sx blog

Our digital space for brief commentary and reflection on cultural, political, and intellectual events. We feature supplementary materials that enhance the content of our multiple platforms.

Venezuela, the Caribbean, and Self-Determination

Venezuela, the Caribbean, and Self-Determination

The Small Axe Project team joins others in the United States and around the world in unequivocally condemning the U.S. abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores on January 3rd, 2026, and their forced transport to New York to stand trial on drug-related charges. We utterly condemn the murder of the 32 Cubans and nearly 50 Venezuelans this act of wanton state violence entailed. We condemn the flagrant U.S. breach of those articles of the United Nations charter that enshrine the rights of sovereignty: Article 2(1), protecting the sovereign equality of member-states; Article 2(4), prohibiting the use of force against the territorial integrity of member-states; and Article 2(7), protecting the right of non-interference in domestic affairs. We are alarmed that the U.S. administration has now issued threats against the sovereignty of Colombia and Cuba. It is a sad reflection of the supine posture of Caribbean states when the Conference of Heads of Government of CARICOM, which met later that morning, could rise no further than to meekly offer that the “situation is of grave concern” to the region. Where are our leaders?

Meet Our 2026 Editorial Assistants

We are happy to welcome Carlos and J who are joining our team as editorial assistants. And welcome back Dantaé and Laura, our returning assistants. We also thank our outgoing editorial assistant, Luis, for all of his intellectual and organizational contributions to the Small Axe Project.

Incoming Editorial Assistants

Carlos Montes Jiménez is a first-year PhD student in the Department of Anthropology at Columbia University. His research focuses on transnational networks of material and affective solidarity in the Caribbean, and how they articulate political imaginaries beyond the nation-state. Prior to moving to New York City, Carlos received a Fulbright Research Award to conduct research in Belém do Pará, Brazil. He is originally from Añasco, Puerto Rico, and holds a B.A. with distinction in Anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania, where he was a Mellon Mays Fellow. Carlos is passionate about dance, including genres like Brega, Samba de Gafieira, Bachata, and, above all, Salsa.

J Jokhai is a Master’s student at Columbia University in the Department of Anthropology. His research focuses on the relationship between oil and nationalism in Guyana, in the context of the country’s ascendant position in the world-system, its fraught socialist history, and its orientation towards U.S hegemony in the Caribbean. J is interested in political anthropology more broadly, as well as the anthropology of religion, art criticism with an emphasis on Modernist and contemporary art, and Marxism generally. He is honored to serve as a new editorial assistant for Small Axe. When not in class or writing for this journal, he is working to found Extant Magazine: Anthropology, whose first issue hopes to be published the summer of 2026. In his downtime, J is watching MMA, and reading a Manchette thriller on the F train in Queens, where he was born and raised.

Dantaé Garee Elliott, Ph.D., is a visiting lecturer at NYU’s Department of Spanish and Portuguese. Her work focuses on barrels (both as remittances and diasporic practices), the Caribbean diaspora, and contemporary art. Her dissertation, "Barrel Poetics", investigates barrel culture and its creative afterlives across Caribbean visual worlds. She has held diverse roles in academia and the arts, such as Co-Director of the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute Summer Seminar (Curatorial Fellowship class of 2022), Editorial Assistant at Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, and contributor to Forgotten Lands Art, Currents of Africa (Volume 04). She also served as a copy editor for Volume 05, The Haunted Tropics, and translator for Volume 07, Poetics of Architecture. A 2023 Mellon Fellow at NYU’s Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics, Elliott co-curated "Coral & Ash", the first solo exhibition of Vincentian photographer Nadia Huggins, at NYU’s KJCC. She was a 2024–2025 Doctoral Fellow at the Center for the Humanities and a Dean’s Dissertation Fellow at NYU, continuing her work at the intersection of Caribbean studies, visual culture, and critical imagination

Laura Berríos is a PhD student in the Department of Latin American and Iberian Cultures at Columbia University. Her research focuses on artistic and literary responses to disasters in the Caribbean. She holds a B.A. in Hispanic Studies from the University of Puerto Rico and is a returning Editorial Assistant who enjoys poetry, dancing, and being near the sea.

We thank Luis Frías and wish him the best of luck in his future endeavors.

Luis Frías is a New York-based scholar and writer pursuing a PhD in Latin American, Iberian, and Latino Cultures at the CUNY Graduate Center. Luis’s interests revolve around Mexican literature and cinema, archives, feminism, masculinities, violence, and neoliberalism. He splits his time between parenting his 5-year-old son, Leo, writing his dissertation, teaching Spanish and Portuguese languages, and wrapping up a book of tales. His current obsession is improving his times to run the NYC Marathon.

SX 78 is here!

SX 78 is here!

Small Axe 78 includes essays by Florian Gargaillo, John P. Sloan, Rachel Fulford, and Ryan Cecil Jobson. It features the special section "History as Repair: A Forum on Catherine Hall’s Lucky Valley," with essays by Jennifer L. Morgan, Vincent Brown, Robin D. G. Kelley, Walter Johnson, Sasha Turner, Kathleen Wilson, and Catherine Hall. The visualities section features Daniel Goudrouffe's work. Nathan H. Dize writes in the section Translating the Caribbean. The Book Discussion explores Malcom Ferdinand's Une écologie décoloniale: Penser l’écologie depuis le monde caribéen / Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World, with essays by Alex A. Moulton and Sophie Large.

The Small Axe Project Welcomes Simone Alexander

The Small Axe Project Welcomes Simone Alexander

With great pleasure, the Small Axe Project welcomes Simone A. James Alexander to the sx salon editorial team, taking over the role of Book Reviews Editor from Ronald Cummings. Simone is an eminent scholar of Caribbean and Black Diasporic literature with particular attention to the work of women writers; we are so grateful for the erudition, experience and commitment that she brings to this role. Her biography follows:

Simone A. James Alexander is Professor of English and Director of Africana Studies at Lehigh University. Her primary areas of research include women, gender, and sexuality studies; postcolonial literature; transnational feminist theory; Caribbean and migration and diaspora studies. She is the author of the award-winning monograph African Diasporic Women’s Narratives: Politics of Resistance, Survival and Citizenship, which also received Honorable Mention from the African Literature Association’s Book of the Year Scholarship Award. Alexander is also the author of Mother Imagery in the Novels of Afro-Caribbean Women and coeditor of Feminist and Critical Perspectives on Caribbean Mothering. Her scholarship has appeared in numerous journals and edited volumes, including Journal of West Indian Literature, L’Esprit Créateur, African American Review, Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies, Turkish Journal of Diaspora Studies, African Literature Today, Anglistica: An Interdisciplinary Journal, and MLA Approaches to Teaching Gaines: The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and Other Work (Modern Language Association). Her current book projects include Bodies of (In)Difference: Intimacy, Desirability and the Politics and “Poetics of Relation” and Black Freedom in (Communist) Russia: Great Expectations, Utopian Visions. She is also the editor of the forthcoming Cambridge Companion to Colson Whitehead. She serves on the editorial boards of Tulsa Studies in Women Literature, SAGE Publications, and Kosmos Publishers (Gender Studies and Equality).

Welcome Roque Raquel Salas Rivera, New sx salon Creative Editor

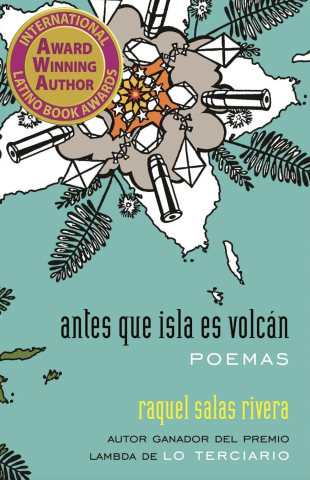

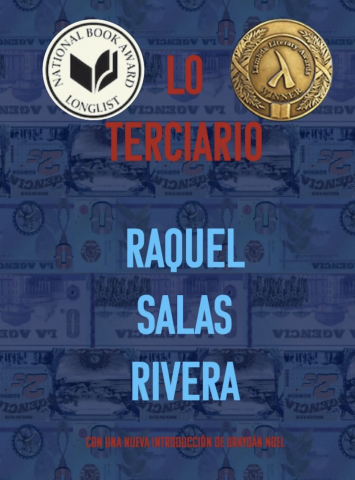

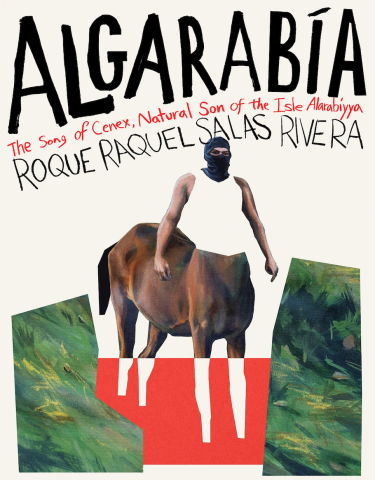

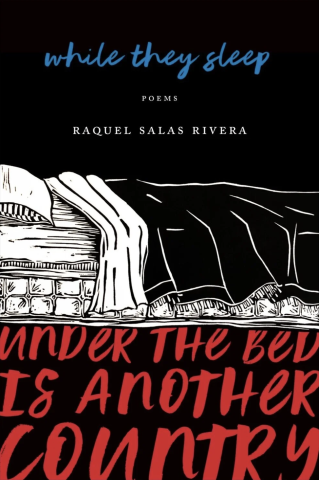

It is a great pleasure to add our welcome to Roque Raquel Salas Rivera, who joins the Small Axe Project as the incoming sx salon Creative Editor. Roque is a poet of alluring imagery and a translator of distinction, and it is a great privilege and honor to have him in our community in this capacity. Welcome Roque!

Roque Raquel Salas Rivera is a Puerto Rican poet, educator,and translator of trans experience.His honors include being named Poet Laureate of Philadelphia, the Premio Nuevas Voces, and the inaugural Ambroggio Prize. Among his six poetry books are lo terciario/ the tertiary (Noemi, 2019), longlisted for the National Book Award and winner of the Lambda Literary Award, and while they sleep (under the bed is another country) (Birds LLC, 2019), which inspired the title for no existe un mundo poshuracán at the Whitney Museum. In September 2025, Graywolf Press will publish his epic poem Algarabía. Roque currently teaches in the Comparative Literature Program at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, and serves the needs of a fierce cat named Pietri.

The Fragile Joy of Staying – If Only in Song: On Bad Bunny’s Residency

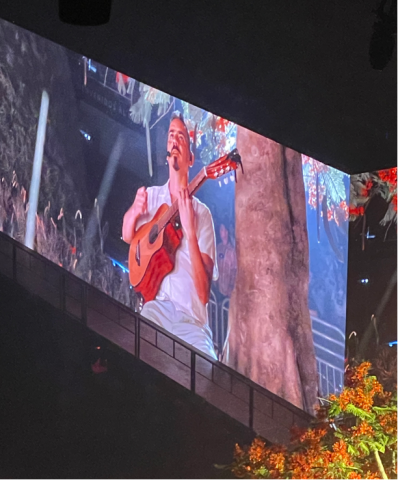

My seat neighbors, two best friends clinging to each other, voices breaking and tears streaming as they chanted every lyric of ‘Debí Tirar Más Fotos” (I Should Have Taken More Photos): their friendship louder than the song itself. Photo by the author. All rights reserved.

by Wilfredo José Burgos Matos

For weeks, millions worldwide queued online and in marathon lines for the event of the century: Bad Bunny’s residency at the Coliseo de Puerto Rico. Conceptually, this massive showcase placed Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricanness squarely at the center of global attention, reaffirming national identity and belonging. Simultaneously, it operated as an economic intervention, infusing the island with an influx of tourism, hotel and travel packages, and consumption that has transformed the concert into a temporary but significant driver of cultural and financial capital for locals.

Seeing the global impact it is having and knowing I might never be able to experience something like it again, I attended the tenth concert on Friday, August 1. On the day, I stepped into a sweltering golden San Juan afternoon where the heat clung to the skin and slowed the air. Inside, what unfolded was more than a concert. It was, as many called it, “an experience”: a reckoning with Puerto Rican memory, heartbreak, diaspora mourning, and the pursuit of joy amid gentrification, displacement, and the enduring weight of U.S. colonialism. Bad Bunny’s production traced the pulse of Puerto Rican popular music across time, weaving together tropes that revealed the textures of race, gender, and class identities, until the show itself breathed as a living archive.

The night opened with percussionist Julito Gastón leading an Afro–Puerto Rican batey de bomba, the communal space where rhythm, dance, and performance converge in Puerto Rican’s oldest musical form. Suddenly, reggaetón crashed into the barriles (bomba drums)in “ALAMBRE PúA” (Barbed Wire). Bad Bunny’s entrance alongside the drums staged a sonic dialogue between bomba and reggaetón, highlighting their intertwined histories.

As Petra Rivera-Rideau argues, reggaetón is rooted in Afro-diasporic traditions, though its Black origins are often obscured to appeal to white and middle-class sensibilities. Bad Bunny’s own racial positioning has sparked debate. Some call him jabao – a Caribbean term referring to light-skinned individuals with discernible African ancestry traits – while others stress his non-Blackness. The opening acknowledged this racial ambiguity. Rather than appropriating Afro–Puerto Rican expression, he staged an encounter, foregrounding entangled genealogies of sound and presenting them as complementary, not oppositional.

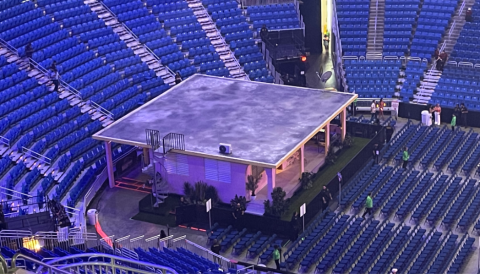

Sonic geographies are central to the residency. From the outset, the concert resisted reducing Puerto Rican Blackness to coastal imaginaries. Still with the barriles resounding, songs like “KETU TeCRÉ,” “EL CLúB,” “LA SANTA,” and “PIToRRO DE COCO” unfolded on a hilltop stage adorned with flamboyanes, plantain trees, a highway billboard, and a Puerto Rican cuatro player, his strings unfurling defiantly into the night. The cuatro, Puerto Rico’s national instrument, is distinguished by its ten paired steel strings and violin-like shape, which produces a bright sonority, historically central to music from the countryside and rural cultural expression.

Sonic geographies are central to the residency. From the outset, the concert resisted reducing Puerto Rican Blackness to coastal imaginaries

This setting repositioned Afro–Puerto Rican cultural life within the island’s interior, unsettling dominant geographies of negritud. The billboard, intruding on the natural landscape, symbolized land exploitation and capitalist encroachment. By blending the cuatro’s timbre with Black aesthetics, Bad Bunny unsettled the notion of música típica as the island’s most “authentic,” non-Black expression, transforming the stage itself into a site of contestation.

After the rave-like eruption of “El Apagón,” the mood softened. Under a tree with only a guitarist, Bad Bunny sang “VETE” and “TURiSTA.” The sudden quiet peeled away spectacle, evoking intimacy and loss. Reggaetón, often dismissed as pleasure-only, revealed its veins of melancholy and vulnerability.

Bad Bunny spotlighted working- and middle-class urban experiences often erased from glossy island imaginaries. The marquesina became a vital socio-cultural space: a vessel of youth, memory, and diasporic mourning.

The focus then shifted to the now-iconic casita, a secondary stage evoking the party de marquesina (Puerto Rican open air garage parties). Here, perreo nostalgia surged with “Safaera” and “EoO.” By conjuring this rite of passage from adolescence to adulthood, Bad Bunny spotlighted working- and middle-class urban experiences often erased from glossy island imaginaries. The marquesina became a vital socio-cultural space: a vessel of youth, memory, and diasporic mourning. For those abroad, it was a sudden return home. For those on the island, a fragile yet enduring ritual of social life.

Every night, new internationally renowned artists attend the party at the casita. Some of the stars include Ivy Queen, Penélope Cruz, Zuleyka Rivera, Benicio del Toro, and Jon Hamm. On this particular evening, the night’s special guest was Arcángel, who stormed in with “Me Acostumbré,” pulling the show into Latin trap and underscoring Bad Bunny’s versatility and origins. Then Los Pleneros de la Cresta burst into the casita, flooding it with plena, often called the island’s sung newspaper, a popular tradition of working-class expression where social critique, gossip, resistance, and joy circulate through rhythm and verse.

Back on the main stage, “LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAii” (What Came to Pass in Hawai’i) mourned an island scarred by colonialism, militarization, and exploitation. The resonance with Puerto Rico was undeniable: two archipelagos commodified, their people sidelined, their sovereignty stolen. Hawai’i’s forced statehood in 1959 resonates directly with Puerto Rico’s unresolved status; two nations bound by shared wounds and the fight for self-determination.

Then came salsa. El Búho Loco, one of the island’s beloved salsa radio voices, narrated the genre’s history before ushering in Los Sobrinos, a young orchestra carrying salsa forward. Their set – “ CALLAÍTA,” “BAILE INoLVIDABLE,” “DtMF (DEBÍ tIRAR MÁS FOTOS),” “LA MuDANZA”– affirmed memory and belonging. During “LA MuDANZA,” the demand that only Puerto Ricans shout “¡Yo soy de P FKN R! (I am from P FKN R)” crystallized the central tension: how to go global without losing the local specificity of Puerto Rican sensibilities.

Over three hours, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio delivered a meticulously orchestrated performance that swung between celebratory, defiant, and intimate, always centering the communal. Every beat and image built a sonic and spatial narrative that, while rooted in Puerto Rican experience, resonated worldwide. His curatorial choices underscored his iconhood, his refusal to abandon Puerto Rico, and his call to shield the island from exploitative foreign interests.

Through every genre pivot and spatial cue, Bad Bunny staged a refusal, a reminder that Puerto Rico is not for sale. Even within the contradictions of capitalist spectacle, the desire for sovereignty pulsed through. For three hours, I too believed I would never leave Puerto Rico. I danced, I remembered, I wept. But when the lights came up, I carried with me the aftertaste of diaspora: the endless motion, the grief of always departing, and the fragile joy of staying — if only in song.

Bad Bunny’s residency runs from July 11 through September 14, 2025, spanning 30 concerts. He will then embark on his “Debí Tirar Más Fotos” World Tour, which is set to kick off on November 21, 2025, in Santo Domingo and run through July 22, 2026, spanning Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America.

Wilfredo José Burgos Matos, Ph.D., is a writer, academic, and performance artist. His book project tentatively titled “Amargue: The Communal Ecologies of a Dominican Feeling,” examines the affective, cultural, and sociohistorical dimensions of Dominican and Dominican-American communal life through the lens of sonic affect and emotional expression. He has published and presented his work in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Spain, Cuba, Haiti, and the United States. He specializes in Caribbean sounds, music, and affective geographies. Learn more about him at wilfredojose.com.

Squaring the Circle: The Violence of Environmental Form in the Colonial Caribbean

Squaring the Circle: The Violence of Environmental Form in the Colonial Caribbean

This blog post accompanies the article “Squaring the Circle: The Violence of Environmental Form in the Colonial Caribbean” in Small Axe 77 (July 2025).

by C.C. McKee

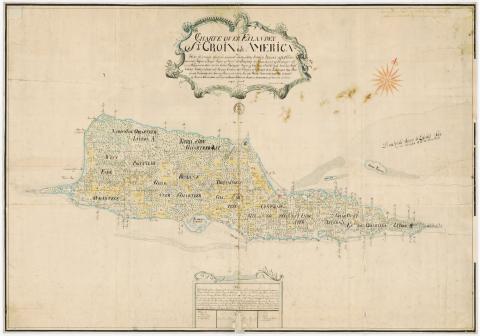

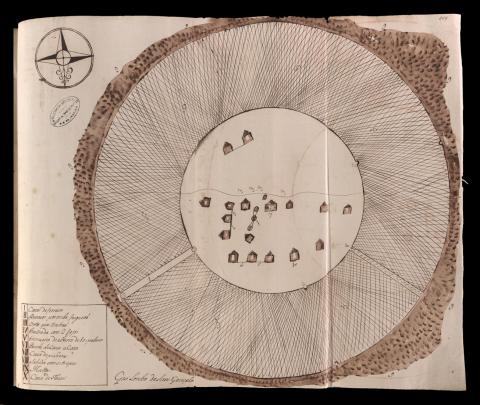

This article begins from the mathematical problem of squaring the circle— using only a compass and straightedge to construct a square with the same area as a given circle—as a method to build upon previous art historical and visual cultural scholarship on the history of slavery and the excessive violence it exercised upon Afro-descended peoples in the Caribbean.

Beyond a reinscription of the racialized body as the ur-site of colonial violence, this essay takes up current debates surrounding formalist method in a range of intersecting fields—film studies, Black theory, visual culture studies, and ecocritical theory—to return to geometric form as a means of locating the pervasiveness of ontological evisceration across scale.

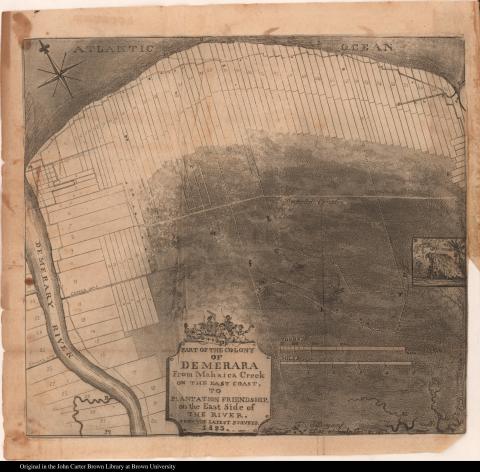

And yet, alongside the hegemonic power structures belied by these circular and rectangular shapes, this essay also locates moments of Black persistence in the Caribbean landscape. I trace this tension between circularity and rectilinearity across the Danish and French Caribbean colonies in the mid- to late-eighteenth century.

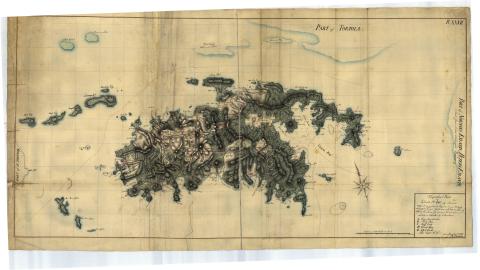

The maps and prints included here are referenced in the printed essay. Because this essay discusses at length images of anti-black violence in the form of execution, I have chosen to reference those images as blurred with a link for readers to see the original.

Dialogues in Caribbean Modernism: A Small Axe Symposium

Dialogues in Caribbean Modernism: A Small Axe Symposium

Artists, scholars, writers, and art practitioners gathered at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, on 24 and 25 October for the second iteration of the Small Axe Caribbean Modernisms project. The symposium challenged the Western formation of modernism as an artistic style and its effect on a set of artistic and intellectual practices in the Caribbean and its diasporas to make a case for “Caribbean modernism.”

By Dantaé Elliot

The first Caribbean Modernisms Symposium was held in Amsterdam, NL from 9 to 11 November 2023, and explored the questions, what and when was Caribbean modernism? The recordings and papers generated during that symposium are now available on our website.

The most recent symposium was organized around intergenerational, interisland, and interdisciplinary conversations to explore the forces that shape contemporary Caribbean literature, art, and discourses about injustice and struggles against it. Presenters from Puerto Rico, Haiti, Jamaica, Suriname, Curaçao, and the diaspora dialogued with each other about the emergence of new aesthetic styles and cultural-political languages developed by Caribbean writers and artist that respond to modernism similarly but with crucial differences that consider memory, time, space, and locality.

Évelyne Trouillot and Régine Jean-Charles

Roque Raquel Salas Rivera and Évelyne Trouillot at Casa de Cultura Ruth, Poetry evening

Mayra Santos-Febres at Casa de Cultura Ruth, Poetry evening

The conversations spoke to the malleability of the diasporic Caribbean and the region, which blends linguistic and visual elements (Caribbean Creole, French, Spanish, English, Haitian Kreyòl, and Dutch) as points of intersections for discussing Caribbean modernism as a process rather than a specific time and place.

The symposium concluded with a roundtable of invited artists and curators at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo on 26 October. The conversation addressed some challenges art institutions face in the Caribbean and the complexities of producing intra-regional exhibitions, precisely highlighting Puerto Rico as a colony/territory. In this regional dialogue, artists and art practitioners in Puerto Rico imagined ways to materialize more collaborative projects through different Caribbean art institutions.

Dialogues in Caribbean Modernisms made space for the participants to wrestle with the inconsistencies and limitations of modernity by considering the transnational and multilingual position of the Caribbean and its refusal of a category and creating alternative forms of knowledge, be it ancestral, Indigenous, environmental, or community-based.

You can learn more about Dialogues in Caribbean Modernisms by visiting our website.

Meet the Small Axe 2024 - 2025 Editorial Assistants

We are happy to welcome Laura, Caprie, and Luis who are joining our team as editorial assistants. And welcome back Dantaé, a returning assistant. We also thank our outgoing editorial assistants for all of their intellectual and organizational contributions to the Small Axe Project.

Meet our incoming Editorial Assistants:

Laura Berríos is a PhD student in the Department of Latin American and Iberian Cultures at Columbia University. Her research examines representations of violence and narcoculture in contemporary literature and popular music from the Spanish-speaking Caribbean. She holds a B.A. in Hispanic Studies from the University of Puerto Rico. As an undergraduate, Laura was a Mellon Mays Fellow and worked as a youth tutor with the community-based initiave Huerto, Vivero y Bosque Urbano de Capetillo in Río Piedras.

Luis Frías is a New York-based scholar and writer pursuing a PhD in Latin American, Iberian, and Latino Cultures at the CUNY Graduate Center. Luis’s interests revolve around Mexican literature and cinema, archives, feminism, masculinities, violence, and neoliberalism. He splits his time between parenting his 4-year-old son, Leo, writing his dissertation, teaching Spanish and Portuguese languages, and wrapping up a book of tales. His current obsession is improving his times to run the 2025 NYC Marathon.

Caprie Hughley is a student at Queens College earning my bachelor’s degree in English. Reading and writing are two things she enjoys doing. Which is why she loves creating content on authors, books, and my opinions of the books I read. "Having a platform to help up in coming writers is needed and is why I create the content," she says. "Becoming a part of the Small Axe team is an honor and I am excited about what this semester has in store for me."

Dantaé Elliott is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at New York University. She has a particular interest in contemporary Caribbean Art and its relation to migration within the Caribbean diaspora and region, while examining the phenomenon “barrel children syndrome.” She is a featured artist in Volume 4 of Forgotten Lands, titled Currents of Africa, released in June 2022. Dantaé is a returning editorial assistant.

Thanks to our outgoing Editorial Assistants:

Tyler Grand Pre is a PhD candidate in the Department of English and Comparative Literature and ICLS affiliate at Columbia University. His research revolves around poetic responses to the infrastructure of race—that is, the networks of technologies, materials, and, as he argues, representational practices that structure the social, economic and spatial hierarchies of race. Tyler examines the way different writers and artists respond to the built and mapped environment to reimagine community both within and without the borders of language, race, and geography.

Mayaki Kimba is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at Columbia University, specializing in political theory. His research interests concern the legacy of empire in shaping ideas around race and migration in twentieth-century Western Europe. Other and related interests include Black political thought, anticolonial political thought, (social) citizenship and the welfare state. He was born and raised in the Netherlands, and graduated with a B.A. in political science from Reed College in May 2020. His essay on T. H. Marshall, late imperial ideology and racialized migrant exclusion was selected for a 2020 award by the Undergraduate Essay Prize Committee of the North American Conference on British Studies.

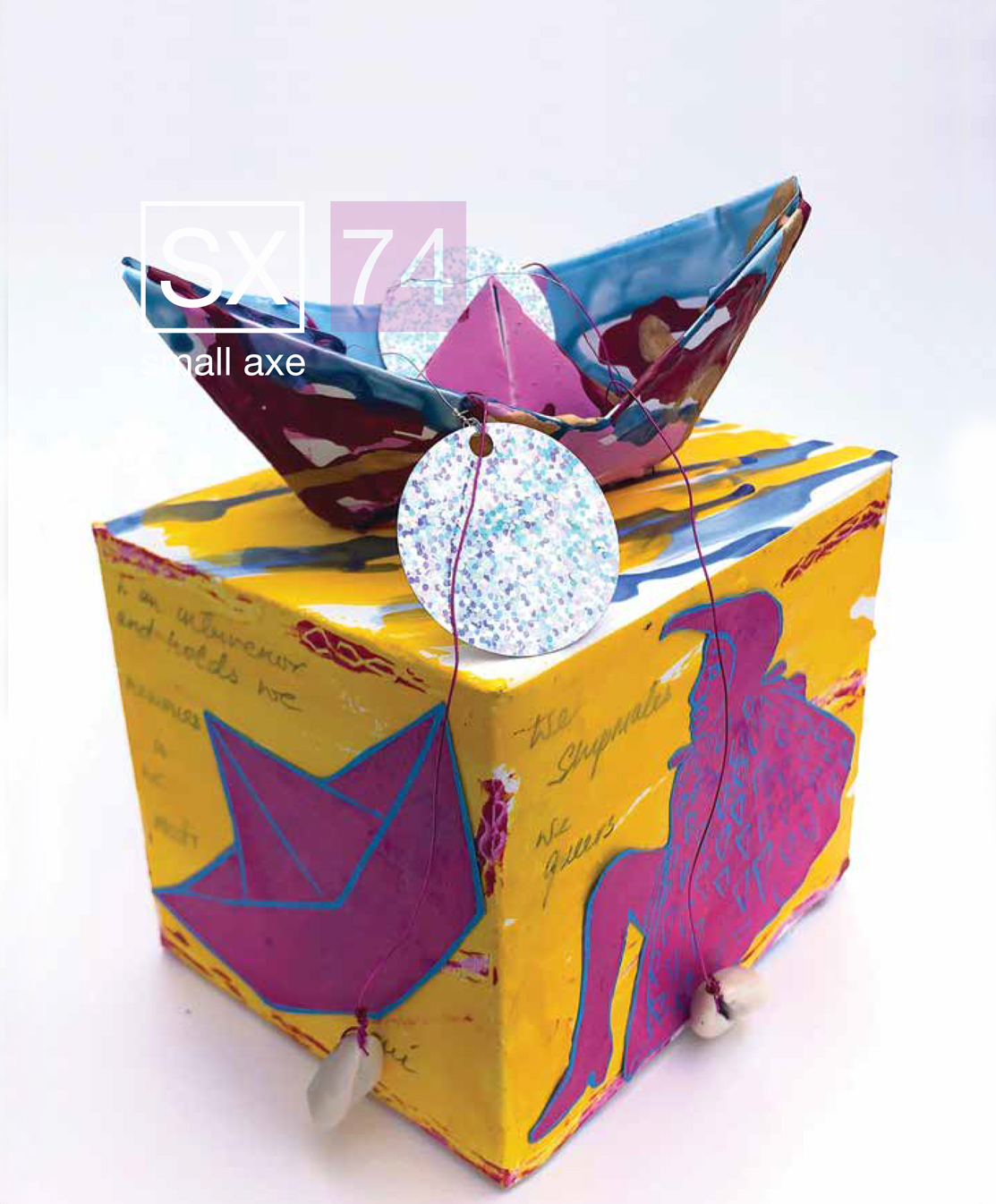

SX 74 is here!

SX 74 is here!

Small Axe 74 includes essays by Fatoumata Seck, Mary Grace Albanese, and Mónica B. Ocasio Vega. The special section on "The Cultural Poetics of Carolyn Cooper" features work by Nadi Edwards, Louis Chude-Sokei, Nadia Ellis, Ananya Jahanara Kabir, Njelle Hamilton, and Carolyn Cooper. In this issue we publish the third iteration of our Keywords project with an exploration into the critical terms used to theorize Caribbean sexualities with essays by Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes, Wigbertson Julian Isenia, Krystal Ghysyawan, and Jacqueline Couti. The cover and visualities essay "Buss head Hard head," showcases the art of Natalie Wood. Rocío Zambrana's book Colonial Debts: The Case of Puerto Rico is discussed by Judith Rodriguez, Ernesto Blanes-Martinez, and Agustin Lao-Montes.