et d'exploitations. Cependant, Porto Rico illustre également, selon l'auteur, des manières pleines d'espoir d’« organiser le pessimisme », qui peuvent être observées dans diverses pratiques de résistance, telles que le refus, la subversion et le sauvetage/l'occupation. Ces manières brisent la sujétion de la dette, à la fois financière et historique, malgré les défis inhérents à la cooptation néolibérale. Que ce soit par des gestes qui semblent anodins ou temporaires, nos résistances constituent des manières décoloniales et réparatrices de « relier la vie ».

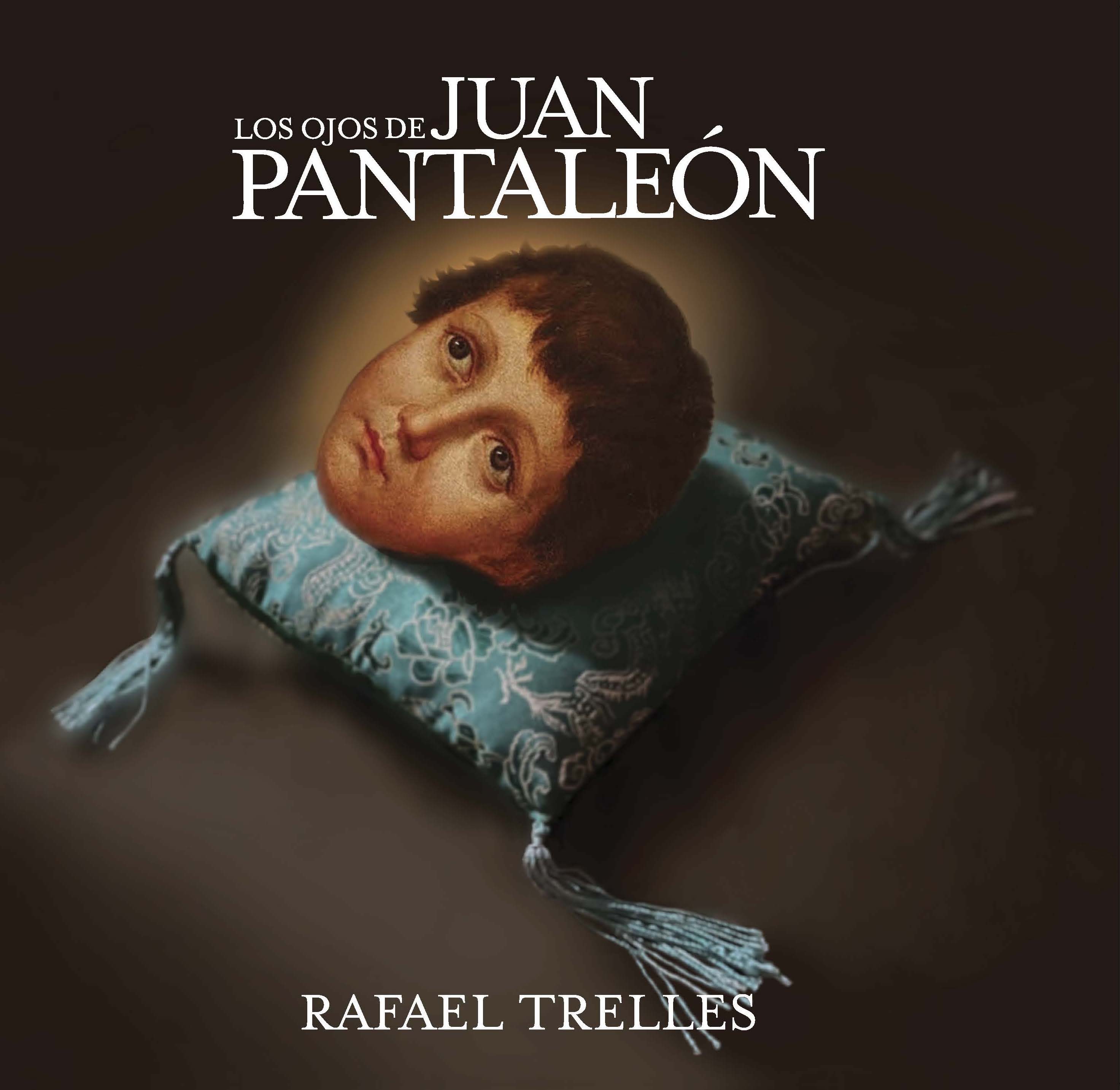

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE)~Los ojos de Juan Pantaleón

New Titles from Editora Educación Emergente (EEE)~Los ojos de Juan Pantaleón

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), a small-scale independent publisher, established in 2009 in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, is proud to announce the release of its most recent titles to the Caribbean’s ample and diverse public.

The illustrated story Los ojos de Juan Pantaleón by Puerto Rican artist Rafael Trelles was published as part of our Edades de Siddhartha series. Of the book, the writer Vanessa Vilches Norat notes: “Juan Pantaleón Avilés de Luna Alvarado, the Avilés Boy, holds a privileged place in Puerto Rico’s teratology. As a metaphor for a country impeded of full development, it has been elaborated in the archipelago’s graphic and narrative arts since the great 1808 painting by Campeche. Rafael Trelles revisits the story of the boy who is all eyes to question and illustrate –quite literally– our present as an invaded, plundered and auctioned territory. Here, the crippled infant’s gaze is, in addition to beautiful, inquisitive. As though Trelles’ masterful hand was split between graph and trace, Los ojos de Juan Pantaleón is a delicate blink between the artist’s story and illustrations.”

Nuevos títulos de Editora Educación Emergente (EEE)~Los ojos de Juan Pantaleón

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), proyecto editorial independiente de pequeña escala, fundado en 2009 y con base en Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, presenta al amplio y diverso público caribeño sus seis títulos más recientes.

En la serie Edades de Siddhartha, aparece el relato ilustrado Los ojos de Juan Pantaleón, del artista puertorriqueño Rafael Trelles. A propósito de este libro, señala la escritora Vanessa Vilches Norat: “Juan Pantaleón Avilés de Luna Alvarado, el Niño Avilés, tiene un lugar privilegiado en la teratología puertorriqueña. Metáfora de un Puerto Rico impedido para el pleno desarrollo, ha sido elaborado en la gráfica y en la narrativa desde el magnífico retrato que Campeche pintó en 1808. Rafael Trelles revisita la historia de ese niño todo ojos para cuestionar e ilustrar –nunca mejor dicho– nuestro presente de territorio invadido, espoleado y subastado. Aquí, la mirada del infante tullido es, además de hermosa, inquisidora. Como si la maestría de la mano de Trelles se desdoblase en grafo y trazo, Los ojos de Juan Pantaleón es un delicado parpadeo entre el cuento y las ilustraciones del artista.”

Nouveaux titres d’Editora Educación Emergente (EEE) / Éditrice Éducation Émergente (EEE)

Editora Educación Emergente (EEE), projet d’édition indépendant à petite échelle, fondé en 2009 et basé à Cabo Rojo, Porto Rico, présente ses six titres les plus récents à l’ample et divers public caribéen.

Dans la série Edades de Siddhartha (Les âges de Siddhârta), apparaît l'histoire illustrée Los ojos de Juan Pantaleón ( Les yeux de Juan Pantaleón ), de l'artiste portoricain Rafael Trelles. À propos de ce livre, l'écrivaine Vanessa Vilches Norat précise : Juan Pantaleón Avilés de Luna Alvarado, l'Enfant Avilés, a une place privilégiée dans la tératologie portoricaine. Métaphore d'un Porto Rico empêché de s'épanouir pleinement, elle s'élabore graphiquement et narrativement depuis le magnifique portrait que Campeche a peint en 1808. Rafael Trelles revisite l'histoire de cet enfant aux yeux écarquillés pour interroger et illustrer -jeu de mots- l’actualité de notre territoire envahi, éperonné et vendu aux enchères. Ici, le regard de l'enfant infirme est aussi beau que curieux. Comme si la maîtrise de la main de Trelles se déployait en graphique et en ligne, Les yeux de Juan Pantaleón est un délicat scintillement entre le conte et les illustrations de l'artiste.

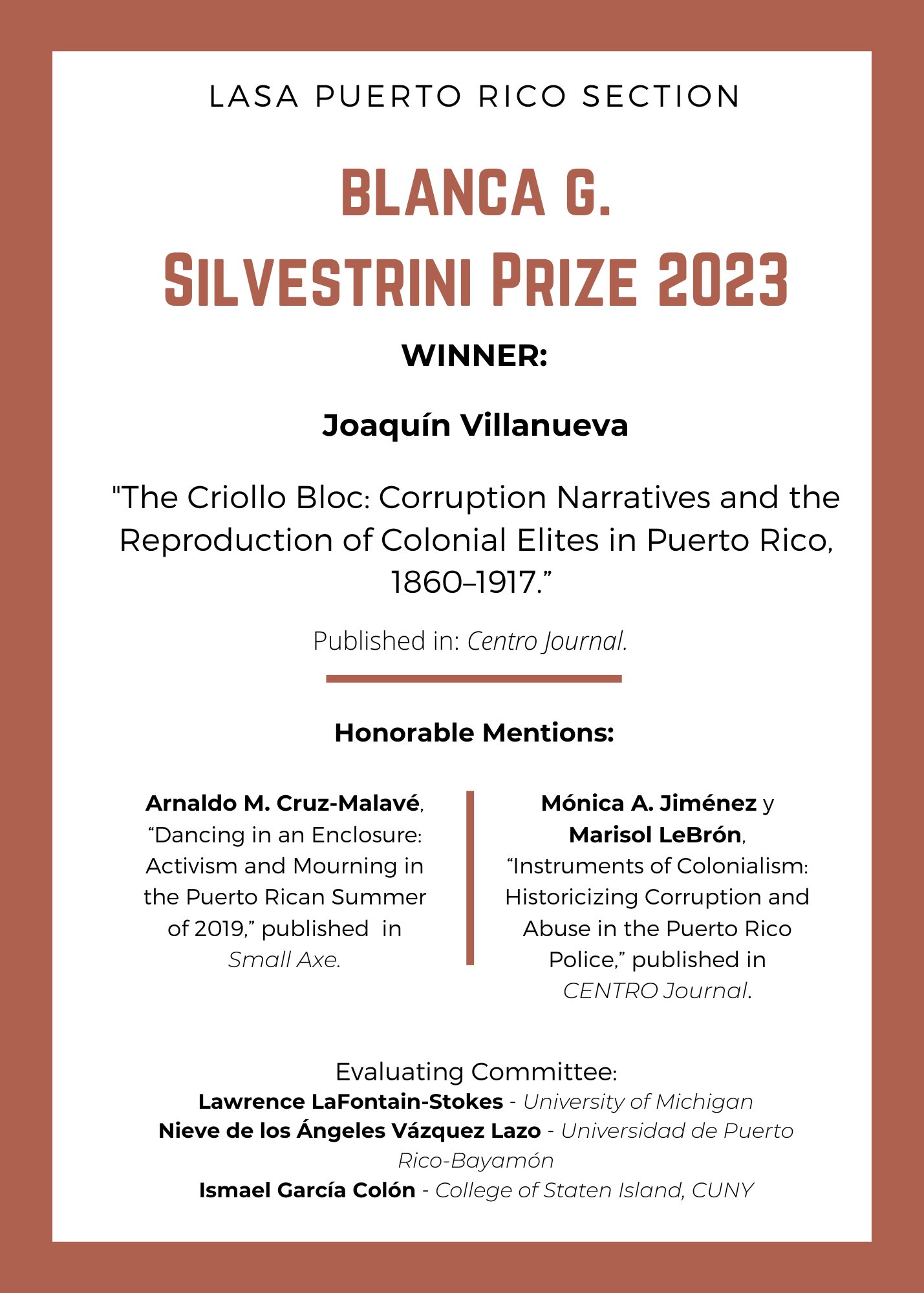

Congratulations to Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé and the Honorable Mention of his SX Essay

Congratulations to Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé and the Honorable Mention of his SX Essay

Congratulations to winners of the 2023 Bianca G. Silvestrini Prize and congratulations to Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé for having his essay in Small Axe 68 selected as honorable mention!

Below you will find the abstract for this essay "Dancing in an Enclosure: Activism and Mourning in the Puerto Rican Summer of 2019," which you can read here.

An examination of the significance of dance performances in the demonstrations of the Puerto Rican summer of 2019, this essay argues that these performances belong to a history of irreverent, extravagant mourning gestures that periodically irrupt in Puerto Rican culture as decolonial practices by dislocating the socially prescribed binding between performance and affect. Using the theories of Saidiya Hartman, José Esteban Muñoz, and Juana María Rodríguez, and connecting to the work of Rocío Zambrana on strategies that address the island’s colonial legacy, the essay explores the mournfully irreverent dance performances of the Afro-Boricua bomba dancer Clara Isabel Díaz, the patería combativa (combative queer voguing) of Aldrin Manuel Cañals, and the reggaetón perreo of queer feminist activists Perra Mística and Kaya Té as gestures of loss and mourning that both demand redress and enact what Puerto Rican artists, activists, and critics have begun to call “decolonial joy.”

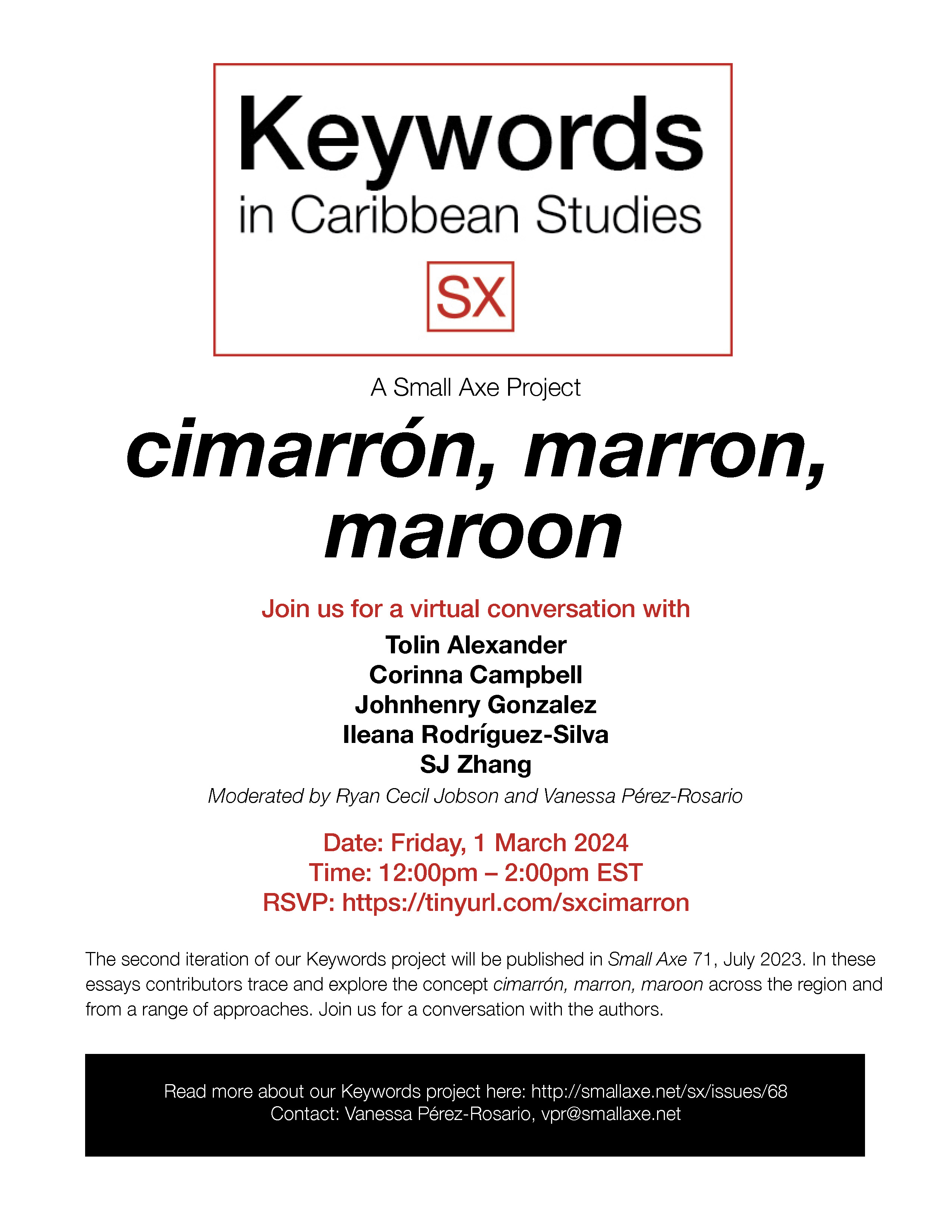

Register for Keywords in Caribbean Studies Conversation

cimarrón, marron, maroon

Register for Keywords in Caribbean Studies Conversation

cimarrón, marron, maroon

You can RSVP for the event here here.

The second iteration of our Keywords project will be published in Small Axe 71, July 2023. in these essays contributors trace and explore the concept of cimarrón, marron, maroon across the region and from a range of approaches. Join us for a conversation with the authors.

Read more about our keywords project here: http://smallaxe.net/sx/issues/68

Contact: Vanessa Pérez-Rosario, vpr@smallaxe.net