The Photography of Keisha Scarville

The Photography of Keisha Scarville

Figure 1. Keisha Scarville, Untitled, from the i am here series, 2013. Archival digital print, 24 in. x 24 in. All images courtesy of the artist.

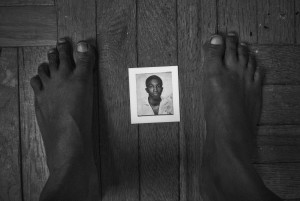

It is a body draped in a white dress, whose shoulders are made bare, whose black skin is illuminated, whose fingers dance and linger in a pool of white salt, whose hand gently cups an old, charred passport photo of a young boy, whose feet border a replica of the same photo, this one not tattered and torn but intact (see figs. 1 and 4–7).

In these selected images from the i am here series by photographer Keisha Scarville, the body is present, though never in full—only in parts. Even with this mosaic of parts, it remains a solitary body immersed in both vulnerability and strength. There is no landscape or other figure to eclipse the body’s presence in the frame, except for a few images in which the body engages with a wood-paneled bedroom floor. The artist shares with me that this suite was created in her Brooklyn bedroom.1 That it was conceived and executed in the space of her home—an interior space, one of intimacy and of privacy—further elevates its elegance and solitary strength. i am here is at its core a relationship with the self.

As the central character, this body, this self is deeply performative in its stoic stances, its poetic gestures, and its rituals of simplicity. i am here is equally about the body as it is about an imaginary space of home. The body here functions as symbol. In the artist’s statement about the genesis and evolution of the series, Scarville focuses not on the body itself but on what the body houses: “A home lives and breathes. It suffers, rejoices, and dies. A home gives us a space to practice freedom and instills in us a sense of belonging in the world. It is a function of memory and imagination. It is both the tangible and the obscure. i am here is a personal journey towards claiming and understanding the conception of a home. In it, I explore rituals and the body as the primary site of belonging.”2

Home is a constant site of artistic engagement and perhaps even angst for Keisha Scarville. She self-defines as Guyanese American. Born in 1975 to a Guyanese father and mother who migrated to the United States in the late 1960s, she spent her childhood in Brooklyn, New York, where she still resides. She will be the first to admit that within the walls of her childhood home, her experience was still a Guyanese-centered one. She is not alone in that sentiment. While this only-English-speaking country in South America has a population of 750,000, there are an estimated 2 million Guyanese citizens living outside its borders in global metropolises like New York City, London, and Toronto.3 In Scarville’s own backyard, the Guyanese community makes up the fifth-largest immigrant group in New York City. Like these denizens of the diaspora, the Scarvilles maintained their connection to Guyana, returning often to their homeland and sustaining deeply embedded cultural rituals and traditions here on American soil.

Over time, Scarville has steeped her work in etching out the tensions this bridge between here and there conjures up. For the many of us who have left one place for another, we know the bittersweet of troubling those waters, of threading dual spaces of birth and of home, and of coming to an understanding that these two are not always one and the same. We also know that when we have left others behind in places that are beautiful yet impoverished, the act of troubling the proverbial waters of identity and belonging is one of privilege.

Of her series Many Waters,4 motivated by a trip she and her mother took back to Guyana and which featured members of her extended family who still live there, she writes of the relationship between the landscape and identity: “There was a need to mend the staggering feeling of displacement. . . . I wanted to capture the tension of returning to a place that was once ‘home’ and then through distance and time, becomes unfamiliar territory.”5

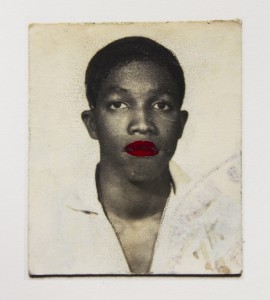

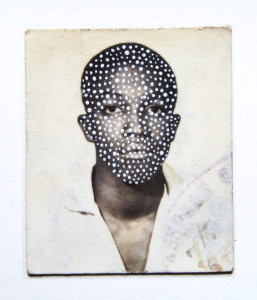

Figures 2 and 3. Keisha Scarville, Untitled, from the Passport series, 2013. Mixed media, 5 in. x 7 in.

Scarville’s oeuvre bears witness to the present as well as looks to the past. While Many Waters rests on present times and mines the emotional remnants of the Scarville family’s sojourns between two Americas, Scarville gazes back to investigate images that already exist in her family history. In her ongoing Passport series, she infuses her artistic practice with her own rich personal archives, transforming the ubiquitous passport photo, namely, a photo of her father in his early teens in then British Guiana,6 into an art object. Her various artistic treatments, over fifty and counting, of this humble five-by-seven-inch archival document, include layering, collaging, distorting, scratching, damaging, and superimposing the portrait with other images.7 In some reiterations, Scarville directly engages, if not violates, the body in the image, rendering her father’s lips a blood red or using whiteout to paint over the eyes or masking the face with a constellation of white dots (figs. 2 and 3). “I was inspired by Romare Bearden,” she writes of the series, “in that I reflected on his ability to build, re-inscribe and transform our relationship to the past by visually dislodging and bringing back together that which is universal.”8 She does this by repeatedly returning to the body in the image, treating it as both canvas and symbol.

What separates the Many Waters and Passport series from i am here are their centering on other bodies. To hear the artist describe the choice to frame her family members as the subject of the series is to hear her reflect on how bodies of color have been historically mis/represented. She tells me that it took time for her to employ her own body as the subject, opting instead to first give that space and presence to her family. This is not solely an artistic gesture on her part as photographer; it is a choice of activism, one that aims to counter a historic malpractice of invisibility, erasure, and censorship. Scarville—daughter of immigrants, woman, woman of color, educator—is acutely aware that this act of insertion of black bodies, Caribbean black bodies, is deeply charged with cultural, political and historical meaning. When she wears her hat as a teacher of photography for institutions such as the Studio Museum of Harlem, the New Museum of Contemporary Art, and the International Center for Photography in New York City (where I interviewed her), she is always conscious of the heavy lifting still needed to position these bodies of work as significant to the history of art as well as to contemporary art: “In thinking about the history of photography, images that I grew up with and images that I absorbed through education, I didn’t see a lot of images that look like my family. For all those reasons, it is extremely important.”

Figure 4. Keisha Scarville, Untitled, from the i am here series, 2013. Archival digital print, 24 in. x 24 in.

i am here marks a notable arc in the artist’s trajectory—Scarville shows up in the frame, cleverly giving the title of the series a literal interpretation. The artist is indeed present. She is both artist as maker and artist as performer. It makes perfect sense that if i am here is at its core a dialogue with the self, then the artist has to face the camera. “When I was looking at this idea of home and who my family was,” Scarville explains, “it was inevitable that I started to look at myself and at where I stood in all of this.” Yet, although the word here in the title emphasizes presence, i am here is ironically more about absence. The artist knows that often what is absent on the page can be more profound than what is present.

Absent is a whole body. Scarville gives only parts of the body the stage. She also ushers in a focus on another sacred identifier of both self and self-ethnography: the skin. In these acts of self-examination, the artist offers up these questions: “How do I define home? Where is that space? Where is that belonging for me? Where do I push that pin that tells me where I am in all of this?”

Absent from the frame is a face. Scarville positions the face out of the frame or shows the body from behind (fig. 1). This is not an act of refusal or of turning away, but one of generosity, allowing viewers to imagine their own selves in the frame. Absent, too, is any clear marker that this body is aiming to represent man or woman. Although it is Scarville’s body, the images are more provocative if we look at them as steeped in gender ambiguities. The artist engages with gender as unfixed and in transition. In these parts of the body—in the silhouette of the back, in the curve of the shoulders, in the strength of the fingers, in the lifelines of the hand, in the solid planting of the feet—coexist harshness and softness, grit and tenderness, the masculine and the feminine.

Figures 5 and 6. Keisha Scarville, Untitled, from the i am here series, 2013. Archival digital print, 24 in. x 24 in.

Absent from the series is color. Scarville has been working in black-and-white photography for most of her career. She tells me it is the aesthetic that best serves her artistic vision, one that feels most natural to her: “My eyes are designed to see everything in black and white. There’s something when black and white is extracted, it lays bare other elements of the frame, other elements of what is happening in the image. That’s what I’ve always gravitated to about back and white: the things that my eyes become extra-sensitive to when I’m not looking at color.”

In the image from i am here in which the artist frames the passport photo of her father between her feet, she is intentional in averting the gaze from the color of the wood of her Brooklyn bedroom floor to the color of skin (fig. 7). The artist’s employment of black and white brings to the surface the connections between the tone of her legs and that of her father’s own skin. The absence of color also activates and merges both time and space—two generations, two homelands, and all the complexities in between. While Scarville negotiates the solid planting of her feet on an American landscape, and a very New York one at that, her father’s passport photo is a reminder that she is also a descendant of bodies born from another soil and of another time. Yet, notice there is no wavering in the artist’s stance. She is rooted firmly in both lands.

Figure 7. Keisha Scarville, Untitled, from the i am here series, 2013. Archival digital print, 36 in. x 24 in.

When the photography on the Caribbean is still dominated by images picturing paradise, when the already vibrant colors of the region are often exaggerated and hyperpigmented to satisfy global appetites for the tropical, when Caribbean black- and brown-skinned bodies continue to be exoticized and hypersexualized, Scarville’s choice not to color the body but to “lay it bare” in black and white extends beyond being countercultural. Instead, it is a counternarrative to what the global public often sees of the visual culture of Guyana and its diaspora, particularly in the photographic image—a gaze that reflects the exotic, the tropical, the colonial, and the touristic. For Scarville, this body of work might possibly function as an act of refusal. She is saying no to the use of this body as a product for consumption.

Like her engagement with her father’s passport photo, Scarville also carves out a connection with her mother via the image of the artist draped in her mother’s white dress (fig. 1). The image evokes a sense of loss and quiet grief and begs us to question, What exactly is being mourned here? Of her construction of this image, one that speaks to the artist’s craft in playing with form, light, and performance, Scarville shares with me, “While I was negotiating and reconciling questions about home, where I see myself or where that place is, my mom came up and this desire of wanting to fit into my mom’s clothes. I borrowed this dress from her. When I put it on it didn’t fit. I hadn’t zipped it up yet. But what I saw was this space, this revealing of my skin against her clothing.”

Perhaps, what the artist is intuiting is a truth about what lies at the heart of her aesthetic vision, about what sustains her practice: what may seem like failure—when the dress does not fit—is instead an opening, a catalyst, for a new kind of breakthrough. It is in this convex, this space of revealing, we uncover ambiguities of the most beautiful kind.

Guyanese-born Grace Aneiza Ali is the founder and editorial director of the award-winning OF NOTE, a magazine centered on art and activism. She is a faculty member in the Department of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at the City College of New York, CUNY, and recipient of the 2014 Outstanding Faculty of the Year Award. Highlights of her curatorial work include the following roles: Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts Curatorial Fellow; guest curator for the 2014 Addis Foto Fest; guest editor of the Fall 2013 Nueva Luz Photographic Journal and author of its critical essay on contemporary Guyanese photography; and host of the Visually Speaking photojournalism series at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center.

1 Keisha Scarville, interview with the author, International Center for Photography, New York, 11 December 2014. Hereafter, unless otherwise cited, all Scarville quotes are from this interview.

2 Keisha Scarville, keishascarville.com/section/89694_i_am_here.html (accessed 15 December 2014).

3 The history of increased migration from Guyana to North America and Europe is due to unstable economic conditions, which continue to prevail—43 percent of the population in Guyana currently lives below the poverty line. Manuel Orozco, “Remitting Back Home and Supporting the Homeland: The Guyanese Community in the US,” Inter-American Dialogue Working Paper, US Agency for International Development GEO Project, 15 January 2003, www.thedialogue.org/PublicationFiles/Remitting%20back%20home%20and%20supporting%20the%20homeland.pdf (accessed 15 December 2014).

4 The title of the series refers to the Amerindian meaning of Guyana—the land of many waters.

5 Keisha Scarville, keishascarville.com/section/17138_Many_Waters.html (accessed 15 December 2014).

6 The country was known as British Guiana before gaining its independence from the British in 1966.

7 Read more about Scarville’s Passport series in Grace Aneiza Ali, “A Guyana Worldview: Photographers Keisha Scarville, Nikki Kahn, Roshini Kempadoo, Sandra Brewster,” Nueva Luz Photographic Journal 17, no. 3 (2013).

8 Scarville, keishascarville.com/section/330661_Passports.html (accessed 15 December 2014).