to

Writing for Coralee

with

What does it mean to write within the silences of history? To write through them and against them?

What does it mean to hold a space where silences can persist as refusal yet not become normalized as erasure or the narratives they could contain not become appropriated?

Coralee Hutchison, the only casualty and probably the youngest victim of the police repression of the 1969 black student protest in Montreal, was always destined to write in her own voice. But this voice was made silent when she died, before she had the chance to publish her own poetry or her thoughts on these events. Her very presence on the ninth floor with the protesters told me that she knew how to raise her voice. The brutality with which a police officer struck her after she defended herself with her words told me that she also knew how to use them.

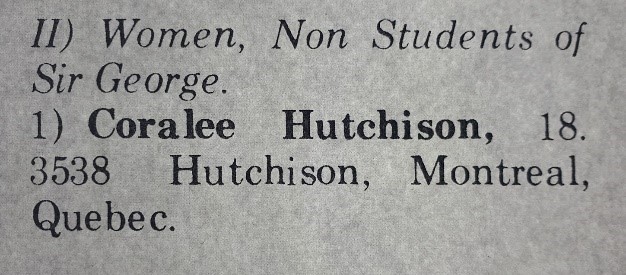

Instead, what is left of her, in the archives, is a name and age as part of a list of people who were involved; what is left is silence and the fading but heavy memories of people who are now older men. Men who knew her and saw what happened to her. Yet the silence is powerful and persistent. There is silence in the archive, silence of her now vanished poetry, unpublished as far as I know; silence knotted with the grief of men who can barely tell her story; even silence of the documents regarding her existence.

Figure 1. Excerpt from “A Breakdown” (a list of all persons arrested on the ninth floor of Sir George Williams University, 1969), The Paper, 17 February 1969. Source: Concordia University Records Management and Archives

I first learned about Coralee while doing a life-story interview with Philippe Fils-Aimé, one of the participants in the student protest, in an effort to record memories of the events of 1969 at what is now Concordia University, in Montreal.1 Philippe was the perfect interviewee and more than willing to share the complexities of his life story and activism between Haiti, the United States, and Quebec. He is a voluble, engaging, and passionate narrator, and despite having witnessed and experienced exile, arrest, loss of family and friends, and violence to diverse repressive regimes,2 despite having lived through the police violence of February 1969 at Sir George, he remains a joyful and optimistic presence.

Except when it comes to Coralee.

He knew her, you see. Not a lot, but enough to have been to her place and for her to read her poems to him. After a few hours, in the middle of the interview, Philippe suddenly evoked Coralee, and for the first time he cried. He cried not for himself but for her young, delicate spirit, full of light and promise, a spirit worried about the intricacies of language through poetry, and for her life abruptly interrupted because of a fatal blow to the head. The policeman had hit her hard, Philippe recalled, because he had said something vile to her and she had answered back. And she died from that blow, he was sure, several months later, discretely and unseen. Who could imagine such a beautiful being killed by an act so senseless and brutal? Just the recollection of this event made Philippe cry and broke his narrative apart. We had to stop to change the tape, and it was a necessary time to stop, filled with emotion. But then, a few days later, this short part of the interview was inexplicably lost, accidentally erased from the recording. As if this story would not stay in the archive, whatever we did. It went back to erasure, or maybe it was made for silence.

There is silence in literature as well as history, I have found.3 On the shores of catastrophe, a lot of great literary texts opt for inscribing versions of silence within the texture of the writing, in one form or another. Writing, then, becomes an exploration of silence. This initial reflection led me to devise a research-creation project with the oral history archive of Haitian immigrants in Montreal, under the title “Thinking from/in the Place of Silence.” I wondered about the im/possibilities of writing with the narrative of survivors of violence and what it meant to do so. I have found that, for me, only the poetic form, what it evokes and embodies, can occupy this place because it manages to include silence in its fold, to start from a place where a new language has to be created.4 Only the poem can mobilize language to create a space where both silence and meaning, the unknown and intention, can coexist to provide a form of restitution, unpredictable, opaque.5 Only the poem can restore language to new elaborations instead of investing it with the fixity of death, restore it to humanity instead of dehumanization, to coincidence of voice without subterfuge or substitution. It is a place of profound intersubjectivity achieved only by an authentic identification with an absent voice, legitimized by the commonality of experience rooted in ancestry and continued in the present through new iterations, achieved by listening profoundly and intently, not as mere performance, but instead inventing another level of subjectivity that acknowledges presence and absence, what is known and what has to stay in the dark. A subjectivity of proximity, and of coincidence, that can recognize the absent voice and give it a way to become supported if not embodied through the risk of writing. It is a voice that is singular yet plural because it is profoundly personal, but still it manifests the density of silences and the voice that is missing into existence. Therefore, it denies death by refusing its erasure and fixity, by continuing the missing voice, in its presence and its absence, both unbearable and powerful. Only through traces can this thought exist poetically, transforming the finite materiality of the/my body into the continuous presence of creation.

I wrote this poem for / with / to Coralee Hutchison because I remember a time when I, too, believed in poetry and justice in an absolute way. I, too, thought that being in a university would allow me to live these truths.

Today, Coralee Hutchison is dead, and I am alive and almost reasonable. Still at the university, still writing poetry, but still looking for knowledge and justice.

I wanted to think about how a place can aspire to represent knowledge and still exert power, still instrumentalize bodies, certain bodies, of course, more than others, like holes on a computer card to be punched and pinned to the ground, open for all to see and allow with this void for the machine to be fed, to devour, to prosper.

How dare these unforeseen black bodies break our wonderful machines, they thought. How dare they not play along, not know their place, by wanting to be doctors and exist in our world? How dare they want to occupy this space on their terms? And Coralee, how dare she answer the police officer and write poetry and read it out loud on her bed?

She invited people into her world, after all. You could tell she was so young, looking to be broken, maybe looking to die.

I, on the other hand, wanted to speak to her, not in her place but in dialogue and, maybe, with her as a small continuation of her. I could see her so clearly, wanting to be the “I” she read in her books or, even better, the silent person beyond the page of the books, the one who, with some authority, wrote “I.”

Grown men still cry today about the promise of her life and the waste of her death. Me, I cannot cry so much anymore because too many of us are dead. Besides, I teach tomorrow. So instead of dying, I write today, instead of crying over deaths that concern me.

I leave only my voice, the materiality of my body for her to have a breath through these cords, something audible that concerns both of us, a trace of her presence, a place for her to stay on the pages, where she wanted to be.

Some ghosts belong to us.

I accept to be haunted.

—Montreal, 15 December 2019

Writer, painter, and scholar Stéphane Martelly is a professor of creative writing and research-creation in the Literature Department of the Université de Sherbrooke and an affiliate professor in the Theatre Department at Concordia University. She was born in Port-au-Prince and now lives in Montreal. She has published poetry (La boîte noire suivi de dépars [Écrits des Hautes Terres/CIDIHCA, 2004]) and children’s tales (Couleur de rue [Hachette-Deschamps/Edicef, 1999]; and L’homme aux cheveux de fougère [Soleil de Minuit, 2002]). Her pictorial work is showcased in the digital art book Folie passée à la chaux vive (Madness Spent in Quicklime) (Publie.net, 2010). She is the author of a monograph on Haitian poet Magloire-Saint-Aude (Le sujet opaque [L’Harmattan, 2001]) and several articles on Caribbean literature. Her latest work on research-creation is Les jeux du dissemblable: Folie, marge et féminin en littérature haïtienne contemporaine (Nota Bene, 2016), and other recent publications include La maman qui s’absentait (Vents d’Ailleurs, 2011), Inventaires (Triptyque, 2016), and L’enfant gazelle (Remue-Ménage, 2018).

1. Philippe Fils-Aimé, life-story interview with Stéphane Martelly, December 2018, Montreal Life Stories: Haiti Working Group, Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling (COHDS), Concordia University, Montreal; see http://storytelling.concordia.ca/sites/default/files/COHDS%20Archives%20Holdings%20Overview%20Dec%202019.pdf.

2. Philippe left Haiti during the Duvalier regime, only to experience both racism and civil rights resistance in the United States and in Canada.

3. See Stéphane Martelly, Les jeux du dissemblable: Folie, marge et féminin en littérature haïtienne contemporaine (Montreal: Nota Bene, 2016).

4. See Audre Lorde, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde (1984; repr., Berkeley: Crossing, 2007), 36–39.

5. See Édouard Glissant, Traité du Tout-monde (Paris: Gallimard, 1997).