Nicholas Laughlin and Anu Lakhan discuss The Strange Years of My Life

Nicholas Laughlin and Anu Lakhan discuss The Strange Years of My Life

The Strange Years of My Life by Nicholas Laughlin (Peepal Tree, 2015) is a collection of contradictions and misrepresentations. The poems invite belief that the works are deeply personal: they are full of cuts, bruises, and loves; the workings of heart, mind, and blood; so many words, like nervous tics, that seem sensible only within the confines of the poems. But the poet would have you think differently. The people doing the feeling and thinking, they are not him; they are protagonists, antagonists, and, in at least one piece, rabbits. The poems have their little anxieties but they are also bold—almost reckless. But then, there really is no risk if the personae in the poems are all frauds or doppelgangers.

The first poem in the book begins with the phrase, “Don’t mention my name” (13). The populace of Strange Years is made up of aliases and false identities, disguises and alter egos, narrators who make suspect claims. I wonder if any of these characters actually tells the truth.

I have decided they are all honest to a fault. An alias is not a dishonesty; it is an option. So too alter egos. False identities and disguises are involved in the age-old literary tradition of masking. They are cousins to lies but less sophisticated. If, on any given day (any day except perhaps Carnival Monday or Tuesday), you leave your home wearing a Big Bird costume, it’s entirely possible that no one will know who you are, but aren’t you sort of begging to be asked? “Don’t mention my name” is the best way to start a rumor. These poems want to be asked the questions that will reveal their truths.

The conversation below is full of starts and stops. It took place over a few days of correspondence and more than twenty years of poet-interviewer banter. There is something here that speaks to a long habit of cutting across each other’s sentences but hopefully not so much as to mystify any reader. If there be non sequiturs or a sense of the arbitrary, consider: Do you really want the usual spiel?

Anu Lakhan: In “Everything Went Wrong,” the opening poem of the collection, this line appears: “Don’t trust the maps: they are fictions” (13). Are maps always fictions? Or anything that traffics in definitions—thesauri, history, directions to the local health center—are they all misleading? Is it their aim to confound you?

Nicholas Laughlin: Before you can answer that question you need to ask what is fiction.

AL: No, I really don’t think we do.

NL: Well, a map is a very particular kind of reference work, only a distant relation to a dictionary or an encyclopedia. Fixing our incomplete knowledge of the world into these kinds of structures, whether of images or words or both, is inevitably subjective, involves processes of imagination. So, yes, every map is to some greater or lesser degree invented.

Have you noticed that on maps, every river and lake is the same pristine shade of blue?

AL: A map fixes something in a particular time and space. You call a whole section of your book “Species the Maps Don’t Know.” Do you want maps to be vivified? To understand living things?

NL: A living map, whatever form that entity could take, would be a scary thing. But I guess Google is more than halfway to Frankensteining one. No, I love the idea that maps have their own language; I love them as physical artifacts, but I also love their inadequacies. They can’t describe what’s most essential about being in a strange place: the scent of wood smoke or eucalyptus, the way light falls and reflects and refracts in different landscapes, the elation of a horizon.

But, then, we all have “live” maps in our heads, in our memories and imaginations, constantly redrawing themselves as we learn new things or forget old ones. Our experiences change the colors and contours. A street corner that never seemed especially notable is suddenly traced in terrible gold because you see a particular person standing there.

***

Everything Went Wrong

Don’t mention my name in your letters.

Don’t write down my address.

In fact, better not write letters at all.

Better no one knows that you can write.

You’ll know not to drink the water.

You’ll know not to travel by night.

Don’t carry foreign banknotes.

Never give your name when you pay the bill.

You will need a shot at the border.

The needles are perfectly safe.

Yellow fever can’t be allowed to pass.

I knew a man who died in just three days.

The weather turned truly nasty.

It flooded ten miles around.

A boat capsized. A box was swept away.

I couldn’t afford to bribe the customs guard.

Don’t trust the maps: they are fictions.

Don’t trust the guides: they drink.

In this country there’s no such thing as “true north.”

Don’t trust natives. Don’t trust fellow travellers.

Better no one knows you sleep alone.

Already no one remembers you at home.

***

AL: As much as many poems are written in code—and one is especially suspicious of the ones that seem to be frank—yours are very much about pace and rhythm. They are lyrics for songwriters from the Beat era, and for the best rappers of today. How’d that happen?

NL: Funny, I thought I was writing lyrics for Satie’s piano works.

AL: Sometimes, when reading these poems, I tried singing them and realized that that worked very well.

NL: What tunes did you sing them to? Stevie Smith, if I remember it right, used to write poems to the melodies of Anglican hymns.

AL: I’ve taken to composing songs in my head, so they were mostly original compositions. Maybe some Killers and One Republic. Possibly Gym Class Heroes.

NL: Do you want a Strange Years playlist?

- Erik Satie, Gymnopédies; Croquis et agaceries d’un bonhomme en bois;Vexations

- Frantz Casseus, Suite No. 1 (Petro, Yanvalloux, Mascaron, Coumbite)

- Boby Lapointe, “Framboise”

- Franz Schubert, Piano Trio No. 2 in E Flat Major

- Richard Strauss, Four Last Songs (as sung by Gundula Janowitz)

- Heitor Villa-Lobos, Bachianas Brasileiras

- Rodgers and Hart, “My Funny Valentine” (as sung by Chet Baker); “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered” (as sung by Ella Fitzgerald or Anita O’Day)

- Ivor Gurney, “I Will Go with My Father a-Ploughing”

- Igor Stravinsky, Ebony Concerto

- R.E.M., “Strange Currencies”

- Bacharach and David, “Anyone Who Had a Heart” (as sung by Dionne Warwick)

- Matthaeus Pipelare, Een vrouelic wesen; Fors seulement

- Local Natives, “Wooly Mammoth”

- Billy Strayhorn, “Lush Life” (as sung by Johnny Hartman)

- Traditional, “If I Were a Blackbird”

- Traditional, “Río Manzanares” (as sung by Isabel and Angel Parra)

- Charles Ives, The Unanswered Question

AL: Delighted to have the mixed tape to your manuscript, but perhaps we might make our way back to the bedeviling matter of structures, intentions, and iterations of codes.

NL: The poems are written in language. Isn’t that tricky enough? “In code” suggests there’s a key the reader must find to unlock some hidden meaning. A poem’s meaning is the sound of the words and shape on the page, which aren’t hidden at all. But sometimes what a poem means is resistant to everyday modes of comprehension. And that’s why we read it: to be pushed or pulled into a relation with language, which is the world of the poem, more demanding and perhaps more illuminating than we might find in a newspaper.

AL: So, really, what you want me to accept is that the poems are not written in code.

NL: “Code” suggests a deliberation of composition that doesn’t resemble my own experience of writing poems. For me, a poem begins with a state of mental drift through the world that is language. There are limiting factors—the vocabularies and grammars available to me—and gravitational fields created by memories, predilections, habits, books I’ve read, music I’ve listened to. And I must be alert enough to actually write, but dreamy enough to not write too soon. And impatient enough to decide to stop at some point, because a poem must end somewhere.

I see I’ve sort of asked for this line of questioning, considering how many of the poems talk about cryptics, riddles, clues, languages the various narrators and characters don’t entirely understand, and so on.

AL: You think?

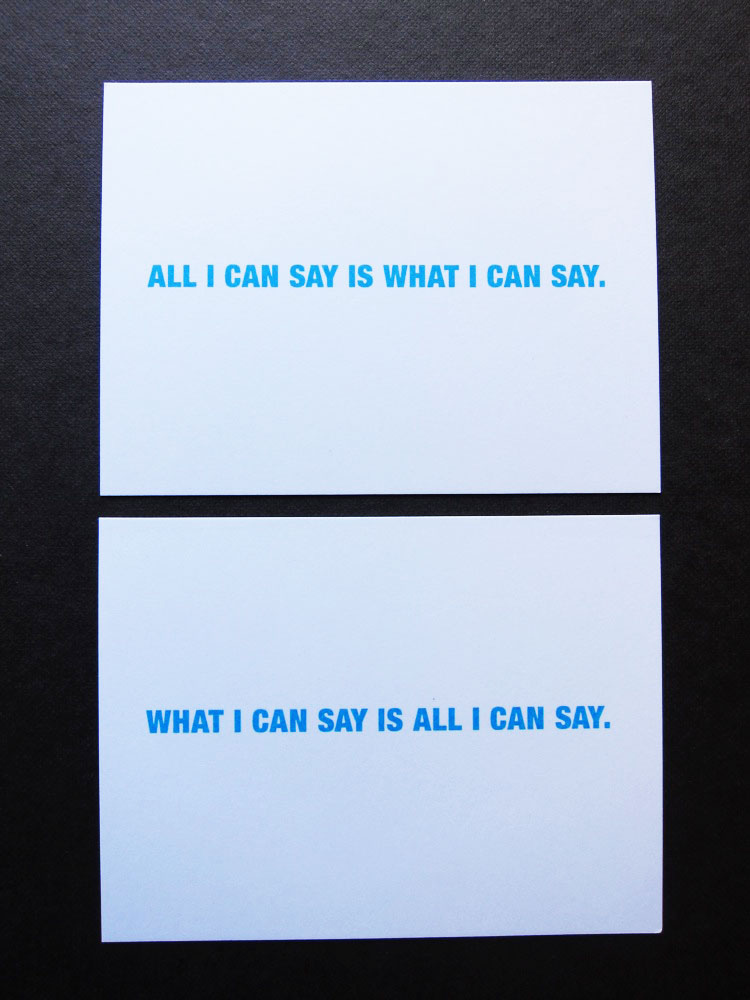

NL: Clearly I’m intrigued by the ways language communicates and doesn’t, by the idea of sayable and unsayable things, by the mysteries that are enfolded in even the most apparently plain phrases.

Maybe it’s a question not of codes but of aliases.

AL: “Unsayable things”: Why? What is it that consigns something to this category? Is it at all like a thing referred to as “unspeakable”? “Unspeakable” always suggests to me that here is a bit of information that you may not like, but nonetheless you really want to tell it.

NL: The American poet Donald Hall, in an essay I must have read twenty years ago and which I just found again, argues that the unsayable is exactly the subject of poetry. I mostly agree. In even the most ordinary hour of the most ordinary day, there’s so much of simply being that’s mysterious. So much of what we feel is inarticulate because inarticulable. Some writers take that for their subject, and those are poets.

(Alternative reply in visual form: www.flickr.com/photos/nicholaslaughlin/8097820887/in/album-72157627960685652/)

***

AL: What might allow the reader to come fearlessly closer? People who are very close—lovers, twins, parents and children—have their own languages. These are not necessarily consciously chosen (or, more playfully, they might be). Nonetheless, they exclude others. I think your poems have the potential to create a distance between themselves and the reader. For instance, there are specific references to things no one without a working web browser should even attempt to read.

NL: Maybe the poems also have the potential to create a distance between themselves and their author. Actually, I hope they do.

Every writer is making his or her own language, though—it’s part of what the textbooks call style. And what linguists call an idiolect, right? Perhaps to some readers it seems like a code—but, as you can tell, I want to resist that term and the implication that there’s a key of some sort. And I’d suggest there’s a value in distant reading too. It seems to me that a successful poem is a little object of language with multiple levels of meaning. One level of meaning is what the poet thought he was writing. Another is everything the poet didn’t realize he was writing. There’s the level of the mere sound of the words—haven’t you ever heard a poem read in a language you didn’t understand but still grasped something meaningful from the sound patterns?

I think one of the gifts of poetry is precisely the opportunity to be immersed in language that beautifully defies immediate and straightforward comprehension. Life is complicated and strange.

You know, Keats’s idea of negative capability is usually considered a description of the mental process of certain writers—Shakespeare was his example. But I’m drawn to the notion that it’s equally relevant to the experience of reading. “Being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason”—that’s a good way to read poems.

Anyway, I’m not in the truth business, I’m in the meaning business.

***

AL: I’m going to throw something at you here that cannot help but sound odd in the asking but comes from your creation of all these alter-egos. Also, you do have a poem called “My Prey, My Twin.” So, do you feel as though you have a twin and he’s been missing since birth?

NL: Not exactly. I’ve always wished I had a twin—I found myself saying this in public once, I’m not sure why—but it’s a wish with the knowledge of its impossibility. I suppose it’s one of the little excruciations that lie behind the “small husband” poems at the end of Strange Years.

AL: What is a small husband?

NL: Billie Holiday sang “Don’t explain”—better advice for poets than for unfaithful lovers.

The small husband is an alter ego who is also a nemesis or adversary, apparently in the form of an animal familiar: a wren. There’s an ancient fable about how the tiny wren came to be called king of the birds (spoiler: he’s a smartman), and in several languages the common name for the wren is “little king”: roitelet in French, reyezuelo in Spanish, and so on. I don’t know why I decided to call mine “small husband”—the phrase just appeared in my head and seemed right. The Greeks blamed the Muses for this sort of apparition.

In his Birds of Trinidad and Tobago, Richard ffrench lists “God-bird” as one of the local vernacular names for the house wren, Troglodytes aedon. I just wanted to throw that in.

AL: Small husbands cause ache and longing and the feelings that make you long for a poison-tipped knife. Or one kiss. And really, all you’re going to talk about is wrens? No disrespect to wrens.

NL: Just giving you the facts, ma’am. My small husband is a cruel little deity perhaps torn from my own flesh, who happens to manifest with wings and eyes and small claws. Poems ensue.

I’d love to think that different readers imagine him in different ways, project their own peculiar longings and losses into him.

***

AL: The unsettling thing about this collection is that in spite of their strangeness, but certainly not because of it, the poems, the players, are familiar. Who has not missed a friend she did not yet have? Have we all not been wanted and disowned? So, if you take the time to let it breathe, maybe let the words take a turn around your head, you might find that a poem has spotted you and can take you down at twenty paces.

NL: I hope so. I’ve long thought that the ideal for a poem is to seem both improbable and inevitable at the same time. A poem should trouble its reader’s sense of mental privacy—how did you know?

I’ve been rereading Yeats and came upon this in one of his essays: “I print the poem and never hear about it again, until I find the book years after with a page dog-eared by some young man, or marked by some young girl with a violet, and when I have seen that I am a little ashamed, as though somebody were to attribute to me a delicacy of feeling I should but do not possess.”1

AL: Yeats has the measure of it.

***

My Prey, My Twin

Little king, my prey, my twin,

trail of pearls in the grass.

Glass bones in my wrist.

Pulse in a maze of glass,

All throat and eye

and wrist and spy,

electric ribs.

Trick as a trap.

My nettle tongue prickled with a pledge.

The crook of my arm pricked with the pulse of a bird.

***

AL: I found this note in pencil, must have written it awhile back:

“p 78—can’t decide if the last lines of many of these poems are nervous endings or bravado.”

What do you think?

NL: Robber talk.

AL: I see. Brash and hyperbolic; promising brimstone and blood; all things larger than life, all lies—but wishful thinking ones—all spoken by a Carnival character meant to menace but really looks like the hat he got for Christmas is too big.

Anu Lakhan is a writer, editor, and publishing triage consultant living in Trinidad and Tobago. She is the editor of Macmillan’s Caribbean Street Food series as well as the author of the Trinidad and Tobago volume. Her reviews, essays, poems, and short stories have appeared in the Caribbean Review of Books, Caribbean Beat, Wasafiri, and Bomb. Two years ago, she and journalist Robert Clarke established Clarke & Lakhan, a publishing company.

Editor’s note: Continue the exploration of Nicholas’s poems with his “Lagniappes,” which he describes as “A series of small printed objects intended to hover near, or be inserted into the pages of, The Strange Years of My Life; outtakes, extras, interruptions, distractions.”

1 William Butler Yeats, “The Bounty of Sweden,” in The Collected Works of W. B. Yeats, vol. 3, Autobiographies, ed. William H. O’Donnell and Douglas N. Archibald (New York: Scribner, 1999), 392.