sx blog

Our digital space for brief commentary and reflection on cultural, political, and intellectual events. We feature supplementary materials that enhance the content of our multiple platforms.

The 12th Annual Festival of Language 2020: March 4, 2020 at Cherrity Bar in San Antonio, TX (4:30-9:30 pm)

The 12th Annual Festival of Language 2020 brings together 33 poets and writers from more than a dozen states and a couple of countries to perform flash readings from their works in a celebration of innovation, creativity, inclusion, and words. Free. Pre-reading gathering starts @4:30pm, first readers at 5pm. Hosted by Ted Pelton.

The lineup includes poet Rosamond S. King, associate professor of English at Brooklyn College and author of Island Bodies: Transgressive Sexualities in the Caribbean Imagination (University Press of Florida, 2014). King will read from 6-7 pm.

When: Wednesday, March 4th, 2020, 4:30-6:30 pm

Location: Cherrity Bar: 302 Montana St, San Antonio, TX 78203

Facebook Event Page: https://www.facebook.com/events/192112255226121

ANCESTRAL QUEENDOM: Reflections on the Prison Records of the Rebel Queens of the 1878 Fireburn in St. Croix, USVI

The Virgin Islands Studies Collective (La Vaughn Belle, Tami Navarro, Hadiya Sewer and Tiphanie Yanique) published a collaborative article in NTiK entitled "Ancestral Queendom: Reflections on the Prison Records of the Rebel Queens of the 1878 Fireburn in St. Croix, USVI (formerly the Danish West Indies)." Each member responds to one of the prison records of the four women taken to Denmark for their participation in the largest labor revolt in Danish colonial history. Their reflections combine elements of speculation, fiction, black feminitist theory and critique as modes of responding to the gaps and silences in the archive, as well as finding new questions to be asked.

Check out their promo video: https://youtu.be/a748f-8NzlE

IN ALL MY DREAMS: A Visual Installation

Date: Friday, February 21

Venue: Louise McCagg Gallery at Barnard College

Time: 7-9pm

Join us for the opening of IN ALL MY DREAMS, a collective, multivalent project situated at the intersections of literature, history, and visual art in the Caribbean.

Contemporary artists Nathalie Jolivert, Tessa Mars, and Mafalda Mondestin propose an extraordinary, multi-dimensional visual dialogue with famed Haitian author René Depestre’s novel Hadriana In All My Dreams. In crafting vibrant new ways of bringing Depestre’s work into the world, they present an arguably less common vision of what Haiti, its writers, and its artists offer on the global stage.

Artists Talk, moderated by Dominique Jean-Louis, will begin promptly at 7:30pm. Light refreshments will be served.

For further details, be sure to visit the exhibition website.

RVSP here.

#1619Project and the Anti-Racist Road Not Taken, an essay by Harvey Neptune

With #1619Project The New York Times has embarked upon a momentous reinterpretation of US history, one that centers African Americans in a national narrative driven by brutal economic exploitation and progressive democratic resistance. The brainchild of acclaimed journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, this multimedia, multi-platform production represents a massive corporate investment in public history -- a scale of investment at The Times perhaps last seen in the 1940s when it helped to sponsor the publication of the Jefferson papers. Not surprisingly, the underlying interpretive frame for #1619Project, a compelling historiographical mashup of Afro-pessimism and Afro-exceptionalism, has won plenty professional endorsement, especially within the academy’s “progressive” wing. Equally unsurprising is the fact that Hannah-Jones’ powerful and disruptive intervention has generated push-back. The project’s simultaneous incrimination of traditional patriotic heroes and recuperation of black people’s special role in redeeming the nation has rankled a few members of the profession’s “validating elite,” to borrow a term from Lloyd Best.

As a practicing student of history, I of course deeply appreciate #1619Project and welcome it as a strong stimulant for a profession that struggles to stay woke. Yet, I too have a deep reservation about a fundamental aspect of Hannah-Jones’ framing. My issue, it should be stated from the outset, is contrary to the criticism voiced by some of my senior colleagues.* Whereas they appear anxious that #1619Project represents the “ideology” of antiracism gone too cynically far (a case of white lives like Lincoln’s mattering too little?), I am concerned that the reinterpretation marks a conservative retreat from the much-needed materialist road of anti-racist historiography.

How so? The problem lies in the project’s implicit naturalization of race, a process essential to all racist thought. Presumed in Hannah-Jones’ narrative is an understanding that the twenty Africans who arrived in Virginia in August 1619 were racialized from day one and on that basis deemed fit for slavery. “Those men and women who came ashore on the August day were the beginning of American slavery,” she writes. Charmingly simple and seemingly factual, this statement should actually give pause. It is a presumption, in fact, that rushes over a long-running and consequential debate about the status of those twenty Africans, about whether they were slaves and, indeed, whether they were viewed through the lens of “race.” Ignoring this quarrel over the significance of “August, 1619,” Hannah-Jones ends up disregarding a radical tradition of anti-racist history-writing that disagrees with her interpretation of that date as an inaugural moment for a nation historically founded on racism and black enslavement. The result is a silencing of authors (often non-white and wielding an historical materialist approach) concerned to demonstrate that race was not obvious and natural from inception but was produced under specific conditions.

As history would have it, on the very day that #1619Project dropped, Nell Painter voiced this longstanding objection to Jones’ founding premise about 1619. In an op-ed that targeted President’s Trump’s use of “enslaved” to describe the 20 Virginia arrivants of 1619, Painter insisted that these Africans were not slaves and, moreover, were not yet subject to the ideology of race. It was not “until the eighteenth century that we find the more familiar, hardened boundaries of racialized American identity,” she wrote. Painter then went on to blame the “ideology of race” for encouraging people like Trump to tell a history in which “the Jamestown Africans of 1619 are always already enslaved” and in which “Africans and their descendants are the same as slaves.” In Painter’s view, it was conventionally racist to presume that the 20 Africans who came ashore were viewed as racial inferiors fit for enslavement.

The failure to engage this argument against “1619” as an inaugural date is remarkable if not curious in an historical project that drew on the best of professional consultants. After all, the academic debate over the beginnings of slavery and racism in North America has been so enduring and intense that -- like many of these Ivory Tower affairs -- it acquired a brand: “the origins debate.” This scholarly quarrel took off in the middle of the 20th century and featured, on one side, memorable authors like Eric Williams and the marital team of Mary and Oscar Handlin. To these historians, the enslavement of Africans was neither immediate nor originally rationalized through race-thinking. As Williams famously phrased it in Capitalism and Slavery (1944), “slavery was not borne of racism, rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.” A few years later, the Handlins made a remarkably similar argument in an article that -- unlike Williams’ book -- focused more on slavery in North America than in the Caribbean. Slavery and racism, they argued, were not stamped on Africans from inception; rather, both emerged toward end of the 17th century, conditioned by the demands of developing capitalist plantations.

The Handlins’ argument against the inaugural import of 1619 actually became conventional wisdom for a quick academic minute. By the fifties, though, it began to come under attack, first by Carl Degler, and then, more influentially, by Winthrop Jordan. Jordan’s award-winning White Over Black, though sometimes uncertain and even confusing in its argument against the Handlins, nevertheless restored “August, 1619” as a significant beginning. By that date, according to Jordan, it would have been so natural to view the twenty African arrivals as members of an inferior race that their enslavement amounted to an “unthinking decision.”

While this is not the place to referee the academic “origins debate,” it is critical to comprehend that the stakes were anything but academic. For Williams, the Handlins and their followers, the point of contending that the idea of black inferiority did not prevail from the start in 1619 was to advance the goal of denaturalizing race. Appreciating that racism relies on the naturalization of race, they contributed to a wider intellectual move to expose race as an idea in history, indeed, as one of “man’s most dangerous ideas,” to cite Ashley Montagu’s anti-racist classic. In their view, blackness and whiteness were inventions (not only Nell Painter but scholars like Silvia Federici, Toni Morrison and Barbara Fields would develop and refine this line of argument.) At stake for historians like the Handlins was an understanding that race, because it was made in the past, could be unmade in the future. This was no easy optimism, as some have suggested. It was the urgent antiracist thinking of an age that had witnessed the atrocities of World War II.

On the other side of the “origins debate,” Jordan was not what we would think of as a stereotypical ‘racist;’ yet, it is important to recognize that his analysis effectively naturalized race, despite explicitly opposing white supremacy. In fact, it should have come as no surprise to close readers that Jordan ended White Over Black with a “Note on the Concept of Race” that affirmed race as biology. To the extent that Jordan’s monumental work has been persuasive in the debate about the significance of “1619,” it represented a setback for anti-racist history-writing.

Indeed, there is a rich irony in the fact that #1619Project effectively follows Jordan’s naturalizing lead rather than the historical road paved by Williams and the Handlins. According to Hannah-Jones, a crucial source of inspiration for the project came from a teenage encounter with a book by Lerone Bennett, the recently passed writer, scholar and magazine editor. Reading Bennett’s Before The Mayflower: A History of Black America proved to be a “revelation” for her. Started as a series of articles in Ebony and first published in 1962, the book produced one of those “aha” moments that led Hannah-Jones to conceive of #1619. Given this story, it is indeed a revelation to pick up this book and to discover that Bennett not only had a stake in the “origins debate” ignored by Hannah-Jones but also that he opposed Jordan and took the anti-racist side of Williams and the Handlins.

In Before The Mayflower, Bennett writes: “But the first black immigrants were not slaves and this is of capital importance in the history of the Negro.” And a few lines further: “In Virginia then, as in other colonies, the first Negroes fell into a socio-economic groove that carried no implications of racial inferiority. That came later. But in the interim, a period of forty years or more, the first black settlers accumulated land, voted, testified in court and mingled with whites on the basis of equality.” Bennett’s rejection of the inaugural significance of 1619 was even more emphatic in an Ebony essay published a few years later. Titled “The Road Not Taken,” this 1970 article stated plainly that “[i]n the beginning there was no race problem in America. The race problem in America was the deliberate invention of men who systematically separated blacks and whites and reds to make money.” The rest of the essay analyzed the rise of enslavement and racism in North America, placing particular emphasis on context and the interested “choices” that conditioned their emergence.

And here, in this stress on material interest, context and “choice,” lies the ultimate reason why #1619Project should engage seriously the arguments of authors like the Handlins, Bennett and Painter. Their emphasis on conditions, power and agency provides the vital and critical reminder that the making of our racist society has not been inevitable, that the roots of white supremacy lies neither in destiny nor DNA. Rather, the nation’s historically racist order reflects the results of decisions, often well calculated, made by people with control over powerful institutions. This is a crucial lesson for the young readership being cultivated by The Times. It is important that they not be misled into thinking that it is somehow natural to perceive a mortal threat in superficial bodily factors like black skin and broad noses. They must be exposed to histories that not only debunk white supremacy but also illuminate our complicity in reproducing the violent governing concept of race as we make it seem like a part of nature or -- no better -- an essentialized form of “culture.”

If the modern past of people of African descent has been thus far filled with so much death and despair that it necessitated a kind of historical scholarship I once dubbed “wake work,” the very survival of this community in the future demands something else: studies that expose the killing emptiness of the race idea, a genuine anti-racist intellectual labor that we might embrace as “life work.”**

Nuff thanks, as usual, to Donette Francis, Charisse Burden-Stelly and “PanchoD” for careful and caring engagement. And special thanks to my graduate seminar student Sarah Whites-Koditschek for her insightful work on #1619Project.

* See “Letter to The Editor: Historians Critique The 1619 Project, and We Respond,” The New York Times, December 20, 2019. Here is a good place to acknowledge that this essay is my own response to an invitation to respond to the #1619Project at the World Socialist Website.

** “Loving Through Loss: Reading Saidiya Hartman’s History of Black Hurt,” Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal, 6 1 (2008): article 6. Christina Sharpe would add nuance to the term later. See “Black Studies: In The Wake,” Black Scholar 44 2 (2014): 59-69.

"The Caribbean Digital VI" conference by sx archipelagos

"The Caribbean Digital VI" conference by sx archipelagos

Date: Friday, 6 December 2019

Venue: Barnard College Digital Humanities Center

Time: 1-8pm

Over the course of an afternoon of panel presentations and roundtable conversation, participants will engage critically with the digital as praxis, reflecting on the challenges and opportunities presented by the media technologies that ever more intensely reconfigure the social, historical, and geo-political contours of the Caribbean and its diasporas. Presenters will consider the affordances and limitations of the digital with respect to a wide range of disciplines and methodologies. As with every iteration of “The Caribbean Digital,” we look forward to picking up themes addressed in our previous conferences – many of which currently feature in the three issues of archipelagos journal, our peer-reviewed publishing platform dedicated to Caribbean digital scholarship and scholarship of the Caribbean digital.

British Black Cultural Archives digitized by Google

Black Cultural Archives (BCA), the only national archive for Black British history, brings its unique collection of images, artifacts and artworks together online for the first time (g.co/blackculturalarchives).

A two-year project in collaboration with Google Arts & Culture, the BCA have digitized over 4,000 items from their collection, forming a series of curated online exhibitions and stories which can be accessed globally to help inspire and educate. As Britain has a strong West Indian population, this new digital archive will contain many materials that tell the stories of Caribbean migrants and their descendants across the UK.

Available on the Google Arts & Culture website and app, the new digital collection utilises innovative technologies including ultra-high resolution Gigapixel photography using the Art Camera to help preserve these important histories for future generations, and to encourage enquiry and dialogue all over the world.

Text from the BCA website with minor edits

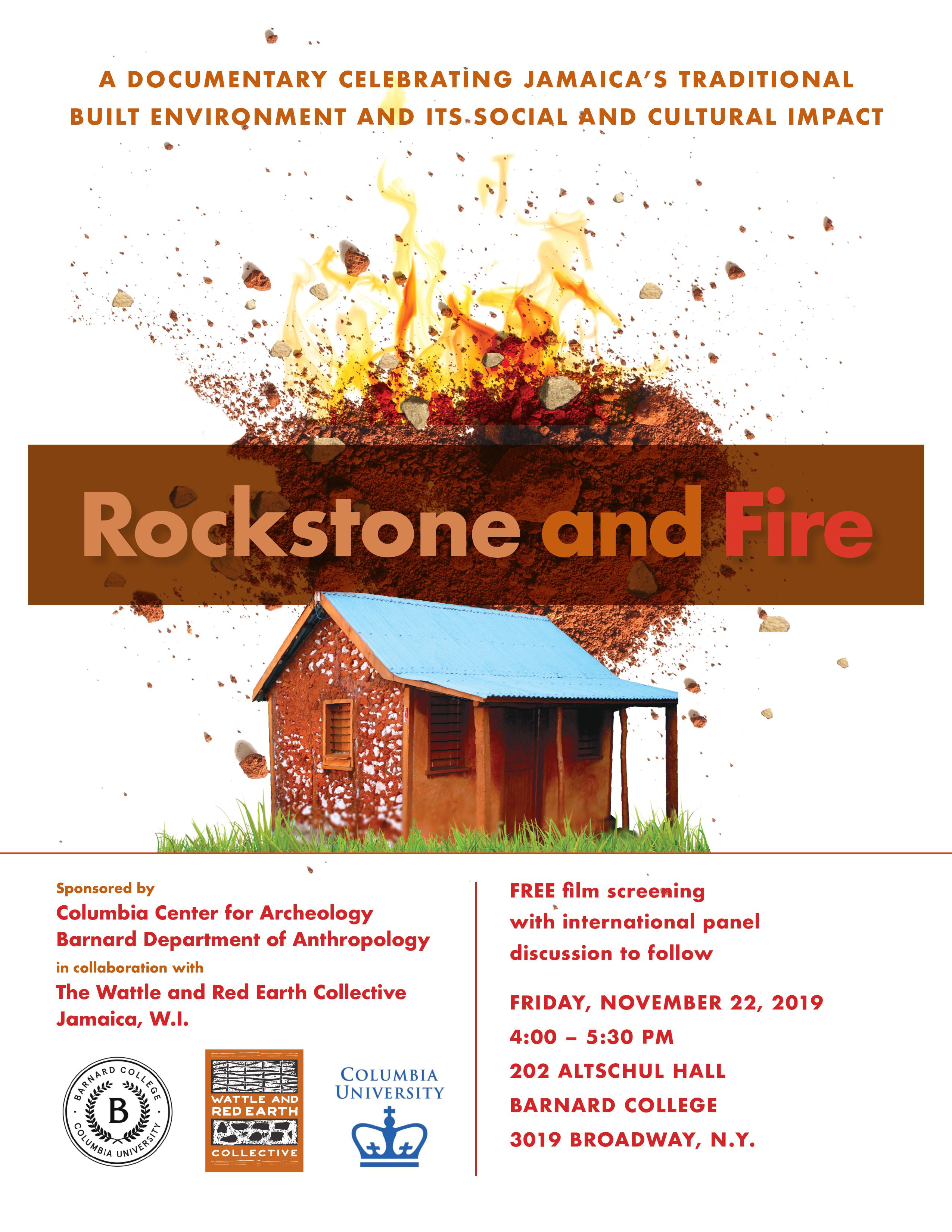

Jamaican documentary "Rockstone and Fire" screening at Barnard College

Date: Friday, 22 November 2019

Venue: Altschul Hall, Barnard Hall

Time: 4-5:30pm

In collaboration with the Wattle and Red Earth (WARE) Collective, the Columbia Center for Archeology and Barnard Department of Anthropology will be screening "Rockstone and Fire," a documentary exploring the rural architecture of post-emancipation Jamaica and the efforts of the WARE Collective to preserve Jamaican cultural heritage and traditional forms of environmentally-sustainable building techniques. Courtney Coke, the director, and other members of the WARE Collective will be present for a discussion following the screening. A trailer can be viewed at: https://filmfreeway.com/RockstoneandFire343.

SX editor David Scott interviewed by Public Anthropologist on upcoming Stuart Hall biography

International journal Public Anthropologist recently interviewed David Scott, Small Axe editor, on his relationship with Stuart Hall in light of his upcoming biography of the pioneering cultural theorist. Read below for an excerpt of the interview.

Sindre: First of all, David, I am going to cite one of my favorite passages from your own work on the late Stuart Hall (1932-2014). It is a moving tribute that you published already in 2005 in your journal Small Axe, entitled Stuart Hall’s Ethics. What strikes me is that this is in fact poetry. I have actually used it as an epigram in one of my own monographs. You wrote the following there, and this was at a time when Stuart Hall was still alive: “We live in dark times; they are not times that favor forbearance, they do not shelter generosity, they do not encourage receptivity. They are rather obdurate times, cynically, triumphalist and ruthlessly xenophobic times that seem to require new regime of silencing and assimilation. A new regime of prostration, submission and humiliation. Who, looking forward from a generation ago – in the middle of another imperial moment – could have imagined they would be living in a world that looks like this one. But Dark Times, as Hannah Arendt memorably said, need people who can give us illumination, and who calls them forth into the public realm.”

So, in order to talk about beginnings here David, who was your friend Stuart Hall and why does his work matter so much right here, right now?

David: Sindre, you begin with an impossible question. I thought you would begin with rather more elementary questions that would then take us gradually into the heart of the matter. But you begin with very, very large issues. So, let me try and find my way to your question. The passage that you read from was written roundabout in 2003-2004, and it was written for a really important event. Maybe we should begin there. It was the first time that a symposium had been organized at the University of the West Indies, Mona (the Jamaica campus of the University of the West Indies) in honor of Stuart Hall. It was a very telling and significant event, and as significant for Jamaican intellectuals as for Stuart. It was very significant for Stuart and for his relationship to Jamaica. My concern in my lecture (and it was the sort of keynote lecture delivered at the opening of the conference) was to try to present Stuart Hall in as broad a manner as possible—to try to characterize something about the texture of his orientation towards thinking, more so than to try to present the details of his particular conceptions of culture and politics. And so, part of what I wanted to evoke in the passage that you read was the signature way in which Stuart Hall entered conjunctures, as he might have called them, to try to unpack what he thought the dead-ends were, and to try to offer glimpses of alternative ways to think ourselves out of the present dark times. In many ways, that was his modus operandi. What was amazing about the character of the movement of his mind was a refusal to be imprisoned by the dark time of the present: the present was always for him a kind of challenge to unlock, to both re-describe the way in which the present appeared to us, and to re-describe it in such a way that we could see better where the present had come from—what kinds of pasts, and what kinds of pathways from the past, had led to this present. And to do so, moreover, in a way that would enable us to recognize the contingencies and the “constructedness” of the present so that we might think of the possibility of alternative futures. And that capacity, that uncanny capacity to re-describe the present as a way of thinking futurity, was to my mind unique.

Read the full interview here on Public Anthrologist's blog

The above interview excerpt was recorded at the House of Literature in Oslo on October 15, 2019. The interview has been transcribed by Gard Ringen Høibjerg (INN University College), and edited and amended for clarity by Sindre Bangstad, David Scott and Antonio De Lauri.

"I AM Queen Mary" Statue Welcome Ceremony at Barnard College

Date: Tuesday, Oct 15 2019

Venue: Barnard Hall

Time: 10:30am, 6pm and 6:30pm

Barnard Hall will welcome a scale replica of "I Am Queen Mary," a sculpture created by artists Jeannette Ehlers and sx60 cover artist La Vaughn Belle, on Tuesday October 15, 2019. The scale replica was commissioned by the Ford Foundation and will remain at Barnard for the next few years on an extended loan, facilitated by Ford Foundation Gallery Director Lisa Kim (Barnard class of 1996). The original monumental sculpture is on display in Copenhagen, Denmark. Read more about the original work here.

Attend the welcome ceremony on Tuesday at the following moments, all times approximate:

10:30am - Silent Welcome of the sculpture in the lobby of Barnard Hall

6pm - Welcome Ceremony, featuring La Vaughn Belle (Barnard Center for Research on Women Artist-in-Residence and co-creator of "I Am Queen Mary") and Ariana Gonzalez Stokas (Barnard Vice-President of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion)

6:30pm - Post-Welcome Ceremony Celebration - a party/celebration at BCRW on the 6th floor of the Milstein Center

During the Barnard spring semester, there will be a more substantive panel discussion of the issues raised by the sculpture about the politics of public art, representations of Black women in public art, the role of this sculpture on the Barnard campus, and more. Please check the BCRW website and Spring 2020 calendar for forthcoming details.