This art piece arises out of Rachel Mordecai’s spring 2021 “Caribbean Family Sagas” seminar at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Students were assigned the reading of Jan Lowe Shinebourne’s The Last Ship, which follows three generations of a Chinese family living in Guyana.1 Much of the novel centers on the Chung family’s matriarch: Clarice Chung. During my reading, one aspect of the novel that struck me was Clarice Chung’s insistence on Chinese blood purity, which is a stark contrast from my own experiences growing up Jamaican Chinese. Thus this scroll attempts to articulate the limits of this type of racial categorization for those living in societies that are increasingly creole and those who are themselves mixed race (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Grayson Chong, Threads of Fate (full view), 2021. Acrylic paint and thread on cotton, 27 × 10 in. All photographs by the author/artist.

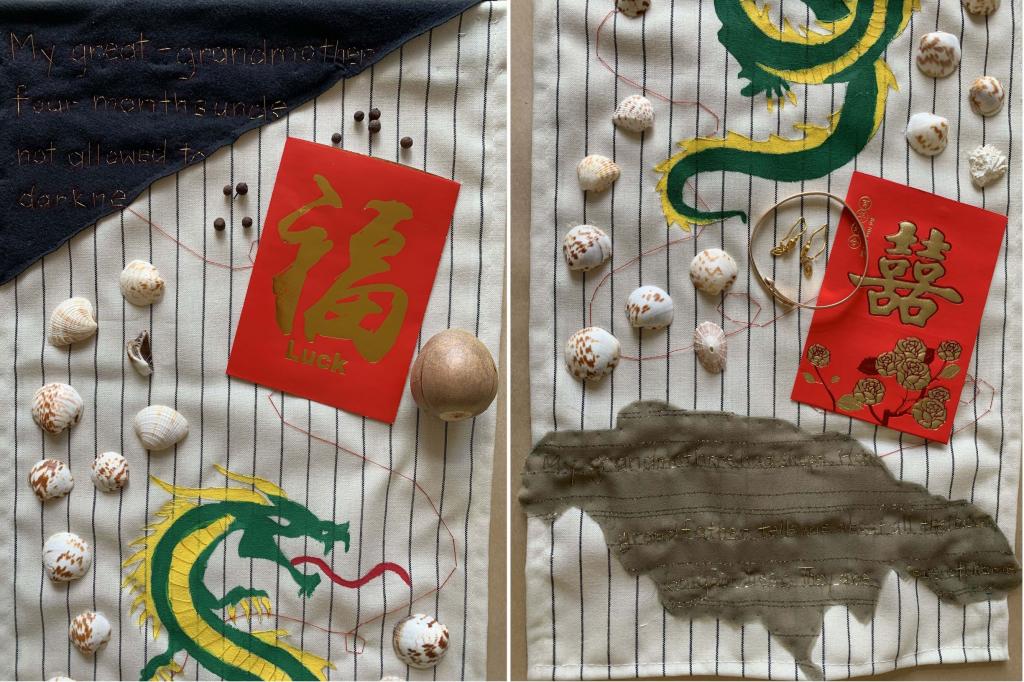

This scroll contains one perspective of the Jamaican Chinese experience. I have embroidered pieces of my family history into the cloth. The first narrative is that of Loy Keow Chin (my paternal great-grandmother), told to me by Gene Chong (née Wong; my paternal grandmother). It is supposed to read: “My great-grandmother left China for Jamaica, never to return. She spent four months under the ship in the cargo hold. They were not allowed to come up on the deck. Four months on the ship. Only darkness.” For practical purposes, the letters are embroidered in gold so that the story can be read clearly. This stands in contrast to the second narrative that focuses on the experiences of my grandparents living in Jamaica: “My grandmothers had shops. Hard work. Hard work. My grandfather tells me about all the colours of his bougainvilleas. They are a piece of home.” The gold letters blend into the island of Jamaica to represent how my family have become integrated into the social and cultural fabric of Jamaica. Certain parts of sentences are fragmented and missing to articulate the limits of what parts of (family) history are known and what remains hidden or unrecoverable due to the passing of time (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Grayson Chong, Threads of Fate (top and bottom).

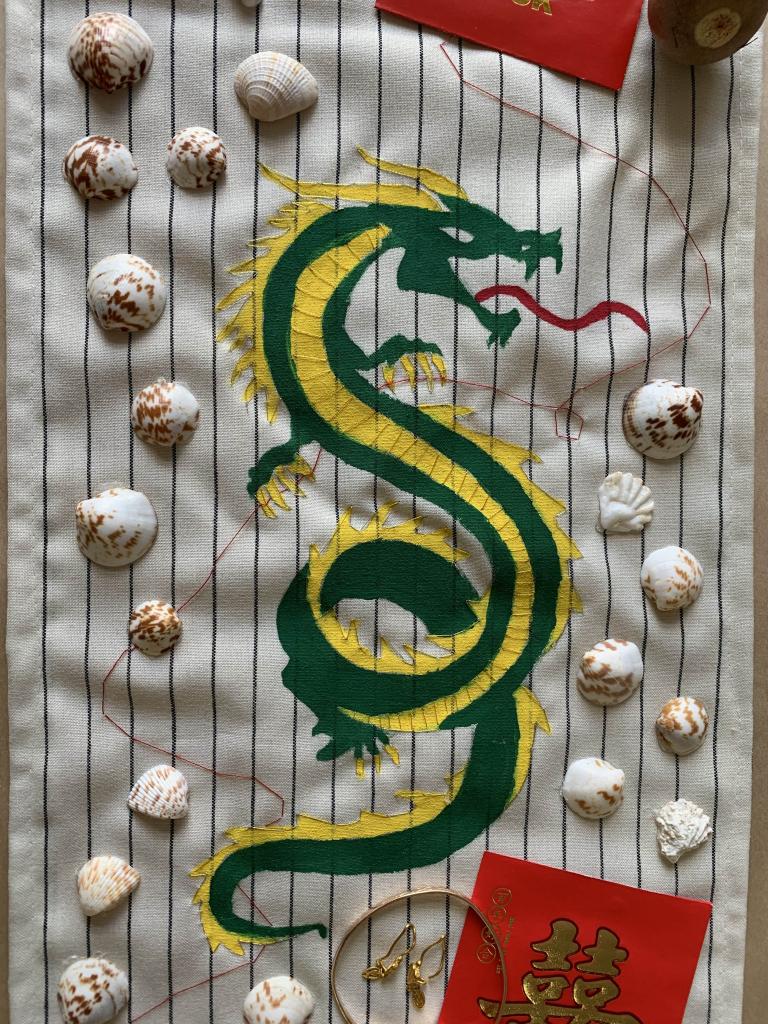

In The Last Ship, Clarice shows her son a yellowing scroll depicting her ancestor, Emperor Chengzong, wearing a yellow dragon coat. She also has pouches containing silver coins, soya bean seeds, and seeds of the plum tree that grew near their house in Hong Kong.2 I substitute the yellow dragon for a green one so that the dragon’s body stands out against the neutral color of the cotton fabric. The red pocket envelopes on the scroll are inspired by Clarice’s pouches. Traditionally, money in the red pocket envelopes signals the accumulation of financial capital and the Jamaican Chinese community’s reputation as shopkeepers. Instead of money, these envelopes contain an avocado seed, pimento seeds, and jewelry. In the novel, Clarice’s daughters-in-law (Mary and Lily) watch as the family eat a Chinese soup. Ironically, Mary and Lily are Chinese, but they are not full Chinese, barring them from partaking in this “Chinese ritual for Chinese people.”3 The avocado and pimento seeds attempt to subvert this ritual and demonstrate how food becomes an expression of creolization. The seeds I chose become a stand-in to represent mixed Chinese Caribbean peoples. The second envelope includes jewelry that once belonged to my ancestors, to symbolize a kind of ancestral capital and remnants of their existence when there is no documentation left of them or any way to point to lineage. In short, family heirlooms become another way of documenting and tracing genealogy and kinship as they are passed down between various family members and generations. In addition, I added seashells from Jamaica along the sides of the scroll. As well as being included for aesthetic purposes, the shells represent an “accumulation of sediments” of family history through fragmented narratives (fig. 3).4

Figure 3. Grayson Chong, Threads of Fate (dragon).

Finally, there is a Chinese belief that an invisible red thread connects lovers or those who are destined to meet. No matter how far apart or how knotted the thread becomes, it will never break. In many ways, I see Jamaica and China as two lovers. Given my own positionality, one is not without the other; they exist simultaneously. For me, living in the Caribbean diaspora, the invisible red thread connects me to Jamaica and China; no matter where I am in the world, I am connected to these two geographies. Ultimately, this art piece highlights the multiple stories of family and kinship that thread culture, history, and identity together.

Grayson Chong is a transhistorical Caribbeanist and doctoral student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. As an artist-scholar, she creates visual art to explore the intersections of music, performance, and (most recently) fashion and fabric in the Caribbean. Her research uses transhistorical, postcolonial, and diasporic approaches to investigate how familial kinship and womanhood are expressed in visual and musical performances within Jamaica and the Caribbean diaspora. Her recent article, “Hurricanes and Headpieces: Storytelling from the Ruin and Remains in Caribbean History and Culture,” is featured in Comparative Media Arts Journal, issue 9 (2021).

[1] Jan Lowe Shinebourne, The Last Ship (Leeds: Peepal Tree, 2015), 66–67.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 63.

[4] See Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 33.