sx art 7

-Marinna Shareef

GODS

From my first glimpses of her video and painted works, Marinna Shareef's practice stood out. In a sea of contemporary Caribbean arts awash with solemnity and seriousness on one hand, and pointed celebrations of resilience on the other, I was drawn into the wild and layered playfulness of her creative world. One can see the influences of artists like Wendy Nanan in her work but her bright, bold colors and use of recognizable icons register a Trinidad that is both familiar and which is often undocumented in Caribbean visual practice. Most impressive is Shareef's vulnerability; she invites her audience close-up, provoking interrogation of ourselves through her reflections about her challenges with living with bipolar disorder. I finally met Marinna this September, after selecting her as the 2025-2026 Artist-in-Residence at the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change, at York University, and in the process of working with her, of observing her practice close-up, have only become more excited to see how her future unfolds. Below, she shares some thoughts about her journey so far.-Andil Gosine

The official diagnosis came when I became an adult, but I have dealt with bipolar disorder my entire life. I remember feeling emotions in a way that others could not relate to early on. Teachers would get frustrated with me in school, and I myself could not understand why I would often feel so distraught. In the first year of my Fine Arts degree at the University of the West Indies (St Augustine), I would go into weeks of depression while not being able to go to school or take care of myself. I would also have days where I created multiple artworks at a time and would not sleep due to the rush of energy I had. After diagnosis of bipolar disorder at the age of eighteen, I found helpful medication. My art practice reflected this journey. I make work about my bipolar disorder in order to understand my relationship with it. Simultaneously, my conversation with my mental health is transforming as I continue to create.

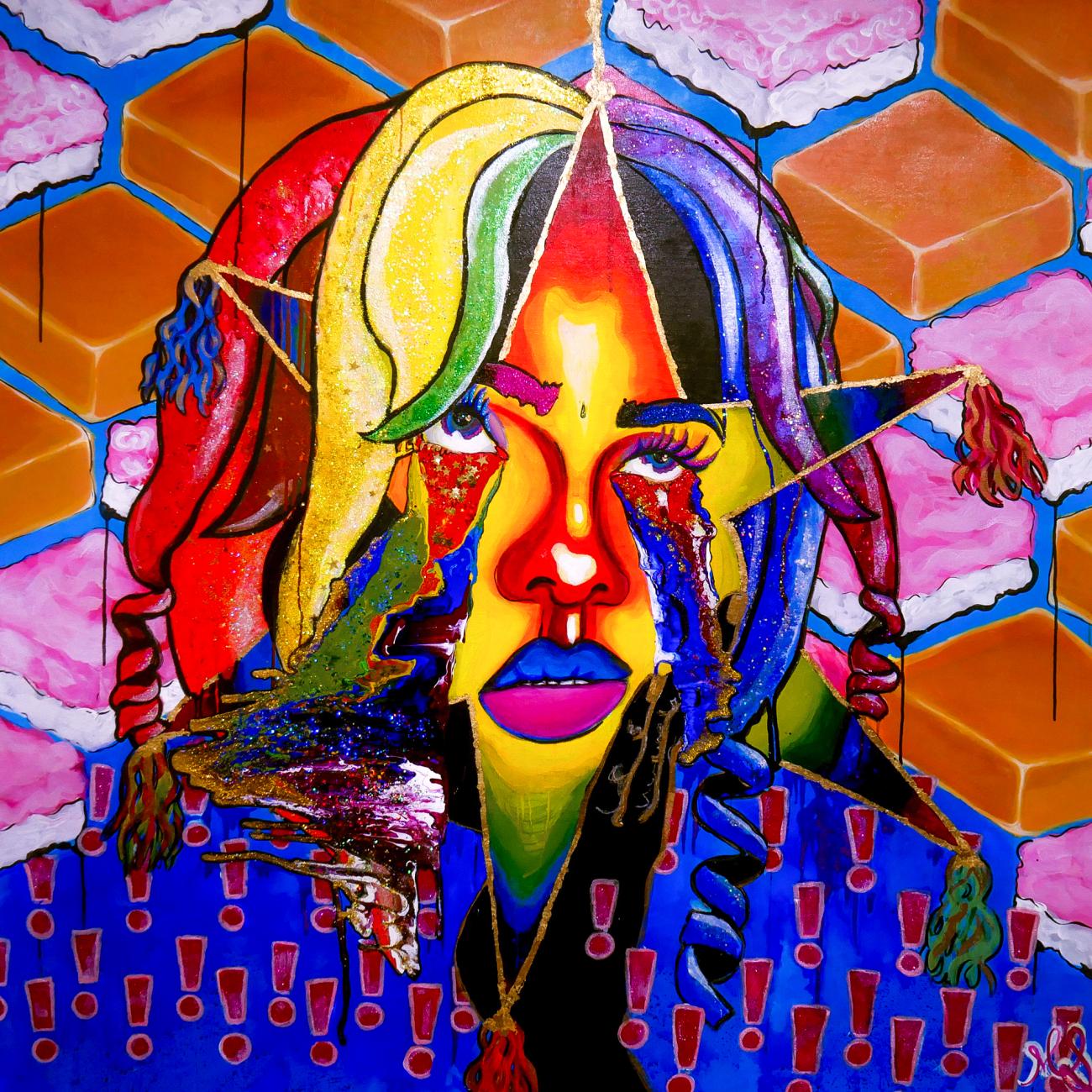

Creating my artworks begins with the translation of my emotions into metaphors. To process my experience with bipolar disorder, I imagine my feelings as a kind of god, powerful yet flawed beings. The gods take over my mind. My art builds a mythology around these characters, with the God of Depression and the God of Mania as central figures. Each inhabits their own world. The depressive god exists in a blue-tinged, slow-moving realm filled with sunken mattresses and endless pillows. They are caught in a kind of heavy, immobilized, spell. I often use bed motifs to depict the all-consuming, swallowing sensation of depression. In contrast, the manic god lives in a world that resembles a never-ending birthday party, over-saturated with color, excessive sweetness, and overwhelming joy. It’s bright, almost painfully so.

My gods of Mania and Depression are not distant mythological beings imported from somewhere else. They are intimate, and shaped by my landscape, my culture, and my memory. Mania doesn’t come in looking like a textbook symptom, it shows up in a rush of colors and sugar, with kiss cake and barfi to boot. Depression isn’t some abstract void, it’s surrounded by the bed I live in.

Mania can make you feel like you are on top of the world. I started using local snacks to metaphorically describe the sweetness and eventual crash of mania. It reminded me of childhood in Santa Cruz, buying “Bigfoot” and “Kiss” cakes at the school parlor, running around with a sugar high. My Aunt would bring me packs of iced gems from town, and those memories became linked to that kind of excessive, fleeting joy. Mania, for me, feels like being trapped in a candyland. Everything is too bright, too sweet, too much. It may look delightful, but it’s harmful underneath.

Most recently, I collaborated with Andil Gosine to create a God of Whimsy painting. I started as I would with my other projects, by reading about him through his book Nature’s Wild. I picked out visual references from the text and used things that stood out like his checkered shirt and his love for Miss Piggy, and his love for macarons. From our back-and-forth collaboration emerged a god that would describe the outward lightheartedness of his personality, but which also hinted at more serious matters. Andil wanted the hues of the piece to deliberately cite trans pride colors at a time of renewed attack on queer communities, especially trans people.

God of Whimsy by Marinna Shareef with Andil Gosine, 2025,

Mixed Media on board, 16” x 16”Sweet Nostalgia?, 2024, Mixed Media on board, 16” x 16”

Dolls also feature in my work. Growing up in the 2000s, I was obsessed with Barbie and Bratz. My ‘girlhood’ was very pink, filled with computer games and dolls that embodied confidence and individuality. Even now, I’m drawn to them. I think it’s because those dolls represented an ideal I didn’t often feel, a self-assured, glamorous version of myself. I channel and perform this idealized imagination of them. When I combine these elements with cultural references like bindis or religious iconography, my portraits start to resemble murtis (sculptures of Hindu gods). That resemblance isn’t accidental, but it’s not entirely intentional either. It just happens through the intersection of personal myth-making, femininity, and South Asian visual culture. The dolls and candies connect my work to my childhood. Using parallels of toys or games I enjoyed as a kid along with traumatic situations I have experienced, I reframe how I feel about these memories.

God of Mania Portrait, 2023, Digital Image

The Manic God, 2019, Digital Image

I have also become more interested in video experimentation. In 2022, during a residency with The Caribbean Digital and Alice Yard, I was able to devote six months to digital media. That time allowed me to shift from focusing solely on bipolar disorder to also exploring trauma, specifically how it cycles through Indo-Caribbean families. I didn’t want to make work that re-traumatized me, but I did want to tell the story in a way that felt therapeutic. In Consequences of Remembering, I explored leaving home while my grandmother was ill. It was a painful time, but the video focuses on growth instead of grief. It was shown in my 2024 digital exhibition the things I cannot say, with the video projected onto a concrete grave by North Eleven, rooting the work in a physical, Trinidadian context.

People tell me I’m brave for making work about bipolar disorder and trauma. I don’t know if I’d call it brave. It’s hard, yes. But when you live with something every day, when you're constantly misunderstood or dismissed, it becomes all-consuming. Making art about anything else didn’t make sense. I had to understand myself first. Of course, there’s pushback. I’ve had my work dismissed as “devil ting.” People often label what they don’t understand as evil. I’ve been told I’m being negative, but I disagree. My work is like a visual journal. Writing about my experience isn’t negativity. It’s honesty.

Marinna would like to thank Christopher Cozier for posing questions which prompted much of this reflection.