Viewing Mont Pelée after Katrina and the Haiti Earthquake

Viewing Mont Pelée after Katrina and the Haiti Earthquake

Au bout du petit matin, sur cette plus fragile épaisseur de terre que dépasse de facon humiliante son grandiose avenir—les volcans éclaront, l’eau nue emportera les taches mûres du soleil et il ne restera plus qu’un bouillonnement tiède picoré d’oiseaux marins—la plage des songes et l’insené reveil

(At the end of the wee hours, on this very fragile earth thickness exceeded in a humiliating way by its grandiose future—the volcanoes will explode, the naked water will bear away the ripe sun stains and nothing will be left but a tepid bubbling pecked at by sea birds—the beach of dreams and insane awakenings)

—Aimé Césaire, Cahier d’un retour au pays natal

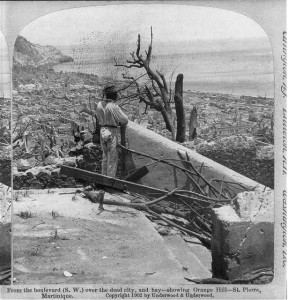

The opening pages of Aimé Césaire’s classic poem are usually read as an evocation of alienated Caribbean subjectivity, angry and warped by three centuries of French colonialism, but the lines from the epigraph above also work as an objective description of the devastation that occurred in and around the Martinican city of St. Pierre on 8 May 1902.1 After several weeks of escalating subterranean noise, fumaroles, noxious sulphur smells, seismic tremors, and waves of poisonous insects and snakes descending from the mountain’s upper reaches, and following a series of lahars, or boiling mudflows, that occurred between 3:00 and 5:00 a.m. (the wee hours), the southwestern side of Mont Pelée blew away just before 8:00 a.m., releasing a massive cloud of incendiary gas, ash, and rocks that descended on St. Pierre. The nuée ardente, or scalding cloud, known scientifically as a pyroclastic flow, instantly killed all but 2 of the 28,000 people located there. The natural and built environments were obliterated in an area of twenty-two square miles, and ships in the harbor ignited as they were engulfed by the fireball that rushed over the water with the speed of hurricane-force winds. First responders were not able to enter St. Pierre for more than seven hours. The scene, recorded immediately in photographs and stereographs (see fig. 1), resembled a no man’s land flattened by WWI shelling, or the site of a nuclear bomb blast. Nothing left, indeed, but Césaire’s “tepid bubbling pecked at by sea birds.”

Figure 1. After the volcanic eruption of Mount Pelée, Martinique, 1902: From the Boulevard (S.W.) over the dead city, and bay—showing Orange Hill—St. Pierre, Martinique, by Underwood and Underwood, 1902. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004680426/.

Eruptions continued throughout the summer of 1902, eventually displacing thousands and claiming more than thirty thousand lives, making this event the deadliest-ever instance of volcanic activity in the hemisphere. Arguably, the massive death toll had been an avoidable, manmade calamity due to the fact that local officials downplayed the threat of an eruption and urged people to stay in St. Pierre in order to participate in an election that had been scheduled for 11 May.

Looking today at pictures of refugees displaced by the violent eruption, it is impossible to avoid viewing the images with more recent regional climatic disasters in mind: Hurricane Katrina’s catastrophic impact on New Orleans and the surrounding Gulf Coast in 2005, and the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. We can begin to develop this comparative perspective by asking, What sorts of political vectors are converging in these images? For example, four days after the eruption, the New York Times cites an appeal by no less an authority than US president Theodore Roosevelt, at whose request Congress appropriated $200,000 in emergency assistance “for the purpose of rescuing and succoring the people who are in peril and threatened with starvation.”2

This seemingly pure philanthropic concern can be interrogated from several angles. St. Pierre, the city obliterated by the volcano, was the financial center and major port for French trade in sugar, produce (especially bananas), and rum. Harper’s had sent Lafcadio Hearn to Martinique in the late 1880s partly to generate interest in investment opportunities through his popular travel sketches. Such writing ably prepared a US reading public to view Martinique within a larger perspective of mare nostrum and annexationist designs on the Caribbean Basin. The US government might have moved to take over Martinique and Guadeloupe, as it did Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Spanish American War, if the volcano had not destroyed St. Pierre as an economic center. Yet, philanthropic-charitable aid—particularly when carried out at the request of a French government unable to intervene effectively in the immediate aftermath of the eruption—can be seen as a softer form of imperial flexing as the ascendant power receives the baton of agency from an empire in decline.

The images under review function as commodities for sale as news and archival data points documenting the flow of imperial history, but also as emotionally charged images with the power to inspire charitable contributions in support of relief efforts. In this regard, what stands out even more starkly to 2013 eyes is the linkage between documentary photos and the idea that disaster relief has increasingly become big business after Katrina in 2005, the Asian tsunamis in 2004 and 2011, and Haiti’s catastrophic hurricanes and flooding in 2008 and earthquake in 2010. Naomi Klein has documented the rise of what she terms a “disaster capitalism complex,” founded in the neoliberal ideas of Milton Friedman and perfected through four decades of violently imposed “privatization” campaigns.3 Against this backdrop of neoliberal globalization, Klein’s analysis reveals how so-called natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina become further occasions for private companies to secure lucrative contracts funded with public money and charitable donations.4 While the scale has increased massively since 1902, we can see the pattern in place even then, with the images of devastation and displacement creating a mobilizing focus point of pathos, moral justification, and saleable commodity.

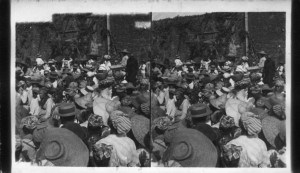

Figure 2. Distributing Relief Supplies to Mont Pelée Refugees, before the City Hall, Fort de France, Martinique, by Underwood and Underwood, 1902. Courtesy of the Keystone-Mast Collection; University of California, Riverside; California Museum of Photography.

On a more immediate gut-response level, images of the 1902 refugees from Mont Pelée, particularly larger crowd shots, evoke similar images from more recent tragedies. Figure 2 shows food being dispersed in Fort-de-France, and immediately reminded coauthor Paulette Richards of scenes outside Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) offices following her evacuation from New Orleans in August 2005. In Jackson, Mississippi, the line for the FEMA assistance stretched around the coliseum, looking like old engravings of people receiving rations from the Freedman’s Bureau.5 Post-Katrina reporting, meanwhile, shows evidence of similar lines outside other FEMA offices.6 A few weeks later, Paulette filled out a FEMA application for assistance on her brother’s computer and submitted it online, receiving the full amount available by electronic transfer into her bank account a few days later. The people who stood in those lines in Jackson, in contrast, were often hassled by clerks who refused to approve them for the full amount available and processed the paperwork at a snail’s pace. Many evacuees also did not have a stable address where FEMA checks could be mailed. In other words, there was a stark class divide in how relief was distributed and in the media representation of who was receiving (or in need of) aid.

The crowd scenes from 1902 also invite comparison with similar images emerging from Haiti in the days following the 12 January 2010 earthquake. Apart from the photos of pancake-flat buildings and the national cathedral ruins that looked like Dresden after the 1945 Allied firebombing, the visuals that probably made the most impact were of a large, hungry, and restive crowd at a food distribution point in Cité Soleil.7 The Haitian crowd shots echo group images from 1902 such as figure 2, but we also found some important contrasts, including a different ratio of women to men. In one photo of the Cité Soleil crowd captured by Los Angeles Times photographer Carolyn Cole, we see an overwhelmingly male crowd (though at the pressure points where food is being distributed, the cameras focused on individual women who had collapsed from heat and the crush of bodies). The force of this masculinized image can evoke a rereading of the classic Bob Marley line, “A hungry man is an angry man,” from an angle that brings out the gendered dynamics of underdevelopment. In the Mont Pelée photos, women dominate the images of St. Pierre refugees, producing a feminization of the tragedy that conveys victimization and pathos.

Perhaps more significant, the 1902 images strongly suggest that the Martinican refugees were a mostly rural population on the move, whereas the 2010 event in Haiti occurred in, and primarily (though not, as we shall see, entirely) impacted residents of, a major urban zone. Without question, the twenty-eight thousand fatalities in 1902 were concentrated in an urban space, St. Pierre, but the refugees depicted in the visual documents are peasants from the countryside. The examination of visual data such as the street traffic in figure 3 led us into some extended reflections about what happened to the Caribbean peasantry between 1902 and 2010.

Figure 3. Fleeing for Life: Mont Pelé Eruption, Martinique, by Underwood and Underwood, 1902. Courtesy of the Keystone-Mast Collection; University of California, Riverside; California Museum of Photography.

Patrick Bellegarde-Smith is one of many commentators who have pointed out that both Hurricane Katrina and the Haiti earthquake were natural events but manmade disasters.8 A key determinant in Haiti’s catastrophic manmade outcome is the way neoliberal dynamics forced people off the land and into Port-au-Prince: off the land through policies ranging from the violent suppression of rural resistance to the US marine invasion of 1915—the so-called Kako Revolt—to the reintroduction of the corvée, or chain gang, to expand rail penetration into the Haitian interior and finally to the clear-cutting of old-growth mahogany and other hardwood trees in the 1920s and 1930s. Interestingly for the cultural critic, these corporate deforestation events are minimized in North American scholarship,9 but they register quite clearly in literary and artistic expressions, in novels such as Marie Chauvet’s Amour, which depicts an American lumber company manager directing clear-cutting operations, and canvases by painters such as Ernst Prophète, who depicts the processing of lumber for export in Trafic de Campêche.10

During the timeframe for neoliberalism outlined by Naomi Klein, German sociologist Maria Mies, and journalist Jonathan Katz, among others, Haitian peasants have been on the receiving end of many neoliberal masterstrokes, such as the decimation of the Kreyol pig population in the 1980s, forced tariff reductions that undercut and destroyed Haitian rice production in the 1990s, and, most recently, the debacle in managing postearthquake relief.11 It is also true that Haiti has for centuries been a kind of proving ground for global capital pitted against a poor but resistant peasantry.12 Off the land and into the city because that was the only place transnational companies opted to locate textile factories. Against this backdrop, it is no surprise that the devastation was concentrated in Port-au-Prince, along with the attention of disaster relief, media focus, and the resulting visuals.

Figure 4. Haitian earthquake refugees landing in Jeremie. Courtesy of Renate Schneider.

Besides making us think about what longue-durée macroeconomic forces impacted rural Caribbean populations between 1902 and 2010, the strong peasant representation in the earlier photographs also prompted a reflection on the less-well-known impact of the Haiti earthquake on rural populations and infrastructure. Despite the urban concentration in Port-au-Prince, Haiti is still approximately 60 percent rural. Economist Mats Lundahl reported that six hundred thousand relocated to the countryside following the earthquake, and some estimates put that number as high as seven hundred fifty thousand.13 Figure 4 shows the Trois Rivières, a freight ship that normally carries produce and goods to and from Port-au-Prince, arriving in the provincial capital of Jeremie. Sent by Renate Schneider, a colleague working at the University of Nouvelle Grand’Anse (UNOGA) outside Jeremie, there is a striking visual correlation between the Trois Rivières photo and figure 5, a 1902 image of refugees arriving in St. Lucia.

Figure 5. Landing of refugees at St. Lucia, by W. G. Cooper, 1902. Courtesy of Southern Methodist University, Central Universities Libraries.

According to Schneider and other UNOGA colleagues, peasant households in Haiti’s Grand’Anse province doubled and tripled in the wake of the refugee arrivals. Closer to Port-au-Prince, rural communities between Leogâne and Jacmel also suffered extreme direct impacts from the earthquake, though this was typically overlooked in light of the overwhelming emphasis on urban devastation. Friends and colleagues in the Fondwa area reported near-total destruction of infrastructure, including the collapse of a community center, primary-secondary school, and university organized by the Peasant Association of Fondwa. Amenold Pierre, who conducted research with coauthor Kevin Meehan for a National Science Foundation–funded grant on the use of mobile communication devices for disaster relief and interagency coordination, reported that people in Fondwa, which is in the mountains south of Leogâne, immediately shifted from concrete to wood in their rebuilding efforts.14

In wrapping up our reflection on the meaning of the 1902 images for viewers in 2013, we also thought about artistic expressions that came out of the hurricane and earthquake experiences and were generated by those who lived through the events firsthand as opposed to those who depicted them from the outside. “Under the Rubble,” by Frantz Zephirin, is one of several postearthquake artworks featured in the September, 2010 volume of Smithsonian magazine.15 Zephirin uses the symbolism of a huge spider web to convey the horror, urgency, and panic of people trapped under collapsed buildings after the earthquake. At the same time, the open eyes and mouths suggest an active struggle for survival, and agency in the broadest sense.

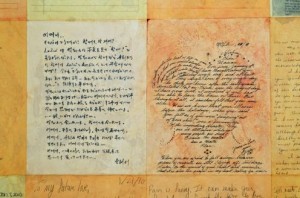

New Orleanean artist Rashida Ferdinand has responded to the impact of Hurricane Katrina in a range of media, including metal, ceramic, papier mâche, found objects, ground spices, and clay. In Love Letters, an installation exhibited at Hammond House in West End Atlanta (fig. 6), Ferdinand reclaims the spaces devastated by flooding in the Lower Ninth Ward by photocopying, onto hand-dyed paper letters, written by her grandmother that describe the earlier flooding of New Orleans after Hurricane Betsy in 1965.

Figure 6. Rashida Ferdinand, Love Letters (detail), 2008. Photocopy on hand-dyed paper, various sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

Like Zephirin’s painting, Ferdinand’s artworks celebrate the human agency of those who suffered and survived the extremes of nature as well as the failure of social systems.

Looking for traces of subjectivity and agency in the 1902 images, we were drawn back to the photograph of rural folk traveling with a team of oxen and their cooking and shelter accoutrements, prepared to continue life in another location. Life also continues in the pose of several women pictured in figure 7, a stereograph of refugees in Fort-de-France. To the left of center in the foreground, one woman holds aloft a naked, lighter-skinned infant who appears to be teething or perhaps chewing vigorously on something (paper? food? sugarcane?) and presents the baby to viewers as if challenging them/us to share responsibility for its fate. Elsewhere in the frame, four or more of the viewers stare directly back at the camera, thereby resisting their depiction as passive, victimized objects. Instead, their posture and concern with a variety of objects, along with the ocular intensity, project a strong sense of what film critic Anna Everett terms “returning the gaze.”16

Figure 7. Street in Fort de France and refugees from Mont Pelé’s terrible eruption, by Underwood and Underwood, 1902. Courtesy of Keystone-Mast Collection; University of California, Riverside; California Museum of Photography.

Like Zephirin and Ferdinand in Haiti and New Orleans, these Martinicans embody grace under pressure and a will to survive even when cracks in the social apparatus needlessly intensify human vulnerability to natural calamities.

Kevin Meehan is a professor of English at the University of Central Florida. His research focuses on comparative Caribbean and African American literature and culture and climate change education. His current project is a translation of selected prose by Léon-Gontran Damas. Paulette Richards is a lecturer at the Georgia Institute of Technology. She has published on Terry McMillan and on imperial fashion in film adaptations of Jane Austen novels, and will be a Fulbright Scholar in Senegal during 2013–14.

1 Aimé Césaire, Cahier d’un retour au pays natal, in Aimé Césaire: The Collected Poetry, trans. Clayton Eshleman and Annette Smith (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 34–35.

2 “Action Taken by the House,” New York Times, 13 May 1902, A-1.

3 Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Picador, 2007), 355.

4 Ibid., 518–25.

5 For an example, see James E. Taylor’s drawing of people lined up at the Freedman’s Bureau office in Richmond, Virginia, in 1866, gdb.voanews.com/E215422F-C1F5-43C7-9112-B22806F05199_w640_r1_s.jpg.

6 See Carlos Antonio Rios’s photo of the Houston FEMA office, www2.ljworld.com/photos/galleries/hurricane_katrina/5834/.

7 Many images from this distribution site are captured in a photo montage published by the Los Angeles Times, www.latimes.com/la-fg-haiti-hires-html,0,5775052.htmlstory.

8 Patrick Bellegarde-Smith, “A Man-Made Disaster: The Earthquake of January 12, 2010—A Haitian Perspective,” Journal of Black Studies 42, no. 2 (2011): 265.

9 See Tom Gill, Tropical Forests of the Caribbean (Washington DC: Tropical Plant Research Foundation and Charles Lathrop Pack Forestry Foundation, 1931), 137–46.

10 See Marie Chauvet, Love, Anger, Madness: A Haitian Trilogy, trans. Rose-Myriam Rejuis and Val Vinokur, with introduction by Edwidge Danticat (New York: Modern Library, 2009), 45–47; originally published as Amour, colère, et folie (Paris: Gallimard, 1968); and Ernst Prophète, Trafic de Compêche (c. 1980, oil on masonite, 16 ¼ x 30 in), reproduced in Jonathan Demme and Kirsten Coyne, eds., Haiti: Three Visions: Etienne Chavannes, Edgar Jean-Baptiste, Ernst Prophète (New York: Kaliko, 1994), 66, fig. 37.

11 See Maria Mies, The Village and the World: My Life, Our Times (North Melbourne, Australia: Spinifax, 2010), 192–93; and Jonathan M. Katz, The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster (New York: Palgrave, 2013).

12 See Robert Corbett, “The Result of the Petion/Boyer Years: Subsistence Farming,” www.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/boyeresult.htm%20 (accessed 9 August 2012); Carolyn Fick, The Making of Haiti: The San Domingo Revolution from Below (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1990), 180; Kevin Meehan, People Get Ready: African American and Caribbean Cultural Exchange (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009), 82–83, 190n10; and Mimi Sheller, Democracy after Slavery: Black Publics and Peasant Radicalism in Haiti and Jamaica (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), 46–52.

13 Mats Lundahl, Poverty in Haiti: Essays on Underdevelopment and Postdisaster Prospects (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), xiii.

14 For Amenold Pierre’s remarks at the National Science Foundation on direct and indirect earthquake impacts in rural Haiti, see www.youtube.com/watch?v=nY-1wrZcSkM.

15 Zephirin’s painting may be seen at media.smithsonianmag.com/images/Haiti-Under-the-Rubble-Frantz-Zephirin-11.jpg. The longer article featured more images; see www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/In-Haiti-the-Art-of-Resiliance.html.

16 Anna Everett, Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black film Criticism, 1909–1940 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), 8.