Geographies of Sabor: Loíza, Countryside, and Food Practices in Puerto Rico

Mónica B. Ocasio Vega

Geographies of Sabor: Loíza, Countryside, and Food Practices in Puerto Rico

Mónica B. Ocasio Vega

On a sunny Mother’s Day my family and I drive from the town center of my hometown Cabo Rojo to the Llanos Tuna neighborhood: del pueblo al campo. We drive to my great grandmother’s house, abuela Blanca, in what feels like a certain ritual or pilgrimage to the home of our living ancestors, the matriarch of the family whose knowledge and experiences sustain the present versions of ourselves. At abuela Blanca’s home every single stove burner and counter space is occupied by a part of what will be the family lunch. The house is filled with the sound of frying sorullitos de maíz and almojábanas and with the invasive aroma of the arroz con pollo: when the combination of steam, fat, and sofrito announce its doneness.

Abuela Blanca was from el campo or the countryside, a space often represented as mythical in Puerto Rican culture. It is in this space as well as other rural spaces outside of the urban scenery where “real” Puerto Rican food is made by the mythical jíbaros. My siblings and I always identified abuela Blanca’s cooking as the true comida sabrosa in our family.

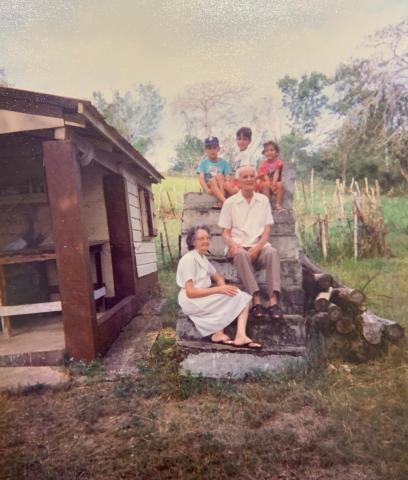

My great grandmother Blanca Rosa Zapata Pérez, my great grandfather Luis Ángel Ramírez Asencio, my siblings Luis Manuel Ocasio Vega and César Enrique Ocasio Vega, and myself on my great grandparents' home in Llanos Tuna, Cabo Rojo.

We saw this as a relation to something intangible, always in fugue, yet present in the senses when we ate her food. Many Puerto Ricans hold similar relations to women’s cooking in their families and often rely on social media as a medium to remember them and replicate their creations. While akin to memories of their loved ones, oftentimes these culinary nostalgic references in Puerto Rico are built upon preconceived notions of gender, race, and space. This results in spaces like the coastal town of Loíza or the countryside, and culinary practices such as cooking empanadas on the burénor pasteles, being overrepresented as the places where sabor o la comida sabrosaoriginates. While these types of over representations attempt at anchoring cooks to a specific time-space, the central trait of that which we consider true comida sabrosa is its escape, a refusal to be situated. In my Small Axe 74 essay “From Loíza to Yauco’s Mountainous Area: Two Instances of Fugitive Food Practices in Puerto Rico,” I write about two Puerto Rican cooks who develop a relation to food that stems from fugitive practices of space which originate in slave-based plantation and subsistence economies. I follow cooks María Dolores “Lula” de Jesús from Loíza and Viña “la Gran Pastelera” Hernández from Yauco as they re-signify affective networks that make up nostalgic imageries often grounded in prescriptions of race and gender. Given that composition of this imagery is multisensorial, it is not entirely translatable in written form. Because of this untranslatability, I want to use the space of the digital to revisit some reflections I begin in the essay which center the logic of the senses.

The opening shot of the episode titled “El Burén de Lula” in the YouTube series Eat, Drink, Share Puerto Ricoshows a house-like structure made up of different materials: concrete, pieces of diverse woods, and zinc. Guided by the image of a sign and a crowing rooster, we learn this place is el Burén de Lula. The combination of these two sensorial images transports viewers to the space and time of the coast, almost tasting the salt in the air and smelling the burning firewood: the preferred heat source for cooking in food establishments in Loíza. The following shot moves inside of the kitchen, where the camera captures de Jesús from the back. Two images follow: a side profile shot of de Jesús’s face and the olla (cooking pot), which is visibly used, or curada (seasoned or cured), as it is often said in Puerto Rico. The voice of de Jesús immediately guides these images. Then—in a change of scenes—de Jesús talks to the viewer directly in the form of an interview: “I would say I’m a blessed woman. It hasn’t been easy. I have diabetes, high blood pressure, and the glaucoma I told you about. I never worked because my husband never allowed me to. Never!” The story of how de Jesús came to open and own her restaurant serves as a contextualization for the dishes the audience is about to witness: arroz con jueyes (rice with land blue crabs), dulce de coco (coconut fudge), cazuela de calabaza y batata (pumpkin and sweet potato casserole), and a mix of patties, arepas, and cassava bread.

"Understanding these preconceived notions of race and gender, Lula challenges which places Blackness is allowed to occupy and what culinary practices Black people can engage in"

El Burén de Lula is a restaurant located in the Jobos sector in the northeastern town of Loíza, Puerto Rico and it is named after its owner, María Dolores “Lula” de Jesús. Because Loíza has been deemed as the designated space of Blackness in Puerto Rico, I find it important to note how sensorial cues such as burning firewood, the sound of frying oil, and the taste of crisp and oily alcapurrias often attempt at fixing cooks who prepare these foods to this space. Further, foodscapes are tied to the construction of spaces that are gendered and racialized. Understanding these preconceived notions of race and gender, Lula challenges which places Blackness is allowed to occupy and what culinary practices Black people can engage in. After all, the seven recipes in the twelve-minute and fifty-six- second video are prepared in the indigenous Taíno clay cooking surface, known as the burén. By bringing together the centrality of the burén and the generational knowledge Lula embodies, I find this episode posits de Jesús—her body, her voice, and her expertise of Afro-Taíno foodways—front and center of the story. In doing so, it allows the Afro–Puerto Rican woman to narrate her story.

Sensorial imagery also plays an important role in the representation of the Puerto Rican countryside, often referred to as el campo. Viña Hernández, popularly known as “la Gran Pastelera,” launched her Facebook page in 2016. There she shares recipes either by uploading videos or by live streaming from her home in Yauco’s mountainous area in Puerto Rico, a reference she makes as a signature sign-off in her videos. This form of identification serves as an assertion of the ways of living that are often perceived as frozen in time, disconnected from notions of progress. The recipe for pasteles includes a distinct rural Puerto Rican soundscape with the recurring crowing of the rooster. This soundscape, intertwined with Hernández’s instructions, contributes to viewer comments romanticizing the purity of the countryside in Puerto Rico: an idealized image of rural life that characterized literary and cultural productions of the latter half of the twentieth century. Nonetheless, Hernández’s culinary and spatial practices defy rural modernization and instead utilize the nostalgic crystallization of rural life to demonstrate visually and sensorially the vibrant existence of people in el campo. Further, her relationship with space can be understood as a form of marronage in the ways in which her practices of space are constantly evolving, escaping, and negotiating nostalgic imagery; challenging static representations of el campo and fading traditions.

Read Mónica Ocasio's full essay "From Loíza to Yauco’s Mountainous Area: Fugitive Food Practices in Puerto Rico" in Small Axe 74, July 2024.

Author Bio

Mónica B. Ocasio Vega is a Puerto Rican scholar who works at the intersection of food, race, and gender in the Hispanic Caribbean and its diasporas. She is currently an assistant professor of Spanish in the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas.