Literature and the Sir George Williams University Protest

Literature and the Sir George Williams University Protest

Figure 1. Students protesting, with punch cards, thrown from the windows of the ninth-floor computer center, covering the ground.

Image Source: Concordia University Records Management and Archive (File 1074-02-150)

A burning issue inspires this discussion. We begin by raising the oft-considered question, Why has the so-called Sir George Williams affair—the university student protest of 1969—received so little attention? Even more specifically, we ask here, Why has it not been the basis of more literary volumes and narratives? Indeed, as Kamau Brathwaite has pointed out, Caribbean protests of the period produced significant creative outputs.1 Yet when this protest by West Indian students and their allies in Montreal is narrated, it is primarily by historians. Certainly, there are many details to capture the narrative imagination. This student-led protest against racism began with a complaint by six black West Indian students against a white professor in the spring of 1968. After the failure of the administration to adequately address their concerns, the occupation ensued in the winter of 1969—the student takeover of the university’s state-of-the-art computer center was sustained for two weeks, lasting from January 29 to February 11, during which time anywhere from three to five hundred students and allies, both black and white, were involved. The events unfolded at a dramatic moment in the civil rights struggle, in the months following the historic 1968 Congress of Black Writers and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Indeed, while the students at Sir George protesting against discrimination in grading practices were being closely monitored by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the US Federal Bureau of Investigation, King’s killer hid in Toronto for nearly a month, undetected by investigative forces.2 The sit-in ended in a mysterious fire that resulted in $2 million worth of property damage, as documented by insurance photos in the archives. Not held in the archives but rather carried in memories are the experiences of students fleeing the fire who were forced to hack their way to safety with an emergency axe, directly into the path of waiting police who led them out at gun point through crowds chanting racist slurs.3 Ninety-seven students were arrested; arson charges carried the risk of deportation or even life in prison. The incident radiated outward, as witnessed in fundraising efforts within the black Montreal community, in the protests in the Caribbean in support of the arrested students (which led to the formation of the National Joint Action Committee in Trinidad, a Black Nationalist political party), and in the diplomatic intervention by Prime Minister Eric Williams, who paid the fines of the ten Trinidadian nationals arrested.

Figure 2: Insurance photo of ninth-floor property damage, 1969.

Image Source: Concordia University Records Management and Archive (File 1074-02-049)

In as much as contributors to this issue of sx salon reflect on and discuss literature that has been produced about the student occupation of Sir George Williams University (SGWU), the essays here also mobilize an urgent call for more writing, whether in fiction or nonfiction, narrative or poetry. In attending to the question of literary silences, Stéphane Martelly, in an essay about the young protester Coralee Hutchison who died after being struck with considerable force by a police officer, notes how the possibility of silence and erasure meets the looming specter of death with the ongoing passage of time in which narratives and stories have not been committed to the page.4 Reflecting on the Sir George Williams affair through the framework of embodied archives and focusing on questions of aging, memory, mourning, and temporality with the protest now fifty years in the past, Martelly observes, “What is left is silence and the fading but heavy memories of people who are now older men. . . . Yet the silence is powerful and persistent.”5

In centering a focus on literature in relation to the SGWU protest, we would like to point out that writers were present. The Trinidadian novelist and artist Valerie Belgrave, for instance, was one of the ninety-seven students arrested.6 Fellow Trinidadian poet and storyteller Paul Keens-Douglas was also among the Caribbean students at Sir George in 1969, but to date he has not written extensively about that particular chapter of his life. This leaves us to wonder what his characters—Tanti Merle, in her riotous, irreverent mode of storytelling, or Tim Tim, Slim, or Tall Boy—might have to say about what happened at Sir George.

Caribbean writers at the time were keenly aware of the protest. C. L. R. James, of course, was central to events in Montreal in 1969. Black students in Montreal had previously organized a reading group called the C. L. R. James Study Circle (CLRJSC), where they read and discussed his work and that of other black political writers. James had attended the 1968 Congress of Black Writers in Montreal, and as Philippe Fils-Aimé notes, during the occupation the students were in constant contact and dialogue with James, receiving encouragement and advice and discussing strategy.7 Brathwaite, writing in his 1976 essay “The Love Axe (1): Developing a Caribbean Aesthetic,” in which he talks about revolution and Caribbean consciousness in the context of the writings of Paule Marshall, George Lamming, Wilson Harris, V. S. Naipaul, and Austin Clarke, among others, hails the Sir George Williams affair as part of a constellation of events that mark the development of a Caribbean consciousness and aesthetic in the context of universities as a site of knowledge and struggle. Contextualizing the February 1970 student occupation of the Creative Arts Centre at the University of the West Indies, Mona, which unfolded a year after the events at Sir George and in which the occupying students “demand[ed] the West Indianization of the cultural events,” Brathwaite calls on the Sir George Williams affair to situate the terror and the tenacity of the time: “Here at last you might say was our Sir George William [sic], our Cornell, perhaps our Kent State—for there were rumours throughout most of the occupation (February–April 1970) that the police were going to be asked to intervene. . . . One militant even cried out that we should seize the Computer Centre.”8 In Brathwaite’s rendering, the student protest at Sir George not only functions as a site of comparative discussion but also emerges in his brief analysis as inspiration, as tactical example, and as a site of interconnected, transnational struggle.

However, we want to additionally call attention to the fact that Brathwaite positions Sir George within and as part of a specific discussion about “developing a Caribbean aesthetic.” While others have emphasized the protest’s transnational and geopolitical significance, Brathwaite situates it within a discussion of aesthetic politics and possibilities.9 Brathwaite’s focus on Caribbean creative aesthetics was extended by Kaie Kellough’s reflections in a recent lecture given at the Powerplant in Toronto, in which he described the protest as “rife with narrative possibilities” and in terms of narrative multiplicity and polyphony:

The form that I perceive . . . is a kind of hub whose metaphysical spokes radiate outward across the country, overseas, and across time. . . . All of its stories can never be told, all of the people who were moved by it, and perhaps emboldened and shaped by it are still being counted.10

This attention to multiplicity and to creative possibilities has been further extended by historian Michael O. West, in his observation that “an event capable of causing such a thorough nomenclatorial erasure [in the renaming of the university] also has the capacity to create other fables.”11 We also note how the multiplicity of terms used to refer to the event demonstrate an array of narrative possibilities and perspectives. It has been variously called “the Sir George Williams affair,” “the Sir George Williams University protest,” “the Sir George Williams University occupation,” “the Sir George Williams computer center occupation,” “the computer center riot,” “the computer center incident,” “the computer center party,” “the crisis at Sir George”—each name containing and revealing different political, perspectival, cultural, and ideological investments and formulations.12 Throughout the essays in this issue, authors employ different terms as part of their own narration of the event. The essays published here, then, might be situated as part of an ongoing exploration of the aesthetic terms, potential, resources and the story forms of what we might call the Sir George narrative—a branching network of questions, dialogues, and reflections traced across history, literature, sociology, and journalistic accounts.

In his essay contribution to this discussion, H. Nigel Thomas offers a survey of the literature that has been written about the protest.13 He focuses in particular on drama and narrative fiction as two primary literary genres that have served in creative accounts of the story of Sir George. However, we also want to attend to, in more layered terms, the question of different modes of scripting the event. Situating the three discussion pieces included here within the broader archive, we want to briefly explore how each might be read in terms of an attention to one of three different but interrelated narrative scriptings and imaginings of the protest—romance, tragedy, mystery—and how, in turn, each operates as part of a complex, unsettled story of what happened at Sir George.

Our thinking in this regard draws on David Scott’s Conscripts of Modernity, in which he reads C. L. R. James’s writing of the Haitian Revolution in The Black Jacobins first in terms of romance and then of tragedy.14 We argue that romance and tragedy as discussed by Scott might also inform readings of the scriptings of the Sir George protest. In raising this question and in framing this discussion through Scott’s work, we situate the events in Montreal in relation to the legacies of James but also in relation to Haitian anticolonial thought, revolution, and protest. This is not to claim that the 1969 protest in Montreal was of the same epic significance or scale as the grand revolt in Haiti, but rather that Haitians’ spirit of insurrectionist protest and the attempt to negotiate other horizons of sovereignty might be glimpsed in the black students’ protest and resistance. In fact, as David Austin notes in his essay in The Black Jacobins Reader, “Members of the CLRJSC [in Montreal] read the The Black Jacobins with the Caribbean in mind . . . as they attempted to chart a course towards Caribbean liberation in the 1960s and 1970s.”15

An investment in romance as a way of emplotting the 1969 protest can be glimpsed in Thomas’s reflections on the event. Our discussion of romance here is informed by Scott’s specific articulation of romance in the context of Hayden White’s “theory of the poetics of historiography”: “Romance, [White] says . . . ‘is a drama of the triumph of good over evil, of virtue over vice, of light over darkness, and of the ultimate transcendence of man over the world in which he was imprisoned. . . .’ Romance, in short, is a drama of redemption.”16 Indeed, if The Black Jacobins, as Scott posits, “was written as a complex response to a complex demand for anticolonial overcoming,”17 such an investment can also be observed in Thomas’s discussion of 1969 within the broad narrative arc of the dialectic between slavery and freedom. In his opening paragraph, Thomas argues that the event plays out a long historical tension: “How do blacks respond to the servile roles that a majority-white society seeks to force them into?”18 By placing the events in this framework, the protest can be understood as a story of anticolonial uprising and as fundamentally imbued with an insurrectionist ideal and an investment in decolonial future possibilities.

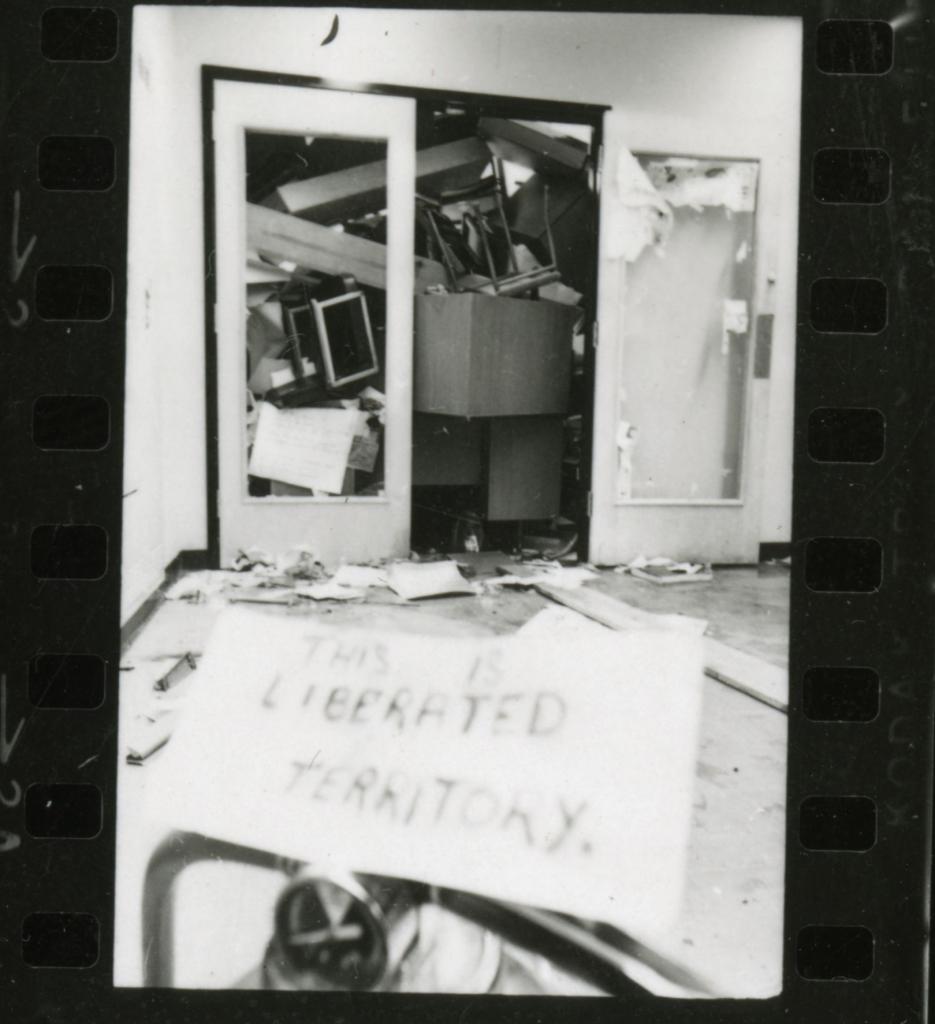

Figure 3: Barricaded room, with a sign a reading, “This is liberated territory.”

Image Source: Concordia University Records Management and Archive (File 1074-02-119)

Thomas’s framing of the story of the Sir George protest in this way might also be further understood through his referential turn to Shakespeare’s The Tempest as the ur-narrative for the unfolding conflict. Reflecting on the backlash in the wake of the protest, Thomas argues that “comments [by white Canadians] implied that blacks did not belong in the university, that the destruction of the computers was proof that they were impervious to the blessings of civilization, that in essence they were and would remain Calibans.”19 Thomas’s invocation of Prospero and Caliban echoes Scott’s own insightful analysis of Lamming’s refiguring of James’s Toussaint Louverture “in the image of Shakespeare’s Caliban: Caliban, as [Lamming] says, ordering history, resurrecting himself ‘from the natural prison of Prospero’s regard.’” As Scott further notes, “This interleaving of The Black Jacobins and The Tempest has been enormously compelling, partly because it captures so vividly the fact that the encounter between Africa and Europe in the New World was structured by power.”20 It is this relationship of power to which Thomas is most attentive in his discussion of the contestation and refusal of “the European figuration of African peoples as beasts of burden.”21 This attention to power is also traced in Kaie Kellough’s analysis here of the ending of Thomas’s Behind the Face of Winter. Kellough examines the political function of apologies and reparations and shows how Thomas’s novel restages the broad details of the SGWU protest but with two significant changes: first, the drama unfolds in the context of a high school, and, second, the episode is resolved through an apology.22 While no apology has yet been offered by the university or the police in the aftermath of the Sir George Williams affair, fifty years on, we might in fact argue that it is Thomas’s investment in what Scott terms “a narrative of revolutionary overcoming” that leads to his rescripting of outcomes and his vision of reparative justice as a possibility.23

Alongside this, we turn again to Stéphane Martelly’s reflections on the protest and the literary silences hence. Her essay here is a moving and focused scripting of tragedy—the second of the three modes—in which she remembers and mourns the life of Coralee Hutchison, a fatality of the protest. Martelly also attends to Coralee in a contribution to the “Poetry and Prose” section of this issue, where she not only outlines the tragic loss of young life but also performs a call for mourning by titling a suite of poems written for Coralee “Neuvaine” (translated by Kaie Kellough as “Novena”).24Neuvaine comes from the Latin novem (“nine”) and is a practice of public or private devotional prayer repeated for nine successive days or weeks.25 Martelly’s use of the oral verse form of devotional prayer engages with mourning and memory of what happened on the ninth floor of the Hall Building at Sir George; it is a call to public memorial. The poem performs a kind of “wake work,” much like Christina Sharpe theorizes—”Wakes are processes; through them we think about the dead and about our relations to them”26—honoring our relations to the dead within ceaseless conditions of antiblackness, past, present, and future. Indeed, beyond its scripting of the individual tragedy of Coralee Hutchison, Martelly’s work offers an opening through which to contend with the tragedies of settler colonial violence in the ongoing brutal suppression of protest (specifically in Canada, through the state arm of the RCMP) and invites us to contend with both the foreclosing of possibilities of real revolutionary change and the ongoing disposability of black and indigenous lives and voices.

While romance and tragedy are the two modes of emplotment that Scott examines in his revaluation of James’s The Black Jacobins, it should be noted that he also points us toward a consideration of other narrative modes and formulations. “Any given historical account,” Scott significantly argues, “is likely to contain stories cast in one mode as aspects or phases of the whole set of stories emplotted in another mode.” In his examination of Hayden White’s poesis on history, Scott notes that White “acknowledges that there may be others, epic for instance, or pastoral.”27 In turning to Kellough’s fictional narratives about the 1969 protests, we propose that his stories conjure and enact a third mode of emplotment in relation to these events, that of mystery. In pointing to this third mode we suggest that Kellough does not reject the first two but rather adds to them; romance, tragedy, and mystery become overlaying modes of black diaspora revolutionary stories.

In his work, Kellough draws on the forms of the detective narrative and the thriller to insist on an investigative imperative as part of the telling of the story of the 1969 protest. Thomas observes this in his discussion of how Kellough’s stories invoke Hamidou, a minor character in Hubert Aquin’s spy thriller Prochaine épisode.28 In Kellough’s story “Ashes and Juju,” every year on the anniversary of the students’ arrests, Hamidou, a former spy who is now a shopkeeper in Montreal, dreams of making a film about the protest. However, he grapples with how to tell the story, with its complex and missing parts as well as its still-unknown intrigues. At the level of narrative form, he can only imagine the film as potentially “an ungainly hybrid of psychological thriller, horror and historical documentary.”29 Kellough, in this regard, explicitly invokes the question of emplotment as part of his narrative. His self-conscious foregrounding of the question of form as narrative problem responds to the fact that even in the telling of the SGWU protest as history, specific details remain murky.

At the Protests and Pedagogy conference and series of events convened in February 2019 at Concordia University to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the protests, the historian Michael O. West, as part of the conference’s proceedings, called for the university to convene an inquest to investigate details of the event. In his work, West has also approached the events at Sir George with a series of questions interrogating details about who set the fire—its origins and causes. The narrative of the leadership of the occupation also becomes reframed in West’s work as a historiographical question to explore the “oft-existing gap between history and historical memory, between perception and reality.”30

In Kellough’s story, the investigative imperative in the end comes to rest not so much with Hamidou, the retired spy and double agent from the 1960s, but with one of the customers who frequents the shop that he now operates—a young graduate student named Tamika who is completing a dissertation on the Grenada Revolution and who writes a paper on the fortieth anniversary of the 1969 occupation that calls attention to and examines the maps of the ninth floor of the Hall Building before the university’s renovations. Here Kellough not only references the work of decolonizing history but also, in this attention to intergenerationality, raises possibilities for “decolonizing futures” explored in the closing discussion piece between Raphaël Confiant and H. Nigel Thomas. Kellough’s story itself reproduces this map, asking us as readers to look at it both as material evidence and as motivation for further inquiry. Yet the intergenerational meeting of Hamidou and Tamika that the story narrates is not so much a straightforward moment of exchange in which one generation tells the story to another, creating any definitive version or account. Rather, Kellough’s “Ashes and Juju” engages and invites the possibility of further inquiry, questions, and investigations, both creative and critical. It suggests that this must necessarily take place across generations and across genres (in this case, history, fiction, and film). It also imagines possibilities for a process and praxis of dialogue between those in the academy and in the wider cultural public, as well as creative cross-fertilizations between visual and narrative texts in the service of re-membering the “virtiginous narrative” of the SGWU protest.31

Ronald Cummings is an associate professor of postcolonial studies at Brock University. Nalini Mohabir is an assistant professor of postcolonial geographies at Concordia University. They were both part of the organizing team for Protests and Pedagogy, a conference and two-week series of events at Concordia University marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Sir George Williams University protest. The 2019 events were held to coincide with the duration of the protests, 29 January to 11 February. The authors are currently coediting a volume about the 1969 protest titled The Fire That Time: Transnational Black Radicalism and the Sir George Williams Occupation (Black Rose, forthcoming).

1. Edward [Kamau] Brathwaite, “The Love Axe (1): Developing a Caribbean Aesthetic 1962–1974,” in Houston Baker, ed., Reading Black: Essays in the Criticism of African, Caribbean, and Black American Literature (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1976), 22. We also note how later protests, such as those in Brixton in the period of the 1980s, have been the focus of different literary accounts.

2. See David Austin, Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex, and Security in Sixties Montreal (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2013). See also Steve Hewitt, Spying 101: The RCMP’s Secret Activities at Canadian Universities, 1917–1997 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), and Robert Benzie, “How Toronto Concealed King’s Killer,” The Toronto Star, 5 April 2008, https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2008/04/05/how_toronto_concealed_kings_killer.html.

3. See Valerie Belgrave, “The Sir George Williams Affair,” in Selwyn Ryan and Taimoon Stewart, eds., The Black Power Revolution of 1970: A Retrospective (St. Augustine, Trinidad: University of the West Indies Press, 1995), 129. See also Dennis Forsythe, Let the Niggers Burn! The Sir George Williams University Affair and Its Caribbean Aftermath (Montreal: Black Rose, 1971).

4. On Hutchison’s death, see Austin, Fear of a Black Nation, 136–37.

5. See Stéphane Martelly, “Writing to / for / with Coralee,” this issue of sx salon.

6. See Valerie Belgrave, “Memories of a Hot Winter,” Caribbean Review, 3 August 2017, https://www.caribbeanreview.org/2017/08/memories-hot-winter/.

7. Fils-Aimé spoke about this at Protests and Pedagogy, a conference and two-week series of events held at Concordia University in 2019 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Sir George Williams affair. His remarks will be published in our edited volume The Fire That Time: Transnational Black Radicalism and the Sir George Williams Occupation (Montreal: Black Rose, forthcoming).

8. Brathwaite, “The Love Axe (1),” 24.

9. See, for instance, representations of Canadian imperialism in Forsythe, Let the Niggers Burn!

10. Kaie Kellough “Fire in the Mainframe” (performative lecture, 19 October 2019, the Power Plant, Toronto); see https://vimeo.com/370936183.

11. Michael O. West, “History vs. Historical Memory: Rosie Douglas, Black Power on Campus, and the Canadian Color Conceit,” Palimpsest 6, no. 1 (2017): 84.

12. For different referential terms for the 1969 protest, see, for example, Dorothy Eber, The Computer Centre Party: Canada Meets Black Power (Montreal: Tundra, 1969); Dennis Forsythe, ed., Let the Niggers Burn! The Sir George Williams University Affair and Its Caribbean Aftermath (Montreal: Black Rose, 1971); and Renée Morel, dir., Crisis at Sir George, DVD, 48 min. (Moncton, New Brunswick: Connections Productions, 1988).

13. See H. Nigel Thomas, “Hamidou’s Crossroads: Kaie Kellough’s Fictional Meditation on ‘the Sir George Williams Affair’ in Dominoes at the Crossroads,” this issue of sx salon.

14. David Scott, Conscripts of Modernity: The Tragedy of Colonial Enlightenment (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004).

15. David Austin, “The Black Jacobins: A Revolutionary Study of Revolution, and of a Caribbean Revolution,” in Charles Forsdick and Christian Hogsbjerg, eds., The Black Jacobins Reader (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 272.

16. Scott, Conscripts of Modernity, 46, 47. Scott quotes Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973), 8–9.

17. Scott, Conscripts of Modernity, 10.

18. Thomas, “Hamidou’s Crossroads.”

19. Ibid.

20. Scott, Conscripts of Modernity, 15.

21. Thomas, “Hamidou’s Crossroads.”

22. See Kaie Kellough, “Confounding the Void: The Sir George Williams Computer Center Occupation in H. Nigel Thomas’s Behind the Face of Winter,” this issue of sx salon; H. Nigel Thomas, Behind the Face of Winter (Toronto: TSAR, 2001).

23. Scott, Conscripts of Modernity, 19.

24. Martelly, “Writing to / for / with Coralee”; Stéphane Martelly, “Neuvaine,” translated by Kaie Kellough as “Novena,” this issue of sx salon.

25. Throughout the Caribbean there is the funerary tradition of the Nine Night, for which mourners gather over nine nights to mourn the departed and perform rites to ensure the resting of their spirit. This has roots in African Caribbean religious practice.

26. Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 21.

27. Scott, Conscripts of Modernity, 47.

28. Thomas, “Hamidou’s Crossroads.”

29. Kaie Kellough, “Ashes and Juju,” in Dominoes at the Crossroads (Montreal: Vehicule, 2020), 169.

30. West, “History vs. Historical Memory,” 87.

31. Kellough, “Ashes and Juju,” 169.