The plumbing of black cultural innovations reaches beyond our modern discussion of appropriation. Black cultural elements that were deemed fashionable or practical were selectively appropriated by wider white colonial society from as early as the eighteenth century. It appears that white women throughout the French Atlantic, including south Louisiana, the Caribbean, and metropolitan France, adopted the Afro-diasporic tradition of head wrapping. What appear to be headwraps in a handful of portraits of white women in southern Louisiana were most likely borrowed from women of color in the region who innovated the style. Both women of color and white women shared a creole culture rooted in unequal power relations that resulted in white women’s adopting and paring down styling techniques like headwraps, use of madras, copious metallic jewelry, and white cotton chemises.

In an 1808 letter, Leonora Sansay describes Pauline Bonaparte, the wife of General Charles Leclerc—whom Napoleon Bonaparte sent to Haiti in 1801 to stanch the Haitian Revolution—as adopting the manner and dress of women of color: “She . . . is rendered interesting by an air of languor which spreads itself over her whole frame. She was dressed in a muslin morning gown, with a Madras handkerchief on her head.”1 The passage evokes the listless glamor that was associated with white creoles. The white creoles of the Directoire were valorized for their thinness, pallor, and sickly yet lusty dispositions.2 The self-styling of women like Josephine de Beauharnais, Marie Antoinette, and Pauline Bonaparte are central to understanding uneven cross-pollination (and appropriation) between white and Afro-descended women.

Figure 1. Costume Parisien, “Chapeau de Velours, orné de deux Plumes. Collier en esclavage. Théâtre Italien.” Plate 76 from the Journal des dames et des modes, 1798. From the digital project Style Revolution, created by Alex Gil, Anne Higonnet, et al., 2017. © The Morgan Library and Museum, New York

A fashion plate of a woman wearing a “collier en esclavage” appeared in the Paris-based Journal des dames et des modes in 1798 (fig. 1). A favorite accessory in Empire-era French fashion, “bondage collars” often described necklaces of three interconnected pendants of cameos or semiprecious stones. The necklace drawn here, however, is a more simplistic version that is akin to actual chains. Given that enslaved people and free people of color in Saint Domingue (and throughout the Atlantic basin) were in the process of fighting for greater freedom, it is hard not to believe that here “esclavage” is a reference to chattel slavery.

The taste for lightweight white fabrics was also brought back to the metropole. One of Marie Antoinette's favorite ensembles was the gaulle (or later chemise à la reine), a white muslin shift that her dressmaker Rose Bertin adopted from white creole women in the West Indies—who, in turn, adopted these garments from women of color.3 The chemise à la reine morphed into simpler, loose gowns often paired with lightly woven shawls, neat fichus, and the simple hairstyles à la créole inspired by a coterie of tastemaker merveilleuses who included Pauline Bonaparte, Fortunée Hamelin, and future empress Joséphine de Beauharnais. Joséphine and her ilk’s penchant for muslins and headkerchiefs was often associated with their birth and upbringing in the Antilles.4 Though the tubular shifts were said to have harkened back to classical silhouettes in a moment of Greco-Roman mania, there are numerous direct references to its origin in the Caribbean, as woven cotton textiles were more practical in the tropical heat. There continues to be a celebration of créolité as a distinct aspect of the Caribbean among intellectual and cultural producers; however, it is clear that this “creolization,” or mimicry of creole culture, was playing out in the metropoles too, as seen in the public self-styling of bourgeois white women who had appropriated styles from free and enslaved women of African descent in the colonies.5

Figure 2. Agostino Brunias, Linen Day, Roseau, Dominica—A Market Scene, c.1780; oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The headwraps and loose gauzy shifts worn by the women in Agostino Brunias’s painting Linen Day, Roseau, Dominica—A Market Scene, for example, and appropriated by white women from the planter class, were influenced by African antecedents (fig. 2). Although traditions of head wrapping can be encountered globally, West Africa is well known for producing elaborate head coverings worn by both men and women:

Headscarves (headwraps), worn casually as well as for special occasions, were popular among women throughout West Africa. This form of headdress varied in style and pattern depending on the circumstances. Headscarves were functional in that they enabled women to balance loads on their heads, protected newly styled hair and made one “presentable” when in haste.6

Although they are called different names in different regions—geles in Nigeria, for example—headwraps were and remain integral to dress practices across Africa.

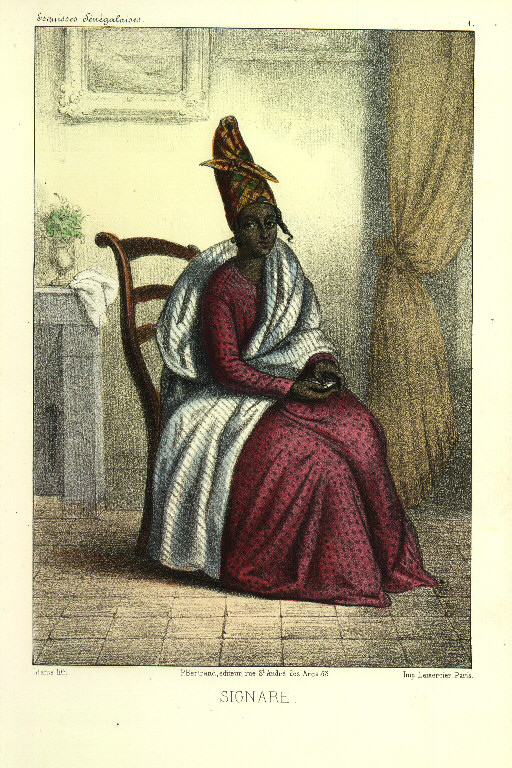

Helen Bradley Griebel and John K. Thornton both argue that the West African coast was a site of intense cultural exchange, and the headwrap is product of this cross-pollination, especially given that there is no evidence that West African peoples were wrapping their heads with woven fabrics prior to European contact.7 On the islands of Saint-Louis and Gorée, off the coast of present-day Senegal, headwraps were central to the self-styling of signares, a class of mixed-race women who reigned over these islands and wielded economic power through commercial networks and interests in the transatlantic slave trade. As the progeny of several generations of concubinage between African women and European men, signares used their connections with white men to their advantage. Travel writers described these women as expressing power through their elegant self-presentation, most notably their headdresses. In 1789, Antoine-Edmé Pruneau de Pommegorge, who spent twenty-two years in West Africa as a merchant, described the signares’ headwraps as follows: “They wear a very artistically arranged white handkerchief on the head, over which they affix a small narrow black ribbon, or a colored one, around their head.”8 He also described them as wearing the same white muslin shifts that we see in the Caribbean Basin and that were popularized by the merveilleuses. According to historian George E. Brooks, the white handkerchief headwrap would evolve into a “striking cone-shaped turban, artfully constructed with as many as nine colored handkerchiefs,” becoming “the hallmark of signares in Senegal and The Gambia.”9 In an engraving that accompanies the 1789 travel account of Dominique Harcourt Lamiral, a servant’s head and chest are uncovered, while a signare is draped in white fabric and topped with a headwrap.10 In an 1853 illustration in L’abbé David Boilat’s Esquisses sénégalaises, a signare is drawn in a conical headdress of what appears to be madras, a fabric used in Afro-diasporic head wrapping throughout the Atlantic basin (fig. 3).11

Figure 3. Jacques-François Llanta, Femme du Sénégal: Signare, ca. 1853; lithograph. Plate 1 from L’abbé David Boilat’s Esquisses sénégalaises (1853). Bibliothèque nationale de France

Signares were often paid in gold, which they turned into jewelry and used to buy clothing “because they adore, as do women everywhere else, fashionable clothing,” according to Pruneau de Pommegorge.12 Brooks, writing almost two hundred years later, found that many of the early accounts “continue[d] to be relevant” in Senegal: “Senegalese women still possessed an unrivaled flair for displaying clothing, jewelry, and other finery. Or de Galam (gold from Galam) is still the byword for quality and purity.”13 The wearing of abundant metallic jewelry is a practice that spread to the Western Hemisphere among Afro-descended women in the Caribbean and the rest of the Americas.

West Africa also has a rich tradition of woven fabrics that was augmented by contact with European colonizers, which resulted in imports of textiles from Europe and Asia. The West African coast was a space of hybridity where the elite flaunted their consumptive power through the collecting and display of locally made and foreign textiles.

European goods and access to them came to mark free African women's status, defining elite African womanhood on the coast. The cotton pagnes, madras cloth transported from India, became symbols of distinction as women used them to create elaborate mouchoirs de tête (headwraps). These conical formations, derived from traditions of adornment already in circulation in the Senegal delta, became the distinguishing feature of the late eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century signare. Women also draped multiple pagnes around their bodies in displays of wealth and conspicuous consumption, and as acts of beautification.14

Images of signares of Saint-Louis (in present-day Senegal), for example, show them decked out in towering headwraps, dripping in gold jewelry, and draped in sumptuous white muslins. Many scholars have posited that the taste for brilliantly white gowns—first appropriated by Marie Antoinette and the so-called merveilleuse and soon after adopted by many fashionable women across France and Britain—was first innovated by women of color in the Caribbean and West Africa.15

Historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall notes that “two-thirds of the slaves brought to Louisiana by the French slave trade came from Senegambia.”16 The prevalence of enslaved people from the Senegambia facilitated cohesion among Louisiana’s black population. Moreover, the accelerated rate of this population’s creolization resulted in a longer retention of shared cultural values from the region. Sophie White writes,

There are no explicit references in Louisiana’s records to the retention by blacks of africanisms in their dress and appearance. However, echoes of shared West African aesthetics can be detected, and in Louisiana may have included an emphasis on the head, adornment with certain kinds of metallic and non-metallic jewelry and ornaments, or the prevalence of certain colors, such as red, popular across a spectrum of Senegambian nations.17

Beth Fowkes Tobin also posits that headwraps and metallic jewelry were African retentions: “The African Caribbean use of brightly colored cloth (red in particular), the prevalence of gold and semiprecious stones in jewelry, as well as the turbaned headdresses that both men and women wore reflected African styles and tastes in clothing.”18 The penchant for red textiles that Tobin notes may be a reference to the Vodou deity Erzulie. Erzulie, who presides over matters of love, beauty, and adornment, is often associated with the color red. The red elements in the outfits of women of African descent in images and portraits from the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French Caribbean may have origins in Yoruba-derived Afro-diasporic belief systems. Or it may have simply been the go-to color for expressing luxury and sumptuous pleasure in one’s own body.

When enslaved Africans arrived in the New World, they were forced to shed—and sometimes forgot about—many cultural elements; at the same time, many held on to cultural traditions from the African continent, giving them new meaning in the New World context. One of these traditions was the headwrap, which enslaved Africans carried across the Atlantic from the Senegambia to Louisiana, for use as a practical as well as a beautifying accessory. Though it is a syncretic accessory that mixed woven fabrics produced in Europe and Asia with West African aesthetic values, it was almost universally recognized as a defining characteristic for African and Afro-diasporic dress by the eighteenth century and up to the present day.

Despite its association with women of color, white women were clearly inspired by Afro-diasporic head wrapping, though this cultural mimesis was not reciprocal. If one considers the numerous portraits from the early nineteenth century of French and white creole women in headwraps, it is clear that there was a decades-long trend in wearing colorfully printed headwraps, incorporating madras accessories into wardrobes, and other subtle styling techniques inspired by free and enslaved women of color. These elite white women appropriated sartorial innovations from women of color with whom they often shared intimate spaces. These styles were even taken to metropolitan France, inspiring a trend in creolized aesthetics that obliquely referenced exoticized colonial possessions. This ping-pong match between African and Afro-diasporic styling techniques, on the one hand, and Europeanized textiles like madras, on the other, was not even-keeled. Black women did not always have the liberty and resources to dabble freely in Euro-American sartorial traditions, especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Yet black women since the eighteenth century have consistently managed to overcome the predations on their unique cultural self-expression to make the headwrap a mainstay of African and Afro-diasporic dress practices.

Jonathan Michael Square is a writer, historian, and curator specializing in fashion and visual culture of the African diaspora. He is an assistant professor of Black Visual Culture at Parsons School of Design. This year, he also holds a joint appointment as a fellow in the History of Art and Visual Culture at the Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. His writing has appeared in The Fashion Studies Journal, Vestoj, Guernica, Hyperallergic, British Art Studies, and the International Journal of Fashion Studies. A proponent of the power of social media as a platform for radical pedagogy, he founded and runs the digital humanities project Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom, which explores the intersection of fashion and slavery.

[1] Leonora Sansay, Secret History; or, The Horrors of St. Domingo and Laura, ed. Michael J. Drexler (Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview, 2007), 64.

[2] See Amelia Rauser, The Age of Undress: Art, Fashion, and the Classical Ideal in the 1970s (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 139–45.

[3] See Michael Batterberry and Ariane Ruskin Batterberry, Mirror, Mirror: A Social History of Fashion (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977), 190; Stella Blum, Eighteenth-Century French Fashion Plates in Full Color: 64 Engravings from the “Galerie des Modes,” 1778–1787 (Mineola, NY: Dover, 1982), 29; Aileen Ribeiro, Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe, 1715–1789 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 227–28; and Caroline Weber, Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution (New York: Holt, 2006), 150.

[4] For an example of Joséphine wearing a headwrap à la créole, see Michel Garnier’s Portrait of Josephine de Beauharnais (1790), Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame, sniteartmuseum.nd.edu/collections/european (accessed 4 June 2021); see also Andrea Stuart, The Rose of Martinique: A Life of Napoleon’s Josephine (New York: Grove, 2003), 163–65, 191–92.

[5] In 1989, Patrick Chamoiseau, Jean Bernabé, and Raphaël Confiant published Eloge de la créolité as a response to the perceived inadequacies of the négritude movement. The term créolité attempted to describe the cultural and linguistic heterogeneity of the Antilles and, more specifically, of the French Caribbean. Maryse Condé was one of the first scholars to level a critique against this male-dominated literary movement and complicated their definition of creolization; see Maryse Condé, “Order, Disorder, Freedom, and the West Indian Writer,” Yale French Studies, no. 97 (2000): 151–65. Since then, others such as Gisèle Pineau and Shalini Puri have complicated the idea of créolité and think more carefully about power and cultural exchange in the Caribbean.

[6] Steeve O. Buckridge, The Language of Dress: Resistance and Accommodation in Jamaica, 1760–1890 (Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2004), 23–24.

[7] See Helen Bradley Griebel, “The West African Origin of the African-American Headwrap,” in Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time, ed. Joanne E. Eicher (Oxford: Berg, 1995), 207–26; and John K. Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 233.

[8] Antoine-Edmé Pruneau de Pommegorge, Description de la Nigritie (Amsterdam, 1789); quoted in George E. Brooks Jr., “The Signares of Saint-Louis and Gorée: Women Entrepreneurs in Eighteenth-Century Senegal,” in Nancy J. Hafkin and Edna G. Bay, eds., Women in Africa: Studies in Social and Economic Change (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1976), 24 (Brooks’s translation).

[9] Brooks, “Signares of Saint-Louis,” 25.

[10] Dominique Harcourt Lamiral, L’Afrique et le peuple affriquain [sic], considérés sous tous leurs rapports avec notre commerce et nos colonies (Paris : Dessenne, 1789), 81.

[11] Femme du Sénégal: Signare, by Jacques-François Llanta, in L’abbé David Boilat, Esquisses sénégalaise: Physionomie du pays, peuplades, commerce, religions, passé et avenir, récits et légendes (Paris: Bertrand, 1853), plate 1.

[12] Pruneau de Pommegorge, quoted in Brooks, “Signares of Saint-Louis,” 24 (Brooks’s translation).

[13] Brooks, ibid., 25. A recent exhibition at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Good as Gold: Fashioning Senegalese Women (24 October 2018 to 2 February 2020), explored the rich tradition of the use of gold adornment among Senegalese women.

[14] Jessica Marie Johnson, Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 29.

[15] See Rauser, Age of Undress; and Philippe Halbert, “Creole Comforts and French Connections: A Case Study in Caribbean Dress,” The Junto: A Group Blog of Early American History, 11 September 2018, earlyamericanists.com/2018/09/11/creole-comforts-and-french-connections-a-case-study-in-caribbean-dress.

[16] Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth-Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 29.

[17] Sophie White, “‘Wearing Three or Four Handkerchiefs around His Collar, and Elsewhere about Him’: Slaves’ Constructions of Masculinity and Ethnicity in French Colonial New Orleans,” Gender and History 15, no. 3 (2004): 549.

[18] Beth Fowkes Tobin, Picturing Imperial Power: Colonial Subjects in Eighteenth-Century British Painting (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999), 158. The term African retention was coined by anthropologist Melville J. Herskovits to describe African cultural traits that survive among people of African descent in the New World. Debates surrounding the degree of Africanness have been foundational for the study of the black presence in the Americas. For a full exegesis of the concept, see Melville J. Herskovits, The Myth of the Negro Past (Boston: Beacon, 1990). For a debate on whether headwraps are of African provenance, see Helen Bradley Foster, New Raiments of Self: African American Clothing in the Antebellum South (New York: Berg, 1997), 275–81.