Kaie Kellough’s Dominoes at the Crossroads includes two stories—“Shooting the General” and “Ashes and Juju”—that reference the antiracism student protest in 1969 Montreal that became known as the Sir George Williams affair.1 This discussion will focus almost exclusively on these stories, which, like the others in the collection, offer a window onto the theme of black exclusion from Montreal’s—and by extension Canada’s—dominant (i.e., white) society. It is worth noting here that it was practices of racial exclusion—in this instance, a professor’s disqualifying grades for black students, to prevent them from entering medical school—that resulted in the historical occupation of the Sir George Williams University computer center.2 A central question subtends the drama and cogitation that comprise these stories: How do blacks respond to the servile roles that a majority-white society seeks to force them into? Conjointly with the enslavement of Africans came the ideology, foundational to Western colonialism, that Africans were subhuman, hence inferior to Europeans, and best suited for brute labor. The first of Kellough’s epigraphs in Dominoes at the Crossroads, taken from Aimé Césaire’s “Depuis Elam. Depuis Akkad. Depuis Sumer,” vividly captures the European figuration of African peoples as beasts of burden:

J’ai porté le corps du commandant. J’ai porté le chemin de fer du commandant. J’ai porté la locomotive du commandant, le coton du commandant. J’ai porté sur ma tête laineuse qui se passe si bien de coussinet Dieu, la machine, la route.3 (9)

Inasmuch as epigraphs function to provide a frame for the text, the two epigraphs that open Dominoes at the Crossroad alert us to the author’s intention to explore the complex question of race in Montreal (Canadian) society. The first reads like Césaire’s contestation of Rudyard Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden” (a poem that depicts non-Europeans as half-devil and half-child).4 The second is taken from an interview with Maryse Condé:

Simply, a Caribbean story could not really be told without reference to servants. Don’t forget that, after all, as a black person, I descend from the slaves, and the slaves were always silent, forced to be silent. They knew they were the real masters of the island.5 (9)

In beginning with these epigraphs, Kellough offers a nod to a Caribbean Antillean literary tradition for his stories geographically set in Montreal. Kellough arguably narrates Montreal as a crossroads of the black diaspora. This can also be seen in the fact that Hamidou, the narrator in both stories, is a Senegalese Canadian, whose initial existence is as a very marginal character in Hubert Aquin’s Prochaine épisode.6 Kellough’s extensive reinvention of Hamidou is in essence a dialogic exercise that transforms the merely nominal character into a three-dimensional being. One is reminded of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart as a corrective response to Joyce Cary’s Mister Johnson, a novel that reflects the caricatured European view of Africans in their relationship to colonial “masters.”7 In Dominoes at the Crossroads, Kellough engages profoundly with African Canadian ontology and history and treats the Sir George Williams affair as a seminal moment in that history. More specifically, his use of both epigraphs evokes the existential condition of blacks in the West and foreshadows the heightened awareness of Kellough’s characters about the servile roles they are expected to play.

The first story of the collection, “La question ordinaire et extraordinaire,” alerts us to the fact that these stories will be framed by history. “La question” is written as a lecture, delivered a hundred and fifty years hence by Kellough’s great-grandson, about Montreal in the early twenty-first century (i.e., present-day Montreal). “[Kaie Kellough] saw the way Black histories were constructed as minor narratives and as narratives that ran counter to official Québec histories,” the lecturer-narrator explains. “This allowed for the suppression and minimization of the contributions of Black Quebeckers to Québec culture, and for an erasure of their historical presence” (12). The rest of the story details the imaginary future time of the lecture, when Montreal is renamed Milieu and has no dominant racial majority that is able to marginalize others. In this future time, Marie-Joseph Angélique, the slave who in 1734 allegedly set fire to her mistress’s house and burned down a considerable part of Montreal, is now venerated as one of the ancestors of the city—a stark contrast to 2017 when the publicity undertaken to commemorate the 375th anniversary of Montreal excluded all people of color.8

Now to the Sir George Williams affair, which occurred in February 1969. A cursory perusal of discussions about the affair at the fiftieth anniversary commemoration shows that it has profoundly imprinted Canadian history, supporting David Austin’s implicit claim in Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex, and Security in Sixties Montreal that the “affair” was perhaps the most significant university student protest in Canada: “Not just the largest student occupation in Canadian history, but internationally the most destructive (to property) act of civil disobedience on a university campus.”9 Beyond the journalistic pieces contemporaneous with the occupation, the affair has been parsed in Dorothy Eber’s 1969 The Computer Centre Party: Canada Meets Black Power, which Dennis Forsythe describes in his 1971 Let the Niggers Burn! The Sir George Williams University Affair and Its Caribbean Aftermath as “a fairly honest [but incomplete] journalistic account”; in several essays, a significant number of which appear in Forsythe’s Let the Niggers Burn!; in Austin’s 2013 Fear of a Black Nation; and in the 2015 documentary The Ninth Floor, comprised of interviews with some of the participants as well as television footage.10

Fictional treatments of the Sir George Williams affair have, however, been scant. Right after the event came Peter Desbarats’s 1970 play The Great White Computer.11 My rhetorical use of the Sir George Williams affair in my 2001 Behind the Face of Winter faintly echoes the racist sentiments I heard on the bus and the metro and on the radio in Montreal during the computer center occupation and the court trials that followed. Many of these comments implied that blacks did not belong in the university, that the destruction of the computers was proof that they were impervious to the blessings of civilization, that in essence they were and would remain Calibans. My character Trevor Erskine in Behind the Face of Winter employs the incident to educate fourteen-year-old Pedro, who has just arrived in Canada from the Caribbean, about how Euro-Canadians perceive blacks—that is, that blacks are expected to occupy servile, poorly remunerated employment and are discouraged from and even punished for aspiring otherwise.12 Most recently, in 2019 the affair is commented on briefly by Gary Freeman’s Prez, the protagonist of Exile Blues.13 Also in 2019, Tableau D’Hôte Theatre staged the play Blackout to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the protests.

Kellough’s stories “Shooting the General” and “Ashes and Juju” can be combined for analysis; the first serves as a preface for the second. Our first encounter with Hamidou is similar to meeting people for the first time and listening to them reveal themselves hesitantly and selectively. We learn that he is Senegalese (as he is in Aquin’s Prochaine épisode) and that he first worked as a spy for the Senegalese government and then for the Quebec government. In “Shooting,” he has just returned to Montreal from France, where, as an undercover agent, he failed in his mission to steal the painting The Death of General Wolfe. He is also addicted to amphetamines and opiates, ostensibly to help him maintain the psychological demeanor required of a successful spy. On the day of the actual destruction of the Sir George computer center and the arrest of the students occupying it, Hamidou passes by the Hall Building, observing the falling computer punch cards thrown from the ninth floor and hearing the chant, “Let the niggers burn!” He clearly knows the issues that have led to this catastrophe, but he is not the typical heroic black character that one associates with the black liberation epoch of the 1960s and ‘70s. He is not a Huey Newton, Bobby Seale, Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Stokely Carmichael, or Walter Rodney—people who sacrificed their safety and in some cases their lives battling for justice and civil rights for blacks in the United States and in the newly independent countries of Africa and the Caribbean. As an infiltrator for the police and by extension the government, Hamidou collaborates in the oppression of blacks.

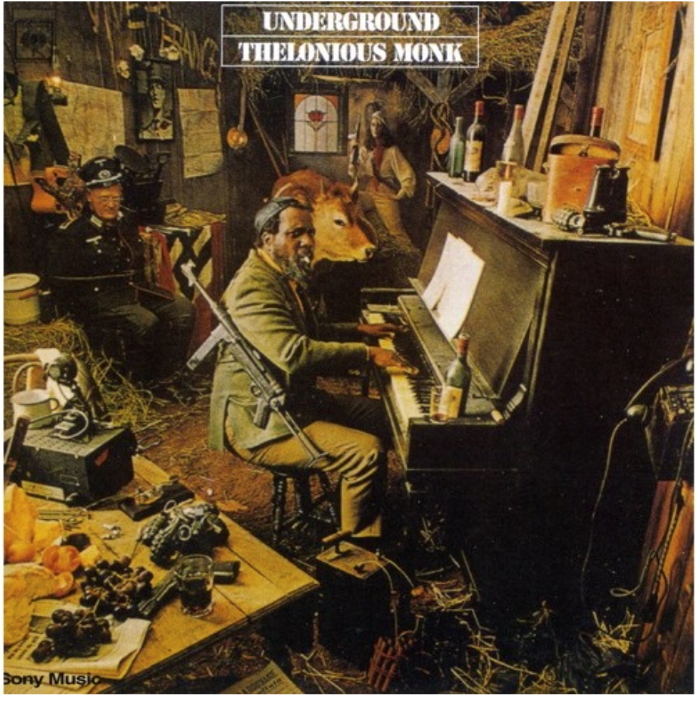

Given that the protesting students might well asphyxiate in the computer center, which is on fire when Hamidou walks by the building, it jolts the reader to next find Hamidou descending into the Peel metro station and thinking not of the students who might be dying in the fire but of the painting on the record cover of Thelonius Monk’s 1968 Underground. In part of Hamidou’s reflection, he vividly describes the cover’s scene and mood: “The room looks like a cross between a barn and cellar with straw and hay littered across the floor boards, bottles of wine standing on various surfaces, a store of grenades on a table. Monk, surprised mid-song, smoking, has a dynamite detonator at his feet” (41). Additional images include a bound Nazi SS officer, a woman holding a machine gun, and the graffiti “Vive la France.” These are disturbing images of entrapment that fuse the bestial and artistic, the racist and his victim-foe. The images evoke liberation, even if it results in suicide. The stated-unstated is, I will have freedom or we will all die. The painting reflects what campaigners for civil rights in the United States were saying at the time. It also parallels the unfolding of the Sir George Williams affair in its culmination in fire. What started as an abuse of power by a racist professor, who is supported by his white colleagues, leads to a sit-in and protest in the computer center, which is now barricaded and on fire. It also shows us that at this stage Hamidou is attracted to art that reflects his dilemma, but he is unprepared or unwilling to explore it.

Figure 1: Underground by Thelonious Monk, record album cover, 1968.

It is while reflecting on the album cover that Hamidou comes upon the sign “FOR RENT/À LOUER” and discovers what he believes is his comfort zone. The sign—characteristic of Montreal’s two dominant languages—gives him a sense of spatial security because he has just returned from a failed mission in Paris, a lieu he does not know. “FOR RENT/À LOUER,” however, also characterizes who he is, how he has until now earned his living: he rents himself out—for spy missions, mainly, and in one case to steal art. But arrival at his comfort zone might merely mean that he has come to some sort of self-acceptance and an understanding of and a resignation to his place in Montreal society. Bathos best describes what is happening to him; it is in terms of escape from indignity but also from reality that he describes his new existence underground.

But what Hamidou recounts in “Shooting the General” is mostly surface reality and half-facts. In “Ashes and Juju,” we will learn the full facts that he cannot escape. First, it is worth casting a cursory dialogic glance at how the underground has functioned in literature. It is a trope that Homer, Dante, Dostoyevsky, Ralph Ellison, and Richard Wright and even I, to name a few authors, have employed. The underground is where protagonists go when the solutions they seek cannot be found in the everyday world or when the quest for truth or understanding stalls, leaving them in crisis. Some protagonists emerge from it enlightened with truths to share. Some, however, remain there to escape from a world they find overwhelming. The latter is Hamidou’s case.

Yet Hamidou’s escape from the tribulations of the above-ground world is not altogether successful. It can be argued that by the time he enters the underground, his spy persona has already supplanted his authentic self, and it is to regain that self that he goes underground. His decision is of course unconscious. Underground, he transitions from being a literal double-agent who spies on blacks for the police and the government to a seller of African art. And in so doing, he no longer earns his living working for people who despise blacks. But even so he is alienated from his cultural roots, and he is indifferent at best to what is taking place in the community. He is only able to acknowledge this indirectly—through his understanding that the objets d’art that he sells have no meaning outside their cultural context. He becomes obsessed with wanting to make a film about the Sir George Williams University protest but knows that this is a delusion. And at every anniversary of the affair, for all thirteen days that the students occupied the computer center, he is haunted by nightmares that intensify and attain their acme on the thirteenth day. The reason for these nightmares is that the police had engaged him to spy on the students, to incite them to destroy property, and to even set fire to the computer center. This aspect of Hamidou’s portrait evokes the historical fact that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police had spies in all the black movements in Canada before, during, and after the actual Sir George Williams affair.14 Hamidou’s nightmares are a reprise of the acts he had been engaged to carry out. To his credit, he deliberately bungled his mission, and in so doing, did not altogether betray the students. But by allowing himself to be a tool of the police, the enforcers of oppression, and to be the target of their racist jokes in the process, he sacrificed something vital to his dignity and his psyche.

His recurring nightmares and his obsession with making the film point to guilt arising from self-betrayal, guilt that he needs to expiate. Unless he can resolve what is haunting him, “he will be forever trapped inside [his] vertiginous narrative” (169). Moreover, his fears and obsession leave him sleep-deprived and even cause him to hallucinate. We are to understand that Hamidou’s moving to the underground, a form of hiding, was his attempt to brush aside his past. But his past defies him, and his attempt to repress it threatens his sanity. He therefore recalls the past, confronting it not in the form of a film but as memory, as story. For Kellough’s narrative purpose, Hamidou’s act of speaking the truth into the hollow cavity of the sculpture of an elephant suffices as an end to the story. But it is difficult to see how this will bring about the expiation that Hamidou seeks, for it is yet another way of repressing his feelings of guilt. It may well be, however, that for certain transgressions, containment is the most that the transgressor can hope for.

As Lawrence Hill opines of incorporating African Canadian history into fiction, “[It] is one way of showing people who we are.”15 More important is our incorporation of that history into fiction as a way of understanding ourselves and the forces that restrict or seek to restrict us. The racism that was contested with explosive results at Sir George Williams University in 1969 is a centerpiece of that history. Kellough’s fictional treatment of it gives us a great deal to reflect on and might well make us examine ourselves to see whether we are accomplices in our own oppression.

H. Nigel Thomas was born in St. Vincent and the Grenadines and moved to Montreal in 1968. From 1976 to 1988 he was a teacher with the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal, and from 1988 to 2006 a professor at Université Laval. He is the author of several essays in literary criticism and eleven books: the novels Spirits in the Dark (House of Anansi, 1987), Behind the Face of Winter (TSAR, 2001) (in French as De glace et d’ombre, trans. Christophe Bernard and Yara El-Ghadban [Mémoire d’encrier, 2016]), Return to Arcadia (TSAR, 2007), No Safeguards (Guernica, 2015), and Fate’s Instruments (Guernica, 2018); the short fiction collections How Loud Can the Village Cock Crow, and Other Stories (Afo, 1995), Lives: Whole and Otherwise (TSAR, 2010) (in French as Des vies cassées, trans. Alexie Doucet [Mémoire d’encrier, 2013]; finalist for the 2016 Prix Carbet des lycéens), and When the Bottom Falls Out, and Other Stories (TSAR, 2014); and the literary criticism From Folklore to Fiction: A Study of Folk Heroes and Rituals in the Black American Novel (Greenwood, 1988) and Why We Write: Conversations with African Canadian Poets and Novelists (TSAR, 2006). In 1994 and 2015 he was nominated for the Hugh MacLennan Fiction Prize, and in 2000 he received the Jackie Robinson Award for Professional of the Year from the Montreal Black Business and Professional Association and in 2013 received the Université Laval’s Hommage aux créateurs. He is the founder of Lectures Logos Readings and is its English-language coordinator.

1. Kaie Kellough, Dominoes at the Crossroads (Montreal: Vehicule, 2020); hereafter cited in the text.

2. As told to the author by Alfie Roberts, who coordinated much of the solidarity support the occupying students received. Roberts expresses similar views in A View of Freedom: Alfie Roberts Speaks on the Caribbean, Cricket, Montreal, and C. L. R James, ed David Austin (Montreal: Alfie Roberts Institute, 2005), 79–80.

3. Aimé Césaire, “Depuis Elam. Depuis Akkad. Depuis Sumer,” in Soleil cou coupé (Paris: K, 1948), 67 (“I have carried the commandant’s body. I have carried the commandant’s railroad. I have carried the commandant’s locomotive, the commandant’s cotton. I have carried on my nappy head that gets along just fine without a little cushion God, the machine, the road”; Aimé Césaire, “All the Way from Akkad from Elam from Sumer,” in The Complete Poetry of Aimé Césaire, bilingual edition, trans. A. James Arnold and Clayton Eshleman [Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2017], 399).

4. Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden,” 1899, http://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poems_burden.htm.

5. Maryse Condé, quoted in “Maryse Condé by Rebecca Wolff,” Bomb, no. 68 (July 1999), https://bombmagazine.org/articles/maryse-cond%C3%A9/.

6. See Hubert Aquin, Next Episode, trans. Sheila Fischman (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2010), 17. Originally published as Prochaine épisode (Montreal: Cercle du Livre de France, 1965).

7. Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart (1959; repr., New York: Fawcett, 1969); Joyce Cary, Mister Johnson (1939; repr., New York: New Directions, 1989).

8. For one account of the story of Angélique, see Afua Cooper, The Hanging of Angélique (Toronto: Harper Collins, 2006). On the 2017 publicity, see, for example, “Organizer Apologizes after Ad for Montreal’s 375th Features only White People,” CBC News, 22 November 2016,

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/montreal-375th-anniversary-ad-c….

9. David Austin, Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex, and Security in Sixties Montreal (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2013), 137.

10. Dorothy Eber, The Computer Centre Party: Canada Meets Black Power (Montreal: Tundra, 1969); Dennis Forsythe, preface to Dennis Forsythe, ed., Let the Niggers Burn! The Sir George Williams University Affair and Its Caribbean Aftermath (1971; repr., Montreal: Black Rose, 2019), 3. In particular, LeRoi Butcher’s “The Anderson Affair,” in Forsythe, Let the Niggers Burn!, 76–110. Austin, Fear of a Black Nation, 138–42. Mina Shum, dir., The Ninth Floor (National Film Board of Canada, 2015), https://www.nfb.ca/film/ninth_floor/.

11. See Dennis Forsythe, “By Way of Introduction: The Sir George Williams Affair,” in Forsythe, Let the Niggers Burn!, 8.

12. See H. Nigel Thomas, Behind the Face of Winter (Toronto: TSAR, 2001).

13. See Douglas Gary Freeman, Exile Blues (Montreal: Baraka, 2019). In Freeman’s narrative, Prez and some of his friends were outside supporting the students. Prez’s account of who did what reflects the blame game—the police blaming the students for the destruction, the students blaming the police (61–62).

14. See Austin, Fear of a Black Nation, 155–56.

15. Lawrence Hill, quoted in H. Nigel Thomas, ed., Why We Write: Conversations with African Canadian Poets and Novelists (Toronto: TSAR, 2006), 135.