'Copresence' Before the Archive

Tyler Grand Pre

'Copresence' Before the Archive

Tyler Grand Pre

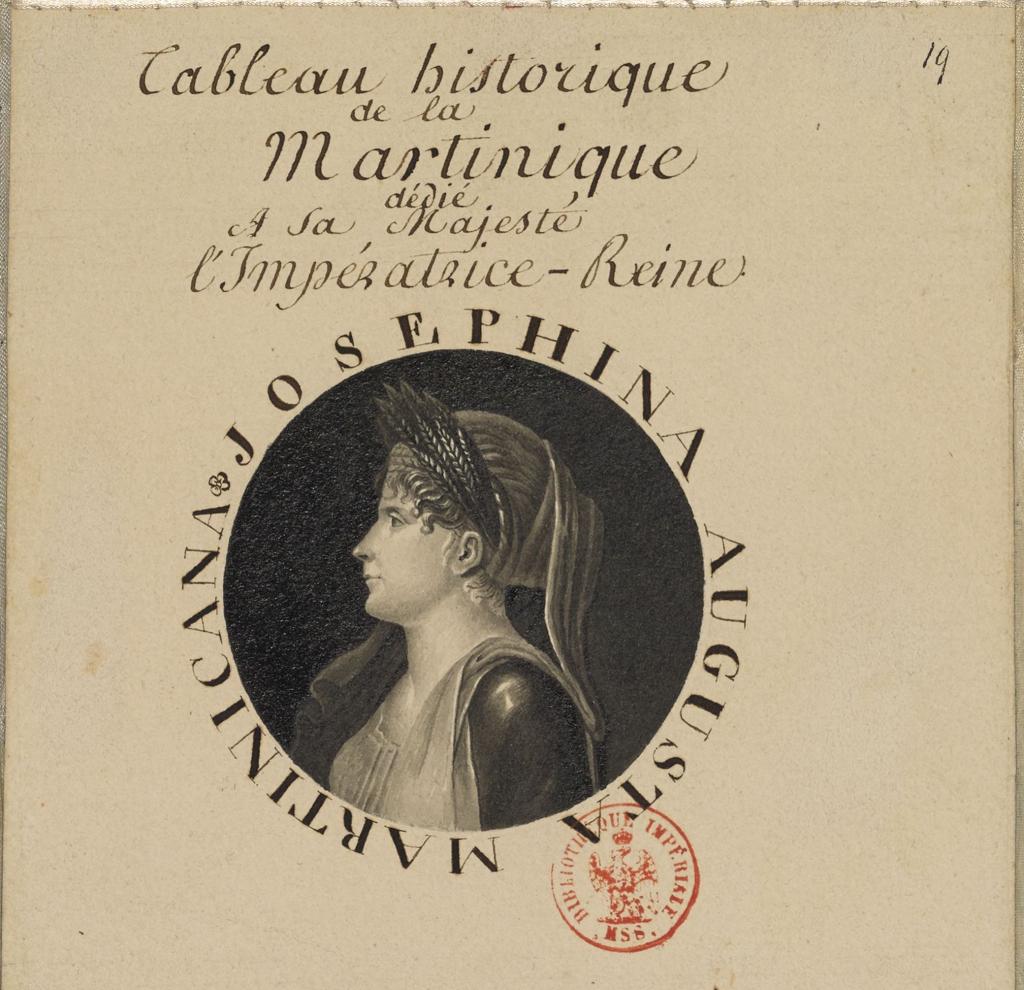

Detail from “Tableau historique de la Martinique: composé pour l'Impératrice Joséphine par l’abbé Nicolas Halma.” 1805-1809. Bibliothèque nationale de France

“Encore une objection ! une seule, mais de grâce une seule : je n'ai pas le droit de calculer la vie à mon empan fuligineux ; de me réduire à ce petit rien ellipsoïdal qui tremble à quatre doigts au-dessus de la ligne, moi homme, d'ainsi bouleverser la création, que je me comprenne entre latitude et longitude !”

– Aimé Césaire, Cahier d’un retour au pays natal

While examining Césaire’s poetic shifts in pronouns and subject positions in my recently published article “Inflecting the French” – from a pronounless search for meaning outside of colonial discourse, to a tenuous “we” of shared ancestry and personal memory, to an intersubjective melting in the indefinite pronoun “on” – I was struck by the way this poetics of intersubjectivity relies on a subtle cartographic conceit openly addressed in the epigraph above: “One more thing! Only one, but please make it only one: I have no right to measure life by my sooty finger span; to reduce myself this little ellipsoidal nothing that trembles four fingers above the line, I a man, to so overturn creation that I include myself between latitude and longitude”(Notebook 14). By approaching Martinique (the people and the island) as the thingified assemblage of “this ellipsoidal nothing” – describing the island's appearance on a world map – the poetic speaker’s objection to being measured within the colonial metrics of a figural map parallels his poetic refusal to transcend his colonial reality through the universal pretenses of the lyric “I.” As I argue in my essay, Césaire instead discursively remaps the Antilles through the speaker’s deconstructive approach to his native land in an “I/it” as opposed to “I/you” relationship. And so, not unlike the “unruly contours” that make “things fidget” on Kei Miller’s island in “What the Mapmaker Ought to Know,” Césaire’s poetics of intersubjectivity cause the island to tremble on the map and tongue in ways that my brief summary here can only preview (Miller 15).

However, I would like to briefly engage some of the archival work I did while preparing to present on the essay at the 2021 Graduate edition of the Brown University Political Concepts Conference. With Césaire’s objection as my model, I searched the digital collections at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF) as well as the archives at the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) at first trying to imagine what maps or atlases he might have encountered before writing what would become the first version of the Cahier published in 1939 (Césaire, Poésie, 37). But gradually I found myself not searching so much for a particular document as much as a kind of document that speaks to that symbolic refusal to be reduced to colonial representation.

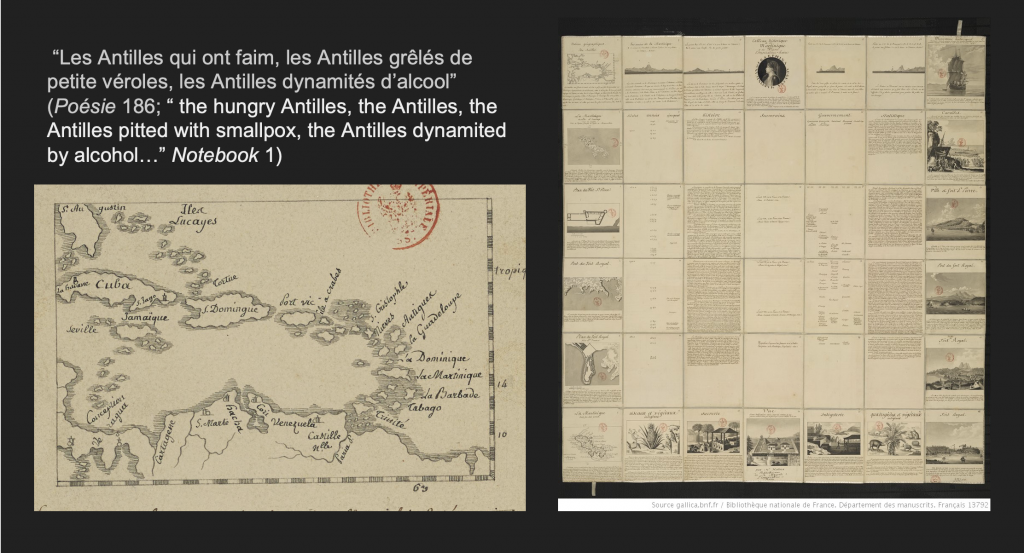

Detail from “Tableau historique de la Martinique: composé pour l'Impératrice Joséphine par l’abbé Nicolas Halma.” 1805-1809. Bibliothèque Nationale de France

What I found was a “Tableau historique de la Martinique” made specifically for Empress Joséphine by l’abbé Nicolas Halma, the librarian at Malmaison charged with educating the empress in history and geography. It was produced as a part of a series of “tableaux historiques et chronologiques” containing historical accounts of French territories and reproductions of maps and illustrations from a variety of famous works available at the time. What stood out to me at first was the way this tableau almost perfectly captures the sweeping, particularizing movement in the opening lines of Césaire’s poem from “the hungry Antilles, the Antilles, the Antilles pitted with smallpox, the Antilles dynamited by alcohol...” (Césaire, Notebook, 1),

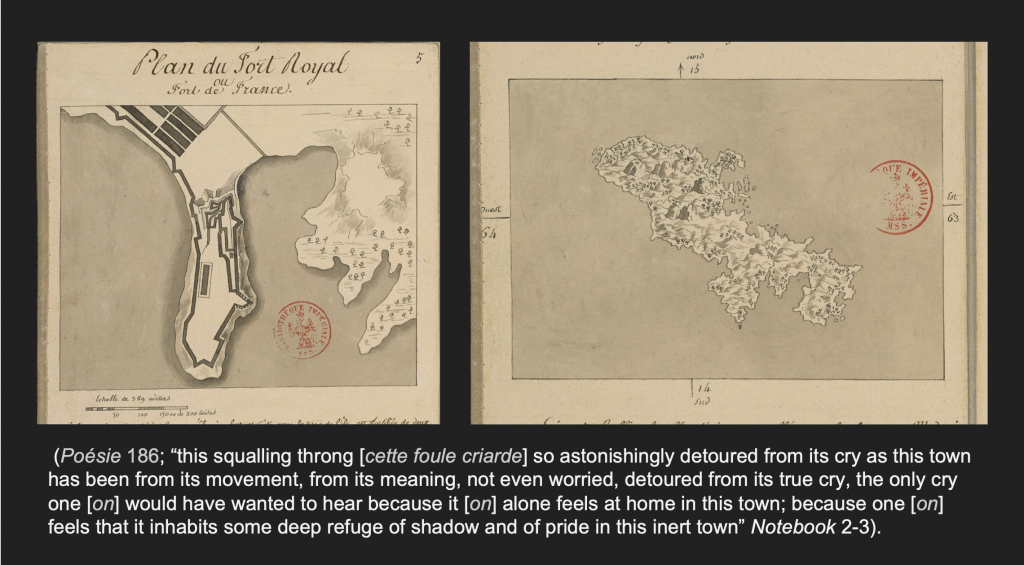

Screenshot from the presentation “Elliptical Ontology: The Geometry of Blood and the Grammar of Dispossession,” presented at the 2021 Political Concepts: Graduate Student Edition conference, which was published on Youtube by the conference organizers

to “this town sprawled-flat, toppled,” to “this squalling throng so astonishingly detoured from its cry as this town has been from its movement, from its meaning, not even worried, detoured from its true cry, the only cry one [on] would have wanted to hear because it [on] alone feels at home in this town; because one [on] feels that it inhabits some deep refuge of shadow and of pride in this town” (Poésie 186; Notebook 2-3).

Screenshot from the presentation “Elliptical Ontology: The Geometry of Blood and the Grammar of Dispossession,” presented at the 2021 Political Concepts: Graduate Student Edition conference, which was published on Youtube by the conference organizers

I insert some of the French in the last quote to highlight the way Césaire inflects the lyric tradition with the intersubjective valences of negritude through a poetic use of the indefinite pronoun "on" (which can, depending on the context and intention of the speaker, speak to any of the other personal pronouns). As I note in a section of the essay entitled “The Fugitive Grammar of Intersubjectivity,” “Because Martinique as it exists on a map is conflated with the affective representations of the black community as it exists in Enlightenment discourse, the use of on [...] affords the speaker a kind of grammatical camouflage in his movement about the geo-discursive spaces of the island and traversal of the [...] cartographically framed divide between him and ‘cette ville’” (Grand Pre 413).

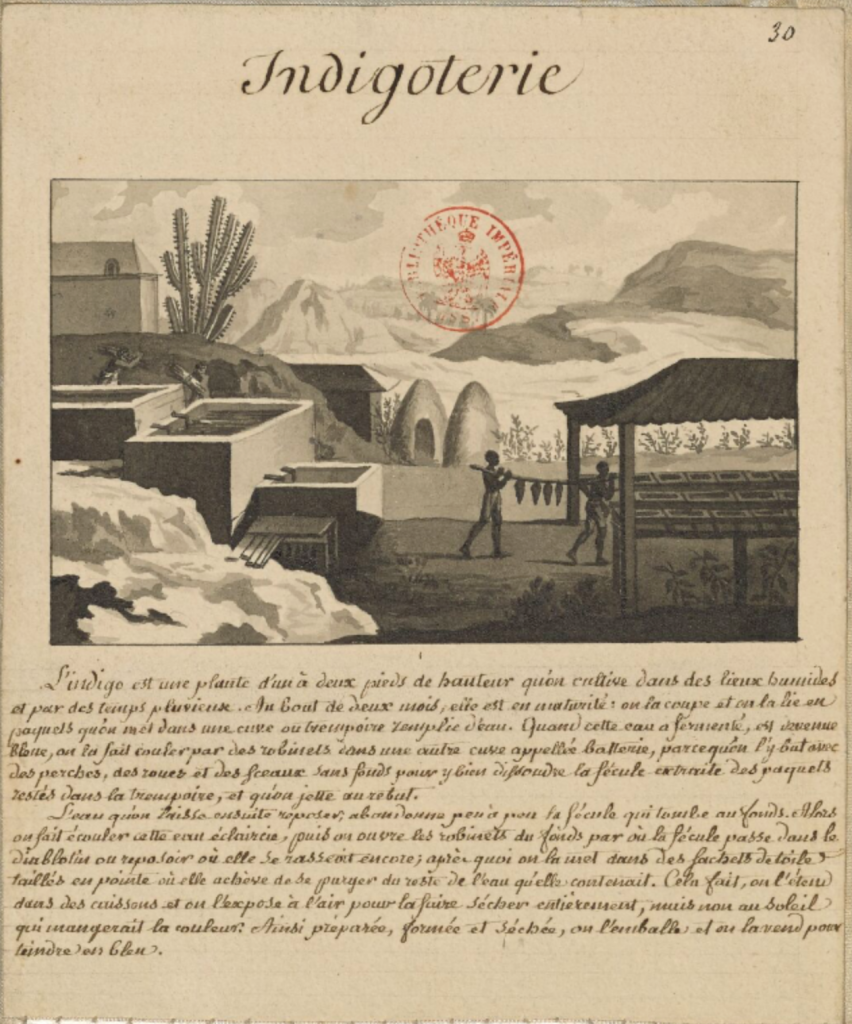

Going beyond the scope of my published essay and presentation – for which these maps started off as just an illustration – I noticed the way the indefinite pronoun "on" functions in the Tableau’s description of “Indigoterie” (the site and tools of Indigo processing) as a subjective meeting place for the overseer’s disciplining eye/ hand and the enslaved bodies doing the labor. Both that grammatical bridge across that cartesian divide and its visual representation tremble a lot like the grammar of Césaire’s map when one considers a part of the original text to “Indigoterie” in Jean Baptiste du Tertre’s Histoire générale des Antilles (1667-71) omitted by l’abbé Halma. In particular, Halma leaves out the section where Du Tertre asserts the importance of making the cisterns in which the most chemically hazardous part of the Indigo processing is conducted out of stone and cement since making it out of wood had resulted in the deaths “des François & des Négres” (of French and Blacks) (Du Tertre, 110).

Detail from “Tableau historique de la Martinique: composé pour l'Impératrice Joséphine par l’abbé Nicolas Halma.” 1805-1809. Bibliothèque nationale de France

The plantocratic fantasy of harmonious relations of slavery under constant surveillance – signified as the pronoun “on” and visualized through the vantage point of this illustration as well as the inclusion of an overseer in the original – is at odds with the reality that most certainly led planters to abandon their enslaved to the noxious fumes of the indigo plantation built with improper materials to maximize profit. Not only is it that black overseers were used to maintain discipline and order, but these reflections invite us to read into where there were unsurveilled locations for black resistance, creativity, and life within the necropolitics of the plantation. Thus “on” not only signals an unsettled cartesian divide between the “[les] François & [les] Nègres,” but it provides an ethical site of counter-historical reading – a site that registers with Saidiya Hartman’s impulse to read beyond “the surface of discourse” that buries racialized subjects within the archive of their “encounter with Power” (Hartman 2).

Reading with Césaire, or Hartman for that matter, I experienced a kind of ‘copresence,’ to adapt the concept of one of my fellow presenters at the Brown conference – and this copresence before the archive stuck with me while doing some archival work in Martinique this past winter break. Standing on the edge of La Savane facing what is left of the statue of l’Impératrice Joséphine – the privileged subject of the Tableau – I found myself thinking of Césaire’s symbolic map, its representational excesses, and recited under my breath his address to “those who never invented anything.”

As an older Martinican man reminded me while chatting about the history of the cracked, graffiti-ridden marble, this statue had trembled for years with the legacy of the plantation and the socio-political hierarchies of an island whose industry is still run by the békés (the descendants of the slaver planter class). Erected in 1859 as a part of the Second Empire’s wave of Bonapartist monuments, the statue towered as a symbol of the Old Martinique over the so-called nouveaux libres forced to work on the old plantations by post-emancipation vagrancy laws (Brown 43). Considering the way the statue looked towards the plantation of La Pagerie in Les Trois Îlets, it is not surprising Joséphine’s likeness continued to evoke the story that she had convinced Napoleon to reinstitute slavery in the French colonies in 1802.

From the throwing of red paint to the beheading of Joséphine’s statue in the 1990s, such a legacy invited repeated vandalism that finally led to the statue being torn down completely in the summer of 2020. This was another kind of copresence that took place amidst the global response to George Floyd’s murder as well as the controversy around Macron’s decree that no monuments would be removed in French territories – racist or not. Like the Duke of Orleans’ statue removed by the French at the moment of Algerian independence, all that remains of Josephine is an empty pedestal. Whatever may be the next mark or gesture for this palimpsest of protest, for the moment, it trembles as a monument to popular memory.

Photo of the statue of L’impératrice Joséphine, Credit. Photo by Tyler Grand Pre, 2023. Copyright Tyler Grand Pre. All Rights Reserved

References

Brown, Laurence. “Créole Bonapartism and Post-Emancipation Society : Martinique's Monument to the Empress Joséphine.” Outre-mers 93, no. 350 (2006): 39–49. https://doi.org/10.3406/outre.2006.4188.

Césaire, Aimé. Notebook of a Return to the Native Land. Translated and edited by Clayton Eshleman and Annette Smith. Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

—. Poésie, théâtre, essais et discours. Edited by A. James Arnold. Paris: CNRS : Présence Africaine, c2013.

Du Tertre, Jean Baptiste. Histoire generale des Antilles habitée par les François. Paris: T. Iolly, 1667-71.

Edwards, Brent Hayes. “The Taste of the Archive.” Callaloo 35, no. 4 (2012): 944–72. https://doi.org/10.1353/cal.2013.0002.

“Elliptical Ontology: The Geometry of Blood and the Grammar of Dispossession,” presented at the 2021 Political Concepts: Graduate Student Edition conference.

Frempong, Deborah. “Copresence.” “Political Concepts: Graduate Student” Edition (2021). https://sites.brown.edu/political-concepts-spring21/speakers/deborah-fr…

Halma, Nicolas B. “Tableau historique de la Martinique: composé pour l'Impératrice Joséphine par l’abbé Nicolas Halma.” 1805-1809. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des manuscrits, ark:/12148/btv1b52507384.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (2008): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1.

Miller, Kei. The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion. Carcanet, 2014.

Vial, Charles-Éloi. « Joséphine et les leçons d’histoire de Malmaison », Revue de la BNF, vol. 53, no. 2, 2016, pp. 173-184.