sx art

sx art is the Small Axe Project platform devoted to visual practice and its place in Caribbean cultural, social, and political life. Since its inception, our print journal Small Axe, has been concerned to explore ways in which visual practice, and more generally Caribbean visual culture, has been at the center of the experimental cultural, political, and aesthetic imagination of the region and the diaspora. The journal has consistently featured the work of artists on its covers, developing a distinctive style and sensibility and focus. During this period, also, reflecting our recognition of the increasing importance of visual arts to the self-consciousness of Caribbean critical practices, Small Axe has published visual art portfolios that engage in greater depth the work of contemporary and emerging artists. sx art aims to expand this work, presenting visual culture across a range of genres and forms: from photography to the moving image, from performance to architecture, from soundscapes to painting and sculpture. We aim to create a significant body of visual material with a scope and breadth that contributes and compliments what has gone before. In our view, it is through further discussion and questioning of visual material created by and about the Caribbean, that more progressive insights and meanings may be gained. sx art will unveil a new visual arts-focused feature every January, May and September.

Curatorial Director

Andil Gosine

andil@yorku.ca

artist / project

sx art 8

sx art 7

sx art 6

sx art 5

sx art 4

sx art 3

sx art 2

sx art 1

sx art 8

-Deborah Anzinger

Training Station and Untitled Transmutations, or How Not to Die

I have been thinking about Deborah Anzinger’s practice for over a decade. Though she is probably best known as a painter, I have always thought of her practice as much more. I think of hers as a kind of social practice that self-consciously operates on multiple levels (intimate, professional, formal, material, international, local). The practice seems to me an ethos, or maybe an ethic, that manifests itself in her studio practice and its outputs, but also in her leadership of New Local Space (NLS), as well as other aspects of her personal and professional lives.[1] In her recent projects Training Station (2020 - present) and Untitled Transmutations (2022 - present), this aspect of her work is foregrounded, with material and formal developments reflecting relational and political commitments in new and compelling ways. There is also a renegotiation of normative conceptions of authorship, collaboration, community and ownership emerging that has particular currency in this fraught moment. The following interview is an attempt to tease out these themes and recontextualize a practice that is evolving in exciting ways.—Nicole Smythe-Johnson

[1] NLS (or New Local Space) is an artist-run contemporary visual art initiative in Kingston, founded by Anzinger in 2012. See nlskingston.org for details of their programs.

NSJ: Can you describe the Training Station project? Its parts and how it has evolved?

DCA: Training Station is a land-based work on my family land in Maroon Town, St. James in Jamaica. The central focus of the work is afforestation — tree planting of native trees. All of this happens around a mud structure that we created as part of the project. The mud structure involved us, as community members in Maroon Town, doing some research to try and reclaim lost technical knowledge and apply it to building a space. The space has evolved into a place for sharing some of the techniques that went into the building of the structure. We’re also transferring knowledge we gathered beyond Maroon Town, to the various communities that I have touch points with, including artists in Kingston and further afield. It also has become a site of encounter, a site of connection between the community in Kingston and the community in Maroon Town and a site for trying to discuss and understand what is possible, or what could be possible if we shift perspectives on what we consider valuable. This land has been with our family for generations.

NSJ: You mention lost technical knowledge, what kinds of knowledge are we talking about? And what was your process for recovering these techniques? I’m also curious about your collaborators. I know several members of your family are involved, and others who live and work in Maroon Town. Who are the key figures and what are their roles?

DCA: Training Station was about reorienting our understanding of making space. How could we make space architecturally, physical space, while also thinking about the Earth and thinking about our place within the Earth. Why do we even need space and what are we going to do with that space?

We didn't really know how to reconnect with traditional building techniques. What we had was a crew of people, tradespeople in masonry who were now without work because we were in curfew, during the pandemic. No one could work in their trade. We had access to the internet and unclear passed down, second hand, third hand information about how you could make an earthen structure. Somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody who said you could do it this way.

We had time and we had funds. I had just received the Soros Arts Fellowship from the Open Societies Foundation. That money went towards paying the group of people I was working with to experiment and see what worked. Everyone had their fair share of self-doubt and scepticism about whether we had what it took to make this work, materially or technically, but having that time to experiment meant we had no escape from our fear and doubt. We couldn't make the excuse of “not enough time,” or “not enough money” because we had the money to pay for our time. No one had to worry about the necessities of life.

I did some research on the internet, good ole YouTube University. And then the other team members were also doing research on the internet. At that point it was Evil [Warren Welch]—a distant relative of mine, Scissors [Ricardo Gordon], Teno [Trevelen], and Tash [Leasie Duhaney] who were working on the project. We were seeing the same things over and over, but they couldn't tell you about what soil you actually had on hand. After a while, Evil started telling me that he was having dreams about it. He had a dream about how he was supposed to mix the materials, and how we were to make the blocks. He was familiar with making cement blocks, so he used some of that technique to make the earthen blocks. Then he had a dream about which grasses to use and how much grass was supposed to go in each, and we went from there. So, it was a combination of very unclear passed down information, internet research, and dreams that we were having. We tried them out and it worked. There were other people who were part of the team too. Jefud [Owen Brooks] helped. There’s a long list of people who passed in and out, but the main people from start to finish were Evil, Scissors, Tash, Teno, Jefud, Jamesie [Wright] and Jagan [Charles Nugent].

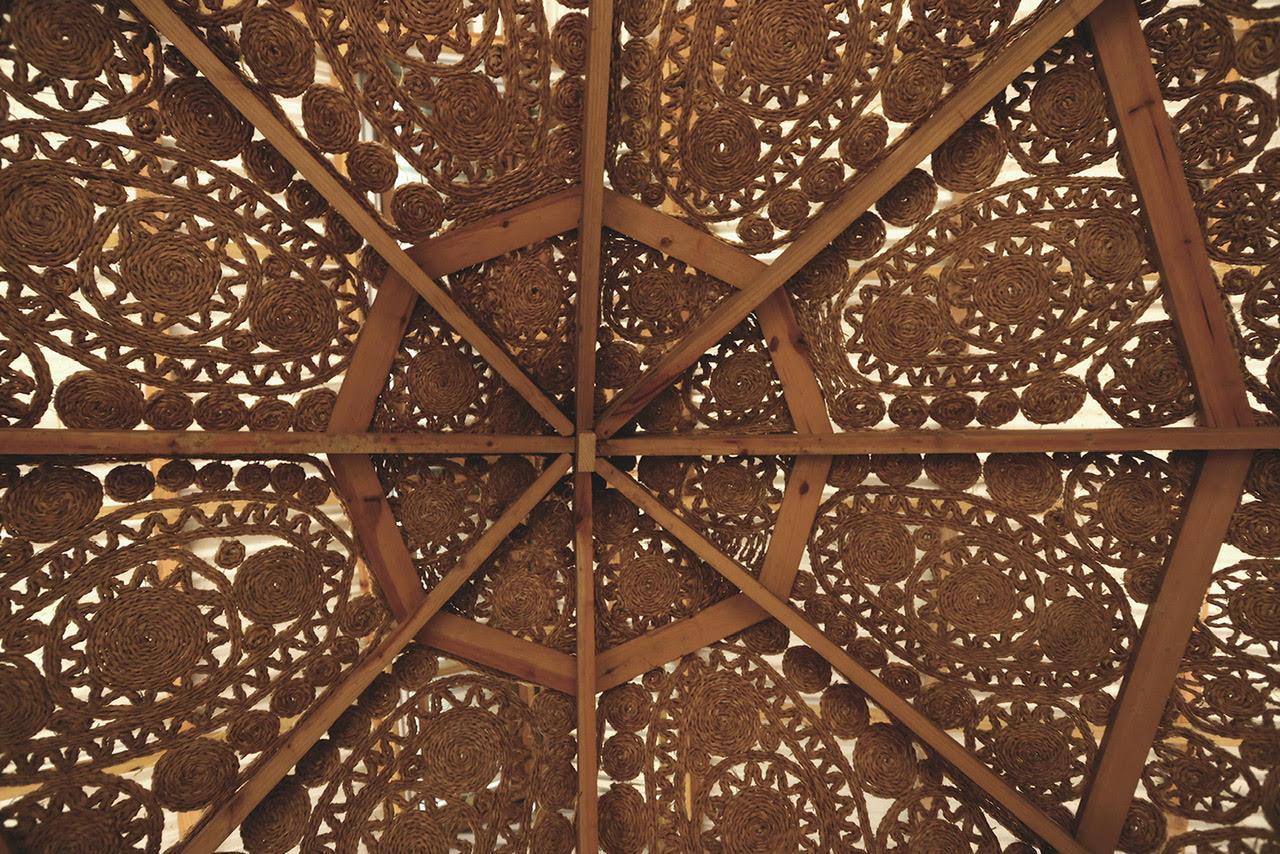

Then once the earthen structure was completed, Keen [Coke] came in and started working on a ceiling, which is that woven structure at the top. When you look up, a lot of people say it gives a cathedral feeling, because the light is coming through the woven ceiling. It's really very beautiful. Keen harvested the grass on the same land. And dried it, braided it, and made this design with me. Then he executed the actual weaving.

Eventually we used the space as a workshop. I learned to weave from Keen in that space. Keen has taught several people how to weave there: kids in Maroon Town, visitors from Philadelphia, artists in residence from Kingston. It's a meeting point, and it's a point of transferral and exchange, because in all of that process Keen rebuilt a lot of confidence and faith in his practice. He was known as someone who could weave, but he was not actively practicing. He only resumed once we started this project. When was that? 2020? And now we're going into 2026, and Keen is still weaving, and we've gone on to have the Sustainable Art Summer Camp through NLS. Keen, who had been asking me to find him students, had quite a few enthusiastic students across a range of ages. So, it's also a process of building confidence, of building our own confidence in viability, in the things that are coming from our hands, the things that are coming from the earth, and ways we can work in alignment with the earth.

NSJ: I also want to ask you about audience. Something notable about this project is that you’ve been very protective of the space, who can access it and how. Can you tell me about your philosophy on this and what motivated those choices?

DCA: Well, culture is a process within a community, so if one has an audience… audience suggests a spectator, not a participant. And if we are in the work of building culture, building confidence in ourselves, that’s not the business of performing for an audience. Those are two different businesses, and this project is about culture. Culture is a focus of this work. I think the question of audience and being protective of this work from audiences is not even really much of a consideration. Once one’s focus is on community and culture, the idea of an audience just fades away. And this is not to say that the community cannot extend beyond Maroon Town and that the community cannot extend beyond the people who directly built the space. It just means that those who are experiencing the work are also those who are participating in the work.

NSJ: How do the charcoal paintings fit into this? Can you talk about the development of those works? Do you consider them a part of the Training Station project? I guess another way to think about this question is, what role does capital-A-art have in all this?

DCA: The charcoal paintings follow a similar timeline to Training Station. They were also developed during lockdown. We were in a context where trade and movement across borders was shut down, and I was able to focus on some of the essential questions of the work that I did between 2016 and 2019 regarding the connection of economy to land. The lockdown opened the time and space to really look at the materiality of the work… aligning with and embodying the ideas within the work. I was looking at the economy of the materials I was using, and how that was related to the space in which I was existing and living.

At first, the experiment started with the clay in the land where Training Station existed. That was an interesting process, because you really start to think about the irreplaceability of the materials that you're using, the irreplaceability of clay. Training Station involves planting trees. In using clay to make the work, I'm actually taking some of the source for these living plants to create these images that are reflective of my experience in this space…and the economy of that. That's not the way I wanted the work to function.

I then started using charcoal…experimenting with local charcoal that we generally use to cook when we don't have access to gas or electricity in Jamaica. It's a common fuel source that is accessible. The relationship of that fuel source to the forest is very tense, but it's also a relationship that we can engage in a conscious and cyclic way. I'm able to plant trees and in the creation of these images and these artworks, I can support afforestation through sale of those artworks. You also start to think about how much of the material you're using and how much of the material you're planting back. You start to think about how much you’re putting in versus how much you're taking. The Untitled Transmutation charcoal paintings embody that kind of tense relationship. I am using so little of that material in a sort of residual way to make these paintings. The paintings are also coming from the residue that being in the space has imprinted on my mind and on my spiritual existence.

Then about two years into making these works and working within Training Station, we experienced a wildfire that really devastated a lot of the trees we planted. We had planted hundreds of trees. We planted cashew, nutmeg, pimento, mahogany, cedar, blue mahoe, avocado… and the fire devastated them all in a matter of hours. During the sorrow of going through and assessing the destruction, I started picking up the burnt bamboo that was all over. I should say that bamboo is a species that we really had to contend with when we were doing the afforestation because it's an invasive species. It's one of these species that is the first to grow back whenever there is a drought and it spreads really fast and creates an environment that is very difficult for the native trees to grow back in. So, there was all this burned bamboo all over the place and I started picking it up. Because I had been experimenting with charcoal before, I saw the charcoal in a way that I don't think I would have seen it otherwise. Working with the charcoal became a way of processing the grief of the loss.

As I was making these images, I was also thinking “what next?” We were still going to have to plant back whether or not devastation would happen again. Just giving up wouldn't be an option. About a month into working in the studio and processing, we were looking through again and Jeffud said to me: "Look at this. Tell me what you see.” And on one of the cashew trees that looked like it had been burnt to a crisp there was a bud coming out. That's when we came to realise that a lot of the trees weren’t actually dead. They looked like they were dead, but there was still life. It's because the root system of some of them had matured enough that they could spring back. The forest fire was in 2023 or 2024, it's hard to keep track. Anyway, I would say about 80% of the trees sprung back. Right now, I'm still making work from that bamboo charcoal that we harvested from the forest fire. It also made me think more about so-called invasive species and our relationship to them. The bamboo is a more sustainable source of the charcoal. It is something that we could be using instead of some of the other species that are typically used for charcoal.

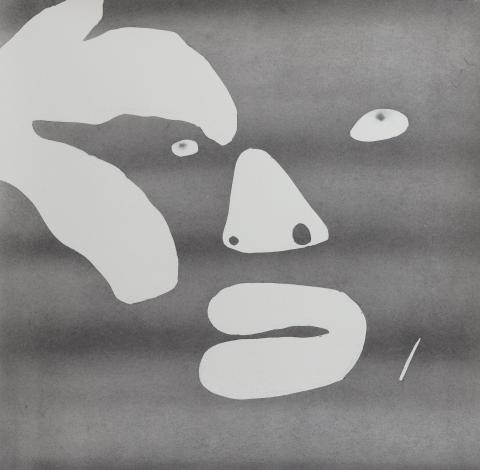

The imagery in Untitled Transmutations is ethereal. Often there's a play between negative and positive space. I'm moving the pigment on the paper with dry and wet techniques. There's a dynamic between these gradients, ethereal spaces, and these other spaces that are more wet and turbulent. I try not to overplan them. I make a lot of studies, but I try to give a lot of space and air to them, so that whatever wants to present itself on the paper can present itself and it's often images of impressions. Trees and beings who don't quite take a full body figuration. I leave the impression of a figure or a person. The figure is dissipating into the space. They're discernible, but not discreet, there's a play between abstraction and embodiment; a shift between the ethereal and the texture; between the physical and an unknowingness. I'm developing a confidence in whoever steps into the work and engages the work… a confidence in the unknowingness of space and the unknowingness of being, a certain familiarity with unknowingness…a comfort in the unfolding that this work encourages.

Post Script

Hurricane Melissa, the first documented Category 5 to make landfall in the Atlantic Basin, hit southwestern Jamaica on October 28, 2025. This was in the middle of our discussions. The following are lightly edited excerpts from Whatsappconversations between us, immediately before, during and after the storm hit.

[5:48 AM, 10/28/2025] NSJ: How tings? Still online?

[8:34 AM, 10/28/2025] NSJ: Looks like Maroon Town will get a big hit.

[9:54 AM, 10/28/2025] DCA: Bad cell phone service. WiFi down. We are ok. Was scary at about 3 - 5 am.

[9:55 AM, 10/28/2025] DCA: Maroon Town should be ok because of cockpits.[1]

[8:37 AM, 10/29/2025] DCA: Last night was the scariest part. Could not sleep. We are all ok.

[4:42 PM, 10/31/2025] DCA: Updates on Maroon Town. Still can’t get through to anyone there. Trying to get there tomorrow.

[9:00 AM, 11/2/2025], DCA: Good morning. This is Maroon Town. The basic school is totally destroyed and there are people living in the church and the community center. [redacted] and her family will be living in the residency house for a time, though the roof of the Carroll house is also partially gone. All the trees are gone, the place is unrecognisable. The birds are starving, there is nowhere for them to live and nothing for them to eat. People’s spirits are indomitable and everyone was working trying to get things patched up. The relief delivered was greatly appreciated as no one has heard anything from government re: relief and they are totally cut off. No cell phone service and no light. Roads are blocked off, we got an alternate route from the council member.[2]

[9:00 AM, 11/2/2025] DCA: there is also a gas crisis in St. James and extremely long lines go down the highway, people parked and looking for gas. We witnessed a fight at the gas station as we were passing. They had JCF [Jamaica Constabulary Force] come out to all the gas stations including the one right down there by Flankers.

[1:58 PM, 11/15/2025] DCA: We went up from Maroon Town to Flagstaff yesterday.

The seeds and trays were incredibly appreciated. We went to two locations, word spread farmers met us and asked if we had anymore and we did not. I told them coming Saturday. It was a frenzy for the seeds.

We set up at the Flagstaff Community Center. We had to be mindful how we utilised the building as it was a shelter space as well and people are now dwelling there. So we distributed from the window.

[2:06 PM, 11/16/2025] DCA: The majestic Blue Mahoe, one of the trees we planted in partnership with the forestry department and stewarded from a sapling, is now down. But we see there are signs it can come back. We need to build capacity to set all the surviving trees upright.

[2:06 PM, 11/16/2025] DCA: The round mud house is still standing amid the devastation.

Nicole Smythe-Johnson is a writer and curator from Kingston, Jamaica. She is currently assistant professor of art history and African American and Black diaspora studies at Boston University.

[1] St. James Maroon Town is located in the Cockpit Country that spans parts of the parishes of St. James, St. Elizabeth and Trelawny in Jamaica. The community is approximately 29 kilometers southwest of Montego Bay, the capital of St. James. Cockpit Country is marked by lush forests, distinctive conical hills and steep-sided valleys and hollows, some as deep as 120 metres.

[2] Local government representative.