sx blog

Our digital space for brief commentary and reflection on cultural, political, and intellectual events. We feature supplementary materials that enhance the content of our multiple platforms.

Nicole Awai: Vistas on view at Lesley Heller Workspace

Nicole Awai: Vistas on view at Lesley Heller Workspace

Nicole Awai: Vistas (http://www.lesleyheller.com/exhibitions/20170517-nicole-awai-vistas)

May 17 – June 30, 2017

vista

• a mental view of a succession of remembered or anticipated events: vistas of freedom seemed to open ahead of him

Lesley Heller Workspace is pleased to present Nicole Awai: Vistas, the artist’s first exhibition with the gallery. Nicole Awai is known for her multi-media works that make use of non-traditional mediums such as melted vinyl, nail polish, nylon mesh, found doll parts, and synthetic paper. Her work references and is influenced by the Caribbean landscape, in particular the La Brea Pitch Lake in Trinidad, her country of birth.

Vistas is comprised of a series Awai has been creating since the mid 2000s where she has been in part, exploring characteristics of oozing in her work. The specific works in this show—produced between 2013 to 2017—were made following a 2012 Art Matters Grant the artist received to travel back to Trinidad to visit the La Brea Pitch Lake—the largest natural deposit of asphalt in the world. Awai was searching for connections or influences to explain the use of black oozing in her work. The tar-like substance becomes an archaeological framework in her artworks to preserve and represent visual and cultural materials; a fluid yet stable visual and symbolic ground from which to explore cultural dialogs.

Vistas are the momentary glimpses of an experience. The ooze serves as a junction or space for her to engage and infuse a diverse set of meanings. Awai states that she has “come to understand that this black oozing materiality is in actuality a site of confluence - of our histories, our physical existence and the elasticity of time, space and place in the Americas.”

Nicole Awai's work is featured in the current issue of Small Axe (52), special issue, Art as Caribbean Feminist Practice

Oozing between Dimensions: Multiple Perspectives on the Real in the Works of Nicole Awai, by Michelle Stephens

Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism

http://smallaxe.dukejournals.org/content/21/1_52/43.abstract

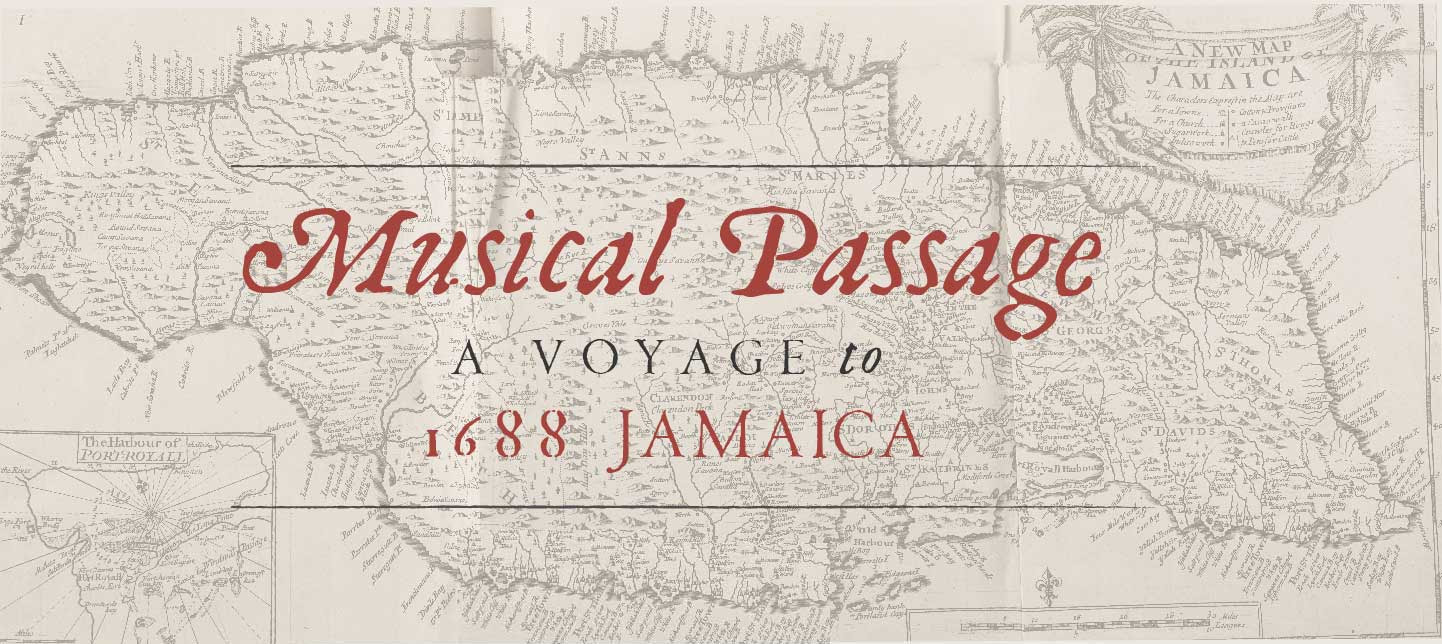

Digital Annotation of Musical Passage: A Voyage to 1688 Jamaica

Digital Annotation of Musical Passage: A Voyage to 1688 Jamaica

sx archipelagos will host a series of week-long experimental events to reconnect our audiences with the content of our inaugural issue. In an effort to truly take advantage of - and not merely pay lip service to - the affordances of the digital, we are interested in maximizing the dynamic presence of the journal's content in the world - beyond the periodicity of publication. As such, we have initiated a commons space of sorts - punctual opportunities for our community of readers to enter into dialogue with our contributors, leaving comments on and posing questions about their work via the open annotation tool hypothes.is. Contributors will monitor their pages throughout the week-long commons event, responding to and engaging with their audience.

Please join us in this experiment by checking out Laurent Dubois, David Garner, and Mary Caton Lingold's Musical Passage - June 19-23. To leave a comment or ask a question, simply set up an account with hypothes.is. Once you've done that, engaging with the site is as easy as selecting the passage you want to address, and clicking on the comment button. For more detailed instructions, the creators of the tool have provided excellent documentation. You might also have a look at this video. Note that the technology works best on the Chrome browser.

She'll Chew You Up: Tiana Reid on Safiya Sinclair and Tiphanie Yanique

Tiana Reid, Small Axe's editorial assistant, has recently published a piece for Cordite Poetry Review on Safiya Sinclair's debut book of poems, Cannibal, and Tiphanie Yanique's 2015 Wife. "If the novel form is a question mark," she asks," then, and while reading...Cannibal... I thought the poetic form might as well be an em dash. Versatile, incidental, fragmented, paratactic, broken down and broken into."

To read Tiana's full review, please visit Cordite's website.

Tiana Reid is a writer whose work has been published in ARC Magazine, Bitch, Briarpatch, The Feminist Wire, Full Stop, Lemon Hound, Maisonneuve, Mask Magazine, The New Inquiry, Rabble.ca, The Rumpus, The Toast, VICE and more. She is a PhD student in English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and editorial assistant at Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism.