A Conversation with Gerard Gaskin

A Conversation with Gerard Gaskin

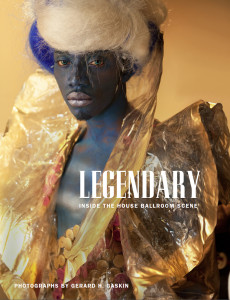

My first encounter with Gerard Gaskin’s photography was the arresting portrait gracing the cover of the Fall 2013 Duke University Press catalog. The image was from the cover of Gaskin’s first book, Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene. I was not surprised to find that Gaskin hailed from a Trinidadian background since that striking image had so much of the carnivalesque in its composition. His connection to the Caribbean and the focus of his work made Gaskin ideal as one of our presenters in the “Gender and the Caribbean Body” public event at the City University of New York in Spring 2014.

A native of Trinidad and Tobago, Gerard H. Gaskin earned a BA in liberal arts from Hunter College in 1994. His photographs have been widely published in newspapers and magazines and have also been featured in solo and group exhibitions across the United States and abroad. His work is featured in the permanent collections at Duke University, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of the City of New York, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Gaskin has garnered much recognition in the form of awards, grants, and residencies, including the New York Foundation for the Arts Artist fellowship for Photography (2002), the Queen Council on the Arts Individual Artists Initiative Award (2005), and the Woodstock Center of Photography Arts-In-Residence (2011). In 2012 he won the CDS/Honickman First Book Prize, which resulted in the publication of Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene (Duke University Press, 2013). The interview below took place via e-mail in Fall 2014.

Kelly Baker Josephs: In a recent interview with Neelika Jayawardane, you describe your current work in very personal terms: “I’m making portraits of Trinidadian artists, and at the same time, I’m learning what it means to be a Trinidadian artist.” Yet, your most-well-known work thus far, Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene, is not identified as Trinidadian in content. How is Trinidad, or a notion of a regional Caribbean, important to your self-identification? How does this extend (if at all) to a consideration of the Caribbean diaspora?

Gerard Gaskin: I am an Afro-Caribbean male born in Trinidad and raised in Queens, NewYork, by two British Caribbean people. They raised me to always love being, and to identify as, a Trinidadian and a Caribbean person. Interestingly, I see myself not as an American but as a black man in America. This is the closest I have come to identifying with an Americanness. Otherwise, I feel that my art is from an English Afro-Caribbean point of view, even when what I am photographing has American content.

Having lived outside of Trinidad for so long, I seek a Pan-Caribbean community. Many of my close friends and artist community have been formed from not just a Caribbean sensibility but a search for a larger collective West Indian identification. I think the example of cricket and my love for it helps to illustrate this. C. L. R. James has argued that cricket played an important role in creating a collective regional identity, and I believe similarly my love for cricket and my art have allowed me to forge and find community through a Caribbeanness. One of my projects is on cricket in the Caribbean, and I take these photographs because the game reflects on regional collaborations.

KBJ: Could you say a bit more about what you mean by the statement, “I feel that my art is from an English Afro-Caribbean point of view”? How do you see your work as connected to this Caribbean (or even specifically Trinidadian) identity?

GG: My teacher at Hunter College, Roy deCarava, told me when I graduated that I should go back and find my Caribbean or my Trinidadian identity because this would make my work stronger. So in 1994 I moved back to Trinidad and I stayed there for about a year. In many ways, this was the beginning of my engaging actively with home and my returning over and over as an adult and artist. Over the years, I have traveled to different places in the Caribbean to expand my understanding of the region. I have been to Cuba, Jamaica, Antigua, and Barbados. In many ways, my work on the house and ballroom communities could not have happened without this exploration. Deborah Willis has commented on how my photography reminds her of Carnival in the Caribbean. I do not think that for many years I was conscious of why balls and their subversions of identity were so interesting to me. It is only later that I realized that it was because they reminded me of how Carnival at home troubled many kinds of identities through performance.

KBJ: Do you feel that artistic representation has the potential or responsibility to “trouble” or transgress traditional understandings of gender?

GG: Yes, I think my photographs work at the intersection of both race and gender. My project on the house and ballroom scene here in the United States is clearly talking about queer poor and working-class people. MMMMy images are always asking, What is a woman or a man, and what is it to be black, white, or Latino? These are the questions my images pose over and over. Since these images are of performances, then my photographs also ask questions about beauty. Are the images beautiful? Are the dancers beautiful? Through different experiences of beauty, my pictures ask you to rethink your gender expectations.

KBJ: Your house and ballroom series seems to me to centralize questions about masculinity. How do you feel your work (in general or one work in particular) represents masculinity? Do you work specifically to transgress traditional notions of masculinity?

GG: One of the images in my book Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene is of a subject in a bright pink skirt with polka dots and a black top. His hair is bleached and he is wearing a veil. The subject has makeup on, but the makeup does not really make him very feminine at all. The makeup, skirt, gloves, handbag, veil, hair accessories, and other objects fail to deliver either a masculine or a feminine subject. Gender performances, through clothing, posture, and makeup, actually highlight how gender is constructed. He is male and female, is a man playing at being a woman, and a man failing to perform gender.

“#6 Martez, Evisu Ball, Harlem, NY, 2005”

KBJ: How is photography, your chosen medium of representation, particularly well suited to your aims of transgression?

GG: Let me try to answer by staying with the same image. The image uses the conventions of documentary photography. Normally, the documentary form is supposed to give you access to the real and true. I use this form but refuse to provide simple access to the real. Instead, I use it to ask what is real.

KBJ: Whom do you envision as the primary audience for your work? In terms of reception, has that audience been different from the population you envisioned? Do either of these (your envisioned audience or your experienced audience) shape your work?

GG: Any artist would like to have as large an audience as possible. My different projects have slightly different audiences. My cricket photographs are aimed at a Caribbean audience; my Lefrak City photographs I hope appeal to a NYC audience; my ball photos are for the ball community and for a middle-class audience who are usually people of color. I think the audience most important in each case is an audience that is connected to and understands the subject matter I am photographing.

KBJ: Does this “connection to” your subject matter mean there is less you feel needs to be “explained” to these audiences? That is, is it important that you contextualize your work? If so, how do you provide this context?

GG: I think the way I do this is by showing my different projects separately. So, I do not generally mix my projects in any one showing. When I show my ball photographs, this is to explore gendered and racialized identities. My Lefrak City images are about race and class in relation to urban housing projects. My Trinidad and Tobago artists project has focused on intense close-up images of Trinbagonian artists to ask questions about the diversity of Trinidad and Tobago identity. I show these projects separately, so that repeated views on a topic can provide some depth and context for my audiences.

KBJ: The images in these projects often walk the fine line between an exploration of the body’s potential and the danger of exploiting the body. How does this distinction function for you (if at all)? How do you maintain the integrity of your work while also respecting those (individuals/communities/nations/regions) you represent?

GG: This is a problem any artist, activist, or scholar faces. How do we think about the integrity of the people we photograph and the bodies we capture? I know no easy answer for this. I am aware that when my book on balls came out, I got the fame and credit for the book. One of the ways I have tried to be sensitive to this is by taking my books to the balls and sharing it with the ball communities whenever I can. Then, whenever I have been interviewed, I have tried to speak in detail about members of the community who have been important to me and the community. This is my way of paying tribute to them. One of the tragedies of the ball community is that many members who used to be important in the 1990s died from HIV/AIDS. I often try to remember them when I speak about the balls. I also give back by photographing for free. This may be for a memorial service, for a ball, for a nonprofit that works with the community. I try to be engaged and part of the activities of the community as my way of giving back.

Kelly Baker Josephs is an associate professor of English at York College, CUNY. Her book Disturbers of the Peace: Representations of Insanity in Anglophone Caribbean Literature (University of Virginia Press, 2013) considers the ubiquity of madmen and madwomen in Caribbean literature between 1959 and 1980. She is the editor of sx salon: a small axe literary platform and manages the Caribbean Commons website.