The Pleasures of Independence Literature

The Pleasures of Independence Literature

In the poem “Hope Gardens,” Lorna Goodison writes of the disjuncture between what a would-be poet learns in a seminar led by a postcolonial scholar and what she remembers of Hope Gardens in Kingston. Listening to the scholar reveal “plot / after heinous imperial plot buried behind / our botanical gardens,” the speaker can remember only the delights of picture taking, sky gazing, daydreaming in the gardens. Charming memories that inspire her to memorialize the gardens in verse; but this verse, and the pleasures it aims to record, is threatened by the scholar’s revelations about the pervasiveness of colonial power. Goodison closes the poem:

We the ignorant, the uneducated, unaware

That the roses we assumed bloomed just

to full eye were representative of English

lady beauty; unenlightened we were, so wepicked them on the sly to give as token

to the love we got lost in the maze with—

quick thief a kiss—and this colonial designwas nowhere in mind or sight; but even if

and so what?1

Goodison’s poem raises more than some simple question of ignorance being bliss. She pits pleasure against postcolonial enlightenment. Though she focuses on gardens here, I take her words as an opening to my discussion of pleasure to be found in Caribbean fiction published in the 1960s, the era of independence in the anglophone islands.

We don’t speak much about pleasure in the academy, as we choose “teachable books” for our classes and poetry upon which we can build soon-to-be-seminal articles. And when we do chose to do more than merely passingly acknowledge elements of pleasure experienced via text, it is primarily to analyze and categorize them as useful or not—for example, Roland Barthes’s distinction between pleasure (plaisir) and bliss (jouissance).

I am not advocating, by any means, a rejection of theory. Indeed, in my own classrooms I am often likely to be a literary version of that botanical postcolonial scholar in Goodison’s poem, expounding on the national notions of a novel or the postcolonial premises undergirding a poem. That very novel that my students may have enjoyed because it captured the bittersweet experience of love and loss; or that poem that spoke to the very heart of their personal struggles with their own families.

I raise this question of pleasure at this moment, however, when I am asked to reflect on the literature of independence because I wonder what makes such literatures, literatures invested in a particular historical moment, last beyond the moment of their creation. I venture to say what may seem obvious: that it is a combination of the pleasure the text gives the reader and the theory it engenders or illustrates for the scholar. It does not have to be one or the other, and this tension between pleasure and disciplinary practice may at times prove productive, but in thinking of the fiction of independence, I am interested in how the one might impinge on and enhance the other.

There are, of course, different types of pleasure when it comes to reading. Linton Kwesi Johnson’s “If I Woz a Tap-Natch Poet” names a few (along with poets he believes to be particularly good at providing these pleasures). There’s the “dyam deep” poem that causes a masochistic pleasure; there’s the “rootsy . . . rude . . . subversive” poem, with a rhythm that appeals to all generations even as its message calls for change (and LKJ’s poem itself would fit this category); and there is the pleasure of a Lorna Goodison poem, “soh beautiful dat it simple.”2 There is also the convoluted pleasure of something like a Wilson Harris novel, where the enjoyment of the text springs from trying to work out the puzzle of words. Certainly, what I find pleasurable reading is not necessarily what others find pleasurable, and those lines are often ideological and political, particularly in the classroom.

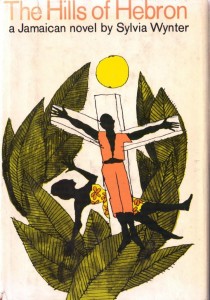

So let us say, then, that for the purposes of this essay, pleasures might be thought to be general, and where I give specific examples, I am thinking of my own sensibilities. I take as my primary example for this discussion Sylvia Wynter’s only novel, The Hills of Hebron. When I think of the literature of independence in the Caribbean, I immediately think of this novel. It is, for me, the überindependence text. As Shirley Toland-Dix succinctly states, “The Hills of Hebron is experimental, complex, and paradoxical, both epic narrative of the nation and critique of the extant vision of the nation.”3 The first edition of The Hills of Hebron, published in 1962, no less, had as its subtitle “A Jamaican Novel.” The novel has been published three times, first by Jonathan Cape and Simon and Schuster, then in the Longman Drumbeat series in 1984, and most recently in 2010 by Ian Randle Publishers. The “packaging” of each of these publications raises questions of why, and when we return to some narratives and how the pleasure we take—or are expected to take—in each iteration may depend on historical context. Below are covers from the 1962 (American), 1984, and 2010 editions, respectively.

In 1962, the book-jacket description places emphasis on the Jamaicanness of the novel and the symbolism of the characters, an emphasis reflected in the abstract yet ultimately individual figures on the cover. The jacket description ends by summarizing the kind of pleasure to be found in the pages of the novel: “As a Jamaican, Miss Wynter has firsthand knowledge of the people and the setting, but it is her artistry and her insight that give The Hills of Hebron its unusual and timeless quality.” In 1984, in keeping with the postindependence recognition of Caribbean literature as a potentially lucrative commodity for commercial publishers like Longman and Heinemann, the cover image and description stress the drama of sexual misconduct. The 2010 publication resituates the novel as an integral part of Jamaican literary history. With a cover image from Jamaican “master painter” Barrington Watson, as well as the academically oriented introduction and afterword, this edition is hyperaware of the import of The Hills of Hebron in discussions of independence fictions and returns the novel to the grandeur of a “Jamaica narrative.”

I borrow the term “Jamaica narrative” from Olive Senior’s keynote at the 31st Annual West Indian Literature Conference in October 2012. In conversation with Kei Miller, Senior spoke about writing during the independence moment in Jamaica. She explained that there was “an energy released at the time that shaped [Jamaican] writing” and that she felt herself to be “part of writing the Jamaica Narrative.” The term resonates deeply with how I view Wynter’s Hills of Hebron. She was indeed writing a Jamaica narrative in creating this religious would-be self-sufficient community in the hills of 1930s Jamaica. The struggles that the Hebronites encounter—natural, interpersonal, external, and financial—could at the time of publication and even now, fifty years later, be seen as predicting the troubles to come for the nascent nation of Jamaica.

As scholars and teachers, we often find ourselves relegated to writing and speaking primarily about the political import of texts like The Hills of Hebron that are positioned, or position themselves, as national narratives. This restriction can be exhausting, causing us to forget the pleasure we may have found in the text to begin with, the pleasure that new audiences may find there as well. Despite the overwhelming resonances with the historical moment and with Wynter’s later theoretical work, it is simply not fun to always and exclusively read the novel as a Jamaica narrative. Yes, it is impossible to overlook the connection to independence, but The Hills of Hebron also carries with it the pleasures of an entertaining tale. For example, there is the engaging mystery of Rose’s pregnancy. There may be some allegorical corollary between this mystery and the birth of a nation or such, but beyond the actual moment of birth at the end of the novel, it is difficult to sustain such a connection. Each time I read the novel, even knowing the end—or, perhaps, especially knowing the end—I look for clues to the adulterer, just as Obadiah does. I search Wynter’s language, her myriad tiny details, for indications of the guilty party. A second example: Wynter’s skill with character development. At times she delves into the secret yearnings of even the most peripheral characters, providing the type of rationale for action that makes it difficult to draw a distinct line between good and evil. There is more than a Jamaica narrative here. And as with all good novels, the complexities often speak to readers in different ways on each reading.

To be fair, however, there are aspects of pleasure in reading, studying, writing about, and teaching this novel that spring directly from its status as a novel of independence. The Hills of Hebron is rewarding because of its depiction of both the interpersonal and political intrigues, the plotting of both adultery and anticolonialism. The most interesting moments for me are those that are compelling both in their formal structure and in their contexts of production. A “both/and” appreciation that I imagine might parallel a space in the gardens of Goodison’s poem that one can relish because of and despite the paradox of its colonial design. One such moment in the novel is the scene between Prophet Moses and the Reverend Brooke, in the latter’s parlor:

They sat opposite each other in straight-backed mahogany chairs, separated only by a round table covered with a fringed cloth. The Prophet placed his Bible on the table. The parson sat waiting for the Prophet to say what he had come for; and adopted the defensive attitude that was peculiar to him—elbows on the armrests of the chair, his fingers loosely interlaced under his chin, his expression judicious. Moses clasped his fingers over his protruding stomach, crossed his feet and pulled them back as if to efface the bright gloss on his boots. His body was hunched in the chair with a subtle suggestion of deference, and he held his head tilted humbly, inquiringly. From the corners of his small, slanted eyes he watched the effect of his attitude on the man opposite.

The minister reacted at once. He felt a tight knot loosen inside him, felt his fear dissolve as the silence lengthened like the afternoon shadows in the room.4

This scene, filled with minute descriptive details of the setting and the two men’s perceptions of each other and themselves, can be read formally as a confrontation between two key characters in the book, pitting Moses’s slyness against Reverend Brooke’s privilege and arrogance. The balance of power continuously shifts during the conversation, and at the end, the self-delusions of each man leaves him believing he has gotten the upper hand. The passage can also be read in terms of the choreography of the Jamaican independence movement, with the two men representing Jamaica and England. In such a reading, the historical and political contexts of the novel provide additional layers of irony. It is the viability of both approaches to interpretation—and the pleasures to be found in each—that engenders the longevity of this and other fictions of independence that we continue to repeatedly read and teach today.

Kelly Baker Josephs is Associate Professor of English at York College/CUNY, specializing in World Anglophone Literature with an emphasis on Caribbean Literature. Her forthcoming book, Disturbers of the Peace: Representations of Insanity in Anglophone Caribbean Literature (University of Virginia Press), considers the ubiquity of madmen and madwomen in Caribbean literature between 1959 and 1980. She is editor of sx salon: a small axe literary platform and manages The Caribbean Commons site.

1 Lorna Goodison, “Hope Gardens,” in Kwame Dawes, ed. Jubilation! Poems Celebrating Fifty Years of Jamaican Independence (Leeds: Peepal Tree, 2012), 53–54.

2 Linton Kwesi Johnson, “If I Woz a Tap-Natch Poet,” Poetry Archive, http://www.poetryarchive.org/poetryarchive/singlePoem.do?poemId=14959. The Poetry Archive also includes an audio recording of LKJ performing this poem.

3 Shirley Toland-Dix, “The Hills of Hebron: Sylvia Wynter’s Disruption of the Narrative of the Nation,” Small Axe, no. 25 (February 2008): 58.

4 Sylvia Wynter, The Hills of Hebron (Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 2010), 196–97.