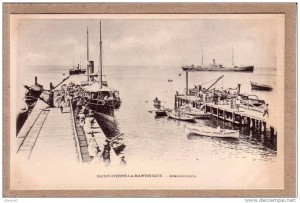

Figure 1. Saint Pierre La Martinique—Appontements, postcard, c. 1900. Courtesy of Lisa Paravisini-Gebert.

A peaceful port. Sailboats sleepily sway in the light wind. A seemingly empty steamer lies in silent pause. Barrels of rum, patiently waiting in aromatic oak barrels. People of all walks of life—stevedores in repose, weary fishermen selling the last of their silvery cargo, children, businessmen, head-tie covered màchannes, housewives looking for fresh produce, ladies under pastel-colored hats making their way to the boat for Fort-de-France—seem relaxed as they walk on the quay, unrushed in the hot afternoon sun. This is what came to mind as I observed the postcard of St. Pierre (fig. 1) before reading Daniel Thaly’s poems about the doomed city, especially his depiction of the harbor in poem 34; I was surprised to discover the same images in the unruffled, elegiac verses he wrote about his beloved port. Thaly’s poems—particularly “Au Large du Mont Pelé (À St. Pierre),” “In Memoriam,” “Saint-Pierre,” and “À la Fontaine Chaude,” all convey the same languor that struck me in the series of sepia-toned “before and after” photos of a city—once considered to be the wickedest in the West Indies (lively to the point where St. Pierre’s bishop left in a huff, condemning it for its degeneration and corruption)—and the destruction it suffered with the violent eruption of Mont Pelée. Daniel Thaly (1878–1950) was one of the few poets to have dealt with the anguish left in the eruption’s aftermath.1 Jack Corzani stresses what appears to be a dearth of literature recounting the horror of the Mont Pelée cataclysm, saying that after the disaster, most writers would not or could not take on the task of speaking about the unspeakable, preferring to dwell either on the demonization of St. Pierre itself (divorced from the fateful event) as a center for debauchery, a “Sodom and Gomorrah,” or the extolling of its virtues as a lost Paradise.2 Thaly, however, faces the trauma directly.

On 8 May 1902—Ascension Day—pyroclastic flows ravaged the port city of St. Pierre. Once called the Paris of the Antilles, this attractive and bustling city became an empty, ghostly ruin. The nuée ardente (a term coined by geologist Alfred Lacroix)—the burning, glowing cloud of gases and ash that destroyed the city— managed to, as Dominican historian Lennox Honychurch describes it, “skim across water and destroy even the ships at anchor in the bay.” Doctor and poet Daniel Thaly was one of the concerned Dominicans who visited St. Pierre a month after the eruption, traveling in the steamer The Yare on an excursion organized by Dominica’s governor Hesketh Bell: “Everybody who was anybody in Roseau society was aboard: Dr. Nicholls [Phyllis Allfrey’s grandfather], Dr. Rees-Williams [Jean Rhys’ father], Dr. Thaly, Sterns Fadelle [a local historian], Judge Pemberton, members of the Legislative Council and Town Board. They arrived upon a scene of ruin and desolation; the bodies of the dead were still strewn around and smelling to high heaven.”3 It was a visit that would mark not only Thaly’s poetry but Jean Rhys’s work as well, as Elaine Savory argues in her reading of Rhys’s “Heat.”4

Thaly was deeply marked by the St Pierre tragedy as he had lost relatives, former classmates, teachers, and friends in the catastrophic events. Born in Dominica on 2 December 1879, Thaly had attended the St. Pierre Lycée in Martinique (his mother was of Martinican origin) and later studied medicine in Toulouse, France. A doctor practicing in Dominica, Thaly was immersed in art and literature: he was curator of the Victoria Museum in Roseau and worked as an archivist for the Schoelcher Library in Fort-de-France, Martinique.5 As a writer, he was prolific, publishing nine volumes of poetry and contributing to publications such as La Nouvelle Revue Française, Mercure de France, La Phalange, Le Divan, and Canada-West Indies Magazine, among others. Acclaimed as the “Prince of Antillean Poets” in the early twentieth century, and later disparaged as a poète doudouïste that romanticized the colonial ties between France and the Outremer territories, he is considered by some to have been one of the precursors of the Negritude movement; his works are often studied along with those of Aimé Césaire. In “Daniel Thaly: Poet of St. Pierre,” Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert underlines that in spite of his now half-forgotten status, he further solidified his renown as a poet in the aftermath of the Mont Pelée tragedy, which he commemorated through verses “whose evocation of the Antillean landscape is etched with the searing pain of the loss.”6 Indeed, in spite of the serene poetic voice present in most of his poems, Thaly’s verses reflect the deep sadness that such a swift and cataclysmic loss can produce.

Despite having lost part of a world he once knew, a space inhabited by loved ones, Thaly’s descriptions of the aftermath of the eruption maintain the voluptuous slowness of St. Pierre as a locus amoenus “before” its defilement by angry, fire-breathing, infernal monster that is also characteristic of Lafcadio Hearn’s work: “the infernal monster, having broken its bridle; flames spewed out of its angry snout” [“le monstre infernal ayant brisé son frein; les flames ont jailli de sa gueule en colère”].7 In Thaly’s poem 33, “À la Fontaine Chaude,” the heat of the various sources of water is only shown as unnatural and monstrous at the very end of the poem. Before the shocking conclusion and only reference to the volcano—“Fontaine! Ta chaleur te venait d’un cratère”—his numerous references to water only reveal a calm sensuousness, despite the occasional oxymoron where warmth and coolness stand in stark contrast. He describes his dear warm fountain, cooing in the ravine; the waves of diamonds; the boiling springs; and the Caribbean Sea with its deserts of emerald green. Even the night, although stealthy (“présente mais invisible”) is peaceful as it “continued its subterranean work in peace.”8 Nothing is rushed. No screams of horror pierce the night. There are no references to the sheer ghastliness of almost thirty thousand people burned alive. It is as if all the people had died in their sleep, quickly and painlessly.

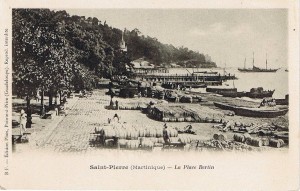

Figure 2. Place Bertin, Port and Lighthouse, postcard, c. 1900. Courtesy of Lisa Paravisini-Gebert.

Figure 2 offers an eerie parallel to poem 33 (dedicated to the warm fountain: “À la Fontaine Chaude”). As elegantly-dressed gentlemen go about their business, stopping to chat, young boys, protected by their wide-brimmed straw hats, walk to their respective stalls or boats to begin a day’s work, and a gendarme stands with his hands in his pockets as he surveys the scene on Place Bertin, the fountain bubbles away on the far right edge of the photo. By the direction of the water sprays and the flags on the idle boats, which floating outward, toward the horizon, one can see that the wind is blowing toward the open sea, away from the mountain. One can almost feel the breeze getting hotter and hotter, the water in the fountain bubbling from the subterranean currents of the volcano, no longer refreshing the passers-by. The biggest warning to the impending disaster—as Thaly suggests in his personification of the fountain (“Fontaine! Ta chaleur te venait d’un cratère”)—stands by unheeded by all. In the daylight, the lighthouse stands as idly as the police officer, and most of the ships, with their bows pointing away from the land, look like they are poised for a rapid escape. But the unsuspecting townspeople go about their daily routine without haste.

In his poem 34 “Saint-Pierre,” Thaly once again focuses on the indolent port (mentioned above in reference to figs. 1 and 2). Everyone is going about their business in total obliviousness of the approaching fiery end: higglers selling coconuts and soursop, the mauby foaming in bottles, doves flying over the sea, dark women in kerchiefs carrying red parasols, sandals lazily scraping along the sidewalks (“des marchandes criaient cocos et corossols”; “le mabi mousse dans les bouteilles”; “des pigeons sur la mer déployaient de beaux vols”; “des câpresses portant de rouges parasols, mettaient . . . le mouchoir à deux pointes”; “sur les trottoirs traînant le bruit des apamols”). In this poem however, the sense of loss is more palpable in his use of the past tense and the repetition of autrefois (once, or once upon a time): “À Saint-Pierre autrefois chantaient mille fontaines” and “À Saint-Pierre autrefois riaient des jeunes femmes” [Once upon a time, in Saint-Pierre, a thousand springs used to sing; Once upon a time, in Saint-Pierre, young women used to laugh]. Here, water—fountains, springs, and the bay—is also prominent. The verses describing the leisure of the sea captains walking along Place Bertin while their colorful three-masted schooners were moored in the harbor and the cheeriness of young ladies dancing the mazourque to the rhythm of the blue waves (eerily described as blades), are cloaked in bitter irony, and the reader is reminded that no one suspected imminent death (“qui ne se doutant pas de leur prochaine mort”).9 One is reminded of Hearn’s seemingly unconcerned question (and answer) in his 1890 “Two Years in the French West Indies”: “Is the great volcano dead? Nobody knows.”10

Figure 3. La Place Bertin, postcard, c. 1900. Courtesy of Lisa Paravisini-Gebert.

In figure 3 we sense the same nonchalance and unhurried movement depicted in the poem—men walking, a sea captain strolling along the promenade, women dancing, waves slapping against the wooden sailboats in cadence, the warm wind blowing. But seen from the point of reference of the “after,” the stillness of rows upon rows of barrels waiting to be loaded (also seen in fig. 2), some covered with tarps (like death shrouds), are reminiscent of the still bodies that would be lined up after the catastrophe (see fig. 4).

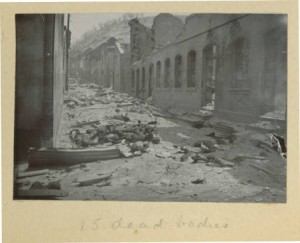

Figure 4. Fifteen Bodies and Rubble, by W. G. Cooper, 1902. Courtesy of the SMU Central Universities Libraries collection.

In Thaly’s “Au Large du Mont Pelé” (also dedicated to St. Pierre), the memory of the natural disaster is relived from the safe distance of the past. While in the aforementioned poems, sea vessels—steamboats and three-masted schooners—float idly and helplessly in the St. Pierre harbor, described as if being observed from Place Bertin, in this one the narrator himself is on board a transatlantic steamer, traveling through Caribbean waters (“traversant les eaux de l’archipel”) on a beautiful and serene night in the tropics, observing Martinique’s dark silhouette and remembering that fateful night from what appears to be a positioning in the remote past. Although the horrors of the eruption seem distant as one of the passengers recounts the story—the old mountain (Mont Pelée) dozes under a gray cloud—the narrator relives the tragedy of the unfortunate city with a sense of immediacy through his connection with the sea. The sea, also personified, as the Place Bertin fountain was in poem 33, looks like it is on fire, reminding the author of the hellish event. Along with the poet, it still cries for St. Pierre, emitting a long tragic sob (“la mer sembla jeter un long sanglot tragique”). The narrator finds solace in the sea, with which he shares a more intimate knowledge of the tragedy and sense of loss, as a fellow witness (“nous deux qui savons tout ce que nous a pris”).11 In his insistence on reducing the first person plural to only two, “nous deux,” the poet/narrator underlines the lonely task of recollecting the past experience and telling it. This intimate and solitary standpoint corroborates Corzani’s comment on the absence of literary voices addressing the traumatic event immediately after. And so there is silence. The “nous deux” of Thaly’s poem maintains the intimacy that only two can share: the narrator and the sea. Looking back at figures 1, 2, and 3, the sea as silent witness is the most salient element that all the photos share. Of course, since St. Pierre is a port town, it would hardly be possible to ignore its presence, but its proximity makes it a witness par excellence. However, the painful absurdity of it all is that many believed that the closeness of water would save them. Unfortunately, the nuée ardente burned everything in its path, including the boats anchored at bay. A month later, when Thaly visited on board The Yare, and years later, during his subsequent visits to Martinique, the sea would always seem to be on fire; the sea would always seem to mourn; and the sea would be more of an omniscient narrator than the poet, as he highlights in “Au Large du Mont Pelé” (Off the Shores of Mont Pelée). The bay of St. Pierre was the sole, true witness.

In his work, the poet has a sense of having lived that historical moment. Thaly was twenty-four years old when the eruption occurred and the immediacy of loss—of loved ones, friends, family, former teachers, as well as the spaces he used to frequent—is apparent in his writing. Other writers that have more directly addressed the Mont Pelée eruption in their work, such as Raphaël Tardon and Aimé Césaire, were not even born then. Their reflections are based on a distant event, filtered through time and further mediated by many different types of discursive and aesthetic sources. In the case of Césaire, the medium used—poetic language—and the shared emotional response to the tragedy of St. Pierre manifestly links him to Thaly through mourning and nostalgia, which echo through their work.12 Césaire’s perspective on the aftermath in Notebook of a Return to the Native Land seems to be turned in two directions. Like Janus, he addresses the past by projecting a prophetic voice into the future, making the event more patent in the reader’s imagination; making it more real by the imminence of its possible recurrence. Or perhaps for Césaire, the disaster never ended:

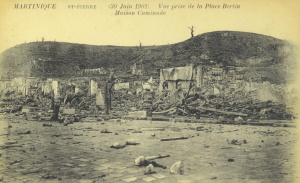

In spite of his closeness to the disaster, Thaly’s verses never connote the absolute finality and impossibility of recovery presented in these lines. The destruction, accumulated debris, desiccated trees, and desolation shown in figure 5 (Place Bertin, Maison Caminade), seems closer to Césaire’s portrayal. Perhaps because he walked through the rubble and wreckage of “this inert town,” to use another repeated trope from Notebook, Thaly found it impossible to speak about what he saw there.At the end of daybreak . . . —the volcanoes will explode, the naked water will bear away the ripe sun stains and nothing will be left but a tepid bubbling pecked at by sea birds—the beach of dreams and the insane awakening.

At the end of daybreak, this town sprawled-flat, toppled from its common sense, inert, winded under its geometric weight of an eternally renewed cross, indocile to its fate, mute, vexed no matter what, incapable of growing with the juice of this earth, self-conscious, clipped, reduced, in breach of fauna and flora.13

Figure 5. Place Bertin, Maison Caminade, by W. G. Cooper, 1902. Courtesy of the SMU Central Universities Libraries collection.

In figures 4 and 5, an unbearable silence is conveyed by the utter barrenness of the scene. In figure 4, the stack of fifteen corpses allows for some degree of recognition: traces of everyday existence; the memory of an inhabited space, transited by human beings, domestic animals, birds, insects; and the murmurs of life. Figure 5, on the other hand, because of the absence of bodies and the charred trees on the desolate hills above, communicates sterility, the “breach of fauna and flora,” and the complete absurdity of the many fragments that are now useless; it is the perfect illustration of a “town sprawled-flat, toppled from its common sense.” Thaly and others who had strong ties to the island tried to make sense of the cataclysm in its aftermath. Honychurch recounts how some of the people that visited from Dominica, a month after the eruption, gathered souvenirs of the devastated city:

Clambering through the debris they searched for mementos of the disaster. Dr. Rees-Williams claimed a pair of large candlesticks that the heat had twisted into an extraordinary shape. [They will become the focus of his daughter’s story “Heat.”] Bell removed a porcelain image of the Virgin Mary from the clutches of a corpse, a statue that “the poor old creature had died clasping to her breast”, he observed. At the end of the day as the Yare sailed back to Dominica it was agreed that “the expedition had been an unforgettable and awe-inspiring experience.”14

Initially, the idea of keeping tokens of a calamity as appalling as this struck me as nonsensical or even boorish. But, as I looked at the photographs of Place Bertin and reread Thaly’s odes to St. Pierre, I understood. By collecting the fragments of the disaster (through writing, photographing, or safeguarding mementos), by gathering the traces of the world as it was before, during, and after the trauma, artists take the first step in the work of reconstruction.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert for providing the materials for this article. All images are postcards in the public domain. Figures 1–3 are postcards circa 1900. Figures 4 and 5 courtesy of the Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library (Latin America and the Caribbean: Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints).

Ivette Romero holds a PhD in French literature from Cornell University and is presently professor of Spanish at Marist College. Her publications include articles on Caribbean literature, women writers, and visual arts. She is coeditor of Women at Sea: Travel Writing and the Margins of Caribbean Discourse (2001), Displacements and Transformations in Caribbean Cultures (2008), and the Repeating Islands blog (with Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert).

1 See Daniel Thaly, Chansons de mer et d’outremer (Paris: La Phalange, 1911), and L’ile et le voyage, petite odyssée d’un poète lointain (Paris: Le Divan, 1923).

2 Jack Corzani, “La Fortune littéraire de la ‘catastrophe de Saint-Pierre,’” in Alain Yacou, ed., Les catastrophes naturelles aux Antilles: D’une Soufrière à une autre (Paris: Éditions Karthala, 1999), 75–97.

3 Lennox Honychurch, “Morne Pele Volcano and Dominica: One Hundred Years since the destruction of St. Pierre,” Public Seismic Network Inc., Dominica (DPSN), dpsninc.org/index.php/stories2/21-morne-pele-volcano-dominica, para. 18 (accessed 8 August 2012).

4 See Elaine Savory, “Memory, Trauma, and Natural Disaster,” in this issue of sx salon, http://smallaxe.net/wordpress3/discussions/2013/05/27/memory-trauma-and-natural-disaster/.

5 “Daniel Thaly,” La Revue Critique, www.larevuecritique.fr/article-daniel-thaly-87725195.html (accessed 8 August 2012).

6 Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, “Daniel Thaly: Poet of St. Pierre,” Repeating Islands, repeatingislands.com/2009/03/18/daniel-thaly-poet-of-st-pierre/, para. 1 (accessed 9 August 2012).

7 Daniel Thaly, Chants de l’Atlantique, suivis de Sous le ciel des Antilles (Paris: Garnier, 1928), 35–36 (translation mine).

8 Ibid., 35.

9 Ibid.

10 Lafcadio Hearn, “Two Years in the French West Indies,” in Christopher Benfey, ed., American Writings (New York: Penguin Putnam, 2009), 391.

11 Thaly, Chants de l’Atlantique, 36 (translation mine).

12 See Kevin Meehan and Paulette Richards, “Manmade Disasters: Viewing Mt. Pelée after Katrina and the Haiti Earthquake,” this issue of sx salon, http://smallaxe.net/wordpress3/discussions/2013/05/27/manmade-disasters/.

13 Aimé Césaire, Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, trans. Clayton Eshleman, ed., Annette Smith (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 2.

14 Honychurch, “Morne Pele Volcano and Dominica,” para. 18.