The Fragile Joy of Staying – If Only in Song: On Bad Bunny’s Residency

My seat neighbors, two best friends clinging to each other, voices breaking and tears streaming as they chanted every lyric of ‘Debí Tirar Más Fotos” (I Should Have Taken More Photos): their friendship louder than the song itself. Photo by the author. All rights reserved.

by Wilfredo José Burgos Matos

For weeks, millions worldwide queued online and in marathon lines for the event of the century: Bad Bunny’s residency at the Coliseo de Puerto Rico. Conceptually, this massive showcase placed Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricanness squarely at the center of global attention, reaffirming national identity and belonging. Simultaneously, it operated as an economic intervention, infusing the island with an influx of tourism, hotel and travel packages, and consumption that has transformed the concert into a temporary but significant driver of cultural and financial capital for locals.

Seeing the global impact it is having and knowing I might never be able to experience something like it again, I attended the tenth concert on Friday, August 1. On the day, I stepped into a sweltering golden San Juan afternoon where the heat clung to the skin and slowed the air. Inside, what unfolded was more than a concert. It was, as many called it, “an experience”: a reckoning with Puerto Rican memory, heartbreak, diaspora mourning, and the pursuit of joy amid gentrification, displacement, and the enduring weight of U.S. colonialism. Bad Bunny’s production traced the pulse of Puerto Rican popular music across time, weaving together tropes that revealed the textures of race, gender, and class identities, until the show itself breathed as a living archive.

The night opened with percussionist Julito Gastón leading an Afro–Puerto Rican batey de bomba, the communal space where rhythm, dance, and performance converge in Puerto Rican’s oldest musical form. Suddenly, reggaetón crashed into the barriles (bomba drums)in “ALAMBRE PúA” (Barbed Wire). Bad Bunny’s entrance alongside the drums staged a sonic dialogue between bomba and reggaetón, highlighting their intertwined histories.

As Petra Rivera-Rideau argues, reggaetón is rooted in Afro-diasporic traditions, though its Black origins are often obscured to appeal to white and middle-class sensibilities. Bad Bunny’s own racial positioning has sparked debate. Some call him jabao – a Caribbean term referring to light-skinned individuals with discernible African ancestry traits – while others stress his non-Blackness. The opening acknowledged this racial ambiguity. Rather than appropriating Afro–Puerto Rican expression, he staged an encounter, foregrounding entangled genealogies of sound and presenting them as complementary, not oppositional.

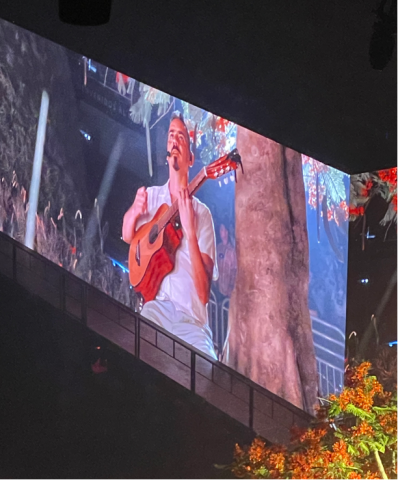

Sonic geographies are central to the residency. From the outset, the concert resisted reducing Puerto Rican Blackness to coastal imaginaries. Still with the barriles resounding, songs like “KETU TeCRÉ,” “EL CLúB,” “LA SANTA,” and “PIToRRO DE COCO” unfolded on a hilltop stage adorned with flamboyanes, plantain trees, a highway billboard, and a Puerto Rican cuatro player, his strings unfurling defiantly into the night. The cuatro, Puerto Rico’s national instrument, is distinguished by its ten paired steel strings and violin-like shape, which produces a bright sonority, historically central to music from the countryside and rural cultural expression.

Sonic geographies are central to the residency. From the outset, the concert resisted reducing Puerto Rican Blackness to coastal imaginaries

This setting repositioned Afro–Puerto Rican cultural life within the island’s interior, unsettling dominant geographies of negritud. The billboard, intruding on the natural landscape, symbolized land exploitation and capitalist encroachment. By blending the cuatro’s timbre with Black aesthetics, Bad Bunny unsettled the notion of música típica as the island’s most “authentic,” non-Black expression, transforming the stage itself into a site of contestation.

After the rave-like eruption of “El Apagón,” the mood softened. Under a tree with only a guitarist, Bad Bunny sang “VETE” and “TURiSTA.” The sudden quiet peeled away spectacle, evoking intimacy and loss. Reggaetón, often dismissed as pleasure-only, revealed its veins of melancholy and vulnerability.

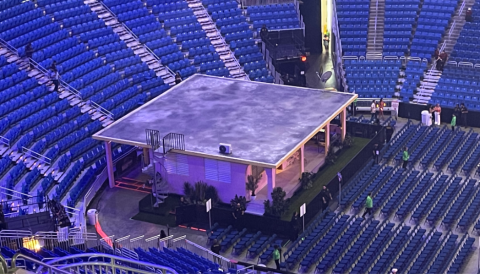

Bad Bunny spotlighted working- and middle-class urban experiences often erased from glossy island imaginaries. The marquesina became a vital socio-cultural space: a vessel of youth, memory, and diasporic mourning.

The focus then shifted to the now-iconic casita, a secondary stage evoking the party de marquesina (Puerto Rican open air garage parties). Here, perreo nostalgia surged with “Safaera” and “EoO.” By conjuring this rite of passage from adolescence to adulthood, Bad Bunny spotlighted working- and middle-class urban experiences often erased from glossy island imaginaries. The marquesina became a vital socio-cultural space: a vessel of youth, memory, and diasporic mourning. For those abroad, it was a sudden return home. For those on the island, a fragile yet enduring ritual of social life.

Every night, new internationally renowned artists attend the party at the casita. Some of the stars include Ivy Queen, Penélope Cruz, Zuleyka Rivera, Benicio del Toro, and Jon Hamm. On this particular evening, the night’s special guest was Arcángel, who stormed in with “Me Acostumbré,” pulling the show into Latin trap and underscoring Bad Bunny’s versatility and origins. Then Los Pleneros de la Cresta burst into the casita, flooding it with plena, often called the island’s sung newspaper, a popular tradition of working-class expression where social critique, gossip, resistance, and joy circulate through rhythm and verse.

Back on the main stage, “LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAii” (What Came to Pass in Hawai’i) mourned an island scarred by colonialism, militarization, and exploitation. The resonance with Puerto Rico was undeniable: two archipelagos commodified, their people sidelined, their sovereignty stolen. Hawai’i’s forced statehood in 1959 resonates directly with Puerto Rico’s unresolved status; two nations bound by shared wounds and the fight for self-determination.

Then came salsa. El Búho Loco, one of the island’s beloved salsa radio voices, narrated the genre’s history before ushering in Los Sobrinos, a young orchestra carrying salsa forward. Their set – “ CALLAÍTA,” “BAILE INoLVIDABLE,” “DtMF (DEBÍ tIRAR MÁS FOTOS),” “LA MuDANZA”– affirmed memory and belonging. During “LA MuDANZA,” the demand that only Puerto Ricans shout “¡Yo soy de P FKN R! (I am from P FKN R)” crystallized the central tension: how to go global without losing the local specificity of Puerto Rican sensibilities.

Over three hours, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio delivered a meticulously orchestrated performance that swung between celebratory, defiant, and intimate, always centering the communal. Every beat and image built a sonic and spatial narrative that, while rooted in Puerto Rican experience, resonated worldwide. His curatorial choices underscored his iconhood, his refusal to abandon Puerto Rico, and his call to shield the island from exploitative foreign interests.

Through every genre pivot and spatial cue, Bad Bunny staged a refusal, a reminder that Puerto Rico is not for sale. Even within the contradictions of capitalist spectacle, the desire for sovereignty pulsed through. For three hours, I too believed I would never leave Puerto Rico. I danced, I remembered, I wept. But when the lights came up, I carried with me the aftertaste of diaspora: the endless motion, the grief of always departing, and the fragile joy of staying — if only in song.

Bad Bunny’s residency runs from July 11 through September 14, 2025, spanning 30 concerts. He will then embark on his “Debí Tirar Más Fotos” World Tour, which is set to kick off on November 21, 2025, in Santo Domingo and run through July 22, 2026, spanning Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America.

Wilfredo José Burgos Matos, Ph.D., is a writer, academic, and performance artist. His book project tentatively titled “Amargue: The Communal Ecologies of a Dominican Feeling,” examines the affective, cultural, and sociohistorical dimensions of Dominican and Dominican-American communal life through the lens of sonic affect and emotional expression. He has published and presented his work in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Spain, Cuba, Haiti, and the United States. He specializes in Caribbean sounds, music, and affective geographies. Learn more about him at wilfredojose.com.