For Lorna Goodison

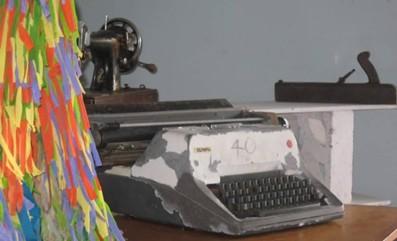

Image: Artefacts of a Near Life. Used by permission of the author

Even the blind, sorrowful poet is written

by his own hand, and he does not know what he makes,

what he will leave behind. — Kwame Dawes, unHistory: A Poem Cycle

That time when we were ibises. — Dionne Brand, “Nomenclature for the Time Being”

i. Bob Marley came to me

Bob Marley came to me

on a bus in Barbados

when a historian friend gifted me a cassette

of the music: Catch a Fire (1973), with hypnotic

Concrete Jungle, Slave Driver,

Stir it up, Kinky reggae,

and all those skanking anthems we loved

and loved to, that still move the soles of our memory

to get up, stand up, in the skin of your heart’s soul,

to make “reggae aesthetic” the beat of your line,

your faith—even though I ’n’ I choose another Christ,

but still chant the same prophetic fire against Babylon.

ii. like, no more light, no more shadow

like, no more light, no more shadow

no more petals changing color

on the drying Rose of Sharon shrub,

no more sliver of a moon

as cycles phase around your calendar?

but there was some body with its scanning life

though now censers perfume holy books,

there was a voice enshrined in metaphor, simile

and art as spare in fine detail as Hasui,

though now the stylish mortician arranges hearsing—

and those living seeds eulogized in the brown earth

will enchant those who find their embracing branches in time.

iii. you would mark 1967–1979 . . .

you would mark 1967–1979 as cornerstone years of the chapel you are,

that brought you to this path winding above the multilane highway

rushing through your century’s violent Vanity Fair:

first bank job, arts, writers, drama crowd you admired,

women who loved you, stroking your gifts,

then to university, literature studies, those you loved forever,

temples of theater and poetry, publishing your first poems and the highs

that went with all that life; home again to teach, direct plays, write columns,

take up your love for radio, spinning Marley, Burning Spear, Kadans, broadcasting

the revolutionary fervor of those times, to first marriage, to Rasta,

then, somehow, your childhood faith finds you, immerses you below waters

and look you now, trodding this track above Babylon’s broad troubled road.

iv. what was that ritual about?

what was that ritual about? On many Old Year’s Nights,

after he had smoked the house with various incenses,

including asafoetida and its pungent aroma,

he would place the clay Choiseul coalpot

middle of our bare front room, fan its charcoal

to glowing red stones, sprinkle on more fragrant powders,

call me to stand in front that local brazier, then motion

to jump over it, back again, and forward one more time—

was that when he whispered intensely into my face “the first born

belongs to the LORD!?” Don’t think he offered any audible ancient invocation . . .

never forgotten, I never knew what that was about. Some initiation perhaps . . .

into the mystery of preacher, priest, poet . . . into this solitary business?

v. you come again to favorite passages

you come again to favorite passages and pathways

in poems, essays, scripture,

to be startled again, to wonder, past comprehension,

the reels of word, their cinematography, delicate woodblock certainty,

insistent calligraphy of measured geometry, certain truths,

“all flesh is grass,” irrefutable revelation, allegorical hermeneutic,

incredible clarity, evangelistic declarations (even under agnostic parasols)—

shafts of sacramental light across encroaching shadows, covenanting

words, darting quick like small birds at the slant of your eyes,

or leaving a sharp tang like tamarind on the tip of your tongue,

and how alarming is the stubborn rhythm of day,

as you look up into its falling shades, its silence, its nodding leaves . . .

vi. today, the clanging, moaning, whining yellow backhoe

today, the clanging, moaning, whining yellow backhoe

is gouging ground, like the metallic dinosaur

it is; it assaults that grove of tall trees

where fireflies signaled at nights, where

crickets loudly clattered without discord, over which hawks

slid on the cool air of this hill, and I

mourn the death of those elegant, mythical trees—

since we moved here, many groves have been supplanted

by concrete houses, their multicolored metal roofs,

rough tracks of roads, loud-speakered cars,

by our necessary domiciles, our relentless weed-whackers—

I miss the semaphore of fireflies under leaves in early night.

vii. art and poems are sacraments of faith

art and poems are sacraments of faith—

the invisible numinous taking shape in our dimension

like angels come from mystery

to paint lines in ink or acrylic, gouache, classic tempera

on our cracked palimpsests, to carve fonts in typeface

immersing impossible words impossibly articulating

the sacred we sense, reach for, avoid—

faith is its own sacrament

bread raised above the cup of our desperate hope

chanting light against demonic doubts and fears of dark

lifting canticles of defiant joy

into metaphors, images of art, of poetry.

viii. this impasto of a world, of a life

this impasto of a world, of a life

on the worn boxed canvas of nothing, nihilo,

sculptural moulding of palate knife

into organic reality of fauna, flora, passion,

the rainbow spectra of brush-strokes

refracting light off lavender hills, blue roofs, white shrouds

of Gaza—no complacent, idle sketch this of unbelief

or safely-galleried, fashionable flat-world icon,

but many-dimensioned mysteries are here,

fire-dragoned as volcanoes, furious as hurricanes, splitting earth’s faults,

murderous as gang vendettas and garden betrayals,

lovely, desirable, maddening—this beautiful, marbled impasto of earth.

ix. the haloed moon, like a portal

the haloed moon, like a portal

to gnostic fantasies of the 7 seraphic messengers

coming and going through apocrypha, the rainbow-

haloed full moon seems apocalyptic, urgent

in its fixed intensity over our callous unheeding,

rushing at each other, divided

from ourselves at the soul, genocidal

across contested borders, autocratic within—

how can there not come a flood of fire

pouring through that halo, giant icebergs falling

out of the red sun, darkness tumbling

like demonic comets on this reeling globe of a fractious world?

x. once, when I was a Rasta

once, when I was a Rasta

I met Christ in a ghetto shack

in the Graveyard off Chaussée Rd, Castries—

with complacent ease of our shared chalice,

him quiet in the circling murmur of chat,

locks falling around his bowed head, brown-

complexioned, deep in itation, he

was the manifest image from memories of art,

messianic, epiphanic, there—

his name was actually Lord, Kenny Lord. He died some time ago.

I still remember that projection, the man, earth-brown floor,

that mystery of desire for the Risen, Hidden One.

xi. tomorrow is not so much uncertain

tomorrow is not so much uncertain

as unpromised /

the day after always comes

turning through monotonous time

or tumbling down past eternity’s veiled apprehensions /

- the infinite mystery of that dessicated, beautiful leaf, look! /

and why has one loved you, so simply,

so forever, faithful to whatever conjunction

of zodiac plotted your coordinates? /

not death, you say, but dying, terrifies,

that decrepit collapsing of a life into the heaped dust of its corners /

I believe in the place where fallen birds, lost cats, encompassing embraces go /

xii. in diurnal journals

in diurnal journals

oracles and omens, ambiguous, obscure

symbolic gestures, eulogies,

mantras of vocalists masked

in ekphrastic correspondences,

and you playing voyeur among the lines

of tattooed goddesses flaunting their bodies

through gossiping sidewalks,

in non-thematic trajectories

at the flirtatious edges of seawater,

or paused, before, bloody white shrouds, of Gaza—

flirtations, eulogies, omens, oracles in our diurnal journals.

John Robert Lee is a Saint Lucian writer. He is the author of Belmont Portfolio: Poems (Peepal Tree Press, 2023) and After Poems, Psalms (Peepal Tree Press, forthcoming). This poem, “Twelve,” is from a new manuscript titled “Diary.”