Reflections on Transfer One Hundred Years On

Reflections on Transfer One Hundred Years On

The sale and transfer of St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John from Denmark to the United States on 31 March 1917 marked a sea-change for these islands. In that moment, they changed hands from a far-flung European landlord to a more proximate American owner. In retrospect, and given the magnitude of the effect the sale would have on these islands, their transfer can seem a foregone conclusion: the Virgin Islands was always going to be under the American flag. Virgin Islanders were always going to be at least partially American. Yet accounts from 1917 show that there was much confusion, rumor, and chaos surrounding the day of transfer itself. An editorial in the 30 March 1917 edition of the West End News, a newspaper then published in Frederiksted, St. Croix, summarized this lack of clarity, noting, “Even the officials says [sic] they are without instructions as to whom or how or when to deliver the islands. . . . As the mails as usual on account of bad wind did not reach in time with mail from St. Thomas, which presumably should contain something about tomorrow, we are still fumbling about like dumb beasts.”1

Beyond the drastic change in proximity there were other transformations—and expectations of change—that came with the ostensible incorporation into their new nation, the United States. At the time of transfer, Virgin Islanders hoped to become fully fledged citizens of the United States and distance themselves from their former Danish slavemasters. In Land of Love and Drowning, Tiphanie Yanique writes of this hope of inclusion on the part of Virgin Islanders:

In America, they have a dream. People from all about the place come together and now they is one nation. It dougla-up, just like the Caribbean. Correct? And the island intellectuals who was writing then, they thinking is only a matter of time before all of we Caribbean going to be part of the United States and then the United States, with the Caribbean as a figurehead, like what on ship, going to be a shining beacon to the free world. That what some fools was thinking on Transfer Day. . . .

. . . And you could see even now from the pictures in the archives, how them men looking sharp in their military uniforms. Gold buttons glinting. Mama could see that freedom does be well-dressed and fashionable. And that’s what happen. Danish West Indies become United States Virgin Islands. And just so, we go from Danish to American like it ain nothing. Like it ain everything.2

This notion of the Caribbean—the Virgin Islands—serving as a “figurehead” of the United States was quickly dashed by the realities of being absorbed into a country squarely in the midst of the Jim Crow era and grappling with own its racial hierarchy. The same edition of the West End News contains a summary of lynchings that took place in the United States, with a breakdown by race, gender, and offense (the period from 1 January to 1 November 1916 saw fifty-five). It would take more than a decade for residents of these islands to be granted American citizenship, and even this gesture toward inclusion was a far cry from comprehensive, as Virgin Islanders remained (and today remain) ineligible to vote in American presidential elections, rendering them effectively voiceless in the selection of the leader of their new nation.

In many ways, the transfer was “everything,” as Yanique writes. Much has been written about the dramatic change in the racial order on these islands under the Americans, with a general sense that the Danes had been relatively lenient—some have even argued progressive (e.g. the work of Jens Larsen)—vis-à-vis their views on race.3 In his analysis of Danish colonialism, Gordon Lewis takes up this overly-generous assessment: “Much has been made of the liberal quality of Danish rule. To some extent, that was so. Denmark was the first European nation to abolish the slave trade. Danish official policy actively fostered the social elevation of the free colored elements, even going so far, in the remarkable royal edict of 1831, as to permit the legal registration of colored persons as white citizens, on the basis of good conduct and social standing.”4

Norwell Harrigan and Pearl Varlack also argue that “the Danes attempted to be less ruthless than some other colonial powers (for example, nothing could raise blacks to the status of human beings in the eyes of the English and the Dutch).”5 Yet, this relative moderation is hardly exculpatory, as Danish slave owners regularly inflicted punishments, including mutilations, public whippings, and amputations, as demonstrated, for instance, in the work of Neville Hall.6 An example: material from the Danish National Archives details the punishments meted out to several enslaved persons who attempted to escape during an uprising in the Danish West Indies, including one whose corpse was paraded around the island behind a horse before being “hung [sic] from the gallows and finally burned on the bonfire.” Several of his fellow attempted escapees were similarly tortured: “Some were placed in a small iron cage in the burning sun and did not die for several days. Others were pinched with red-hot tongs and then burned alive on bonfires or hung up by the legs before they were finally choked to death. The two leaders were broken on the rack and placed alive on the wheel, where they remained alive for two hours and twelve hours, respectively.”7

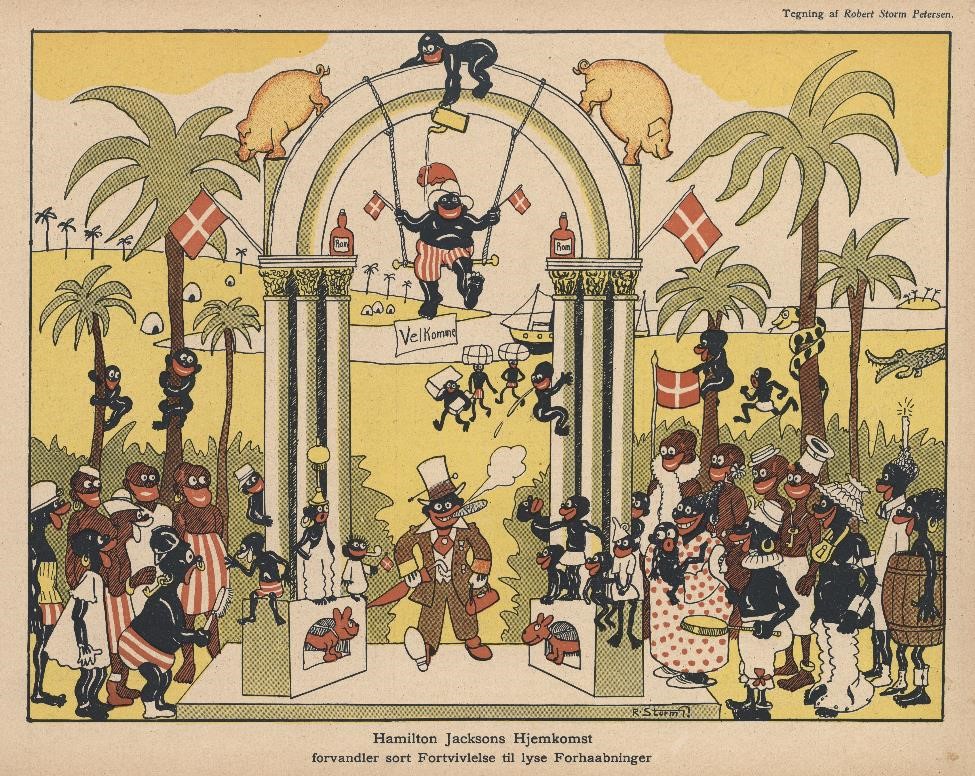

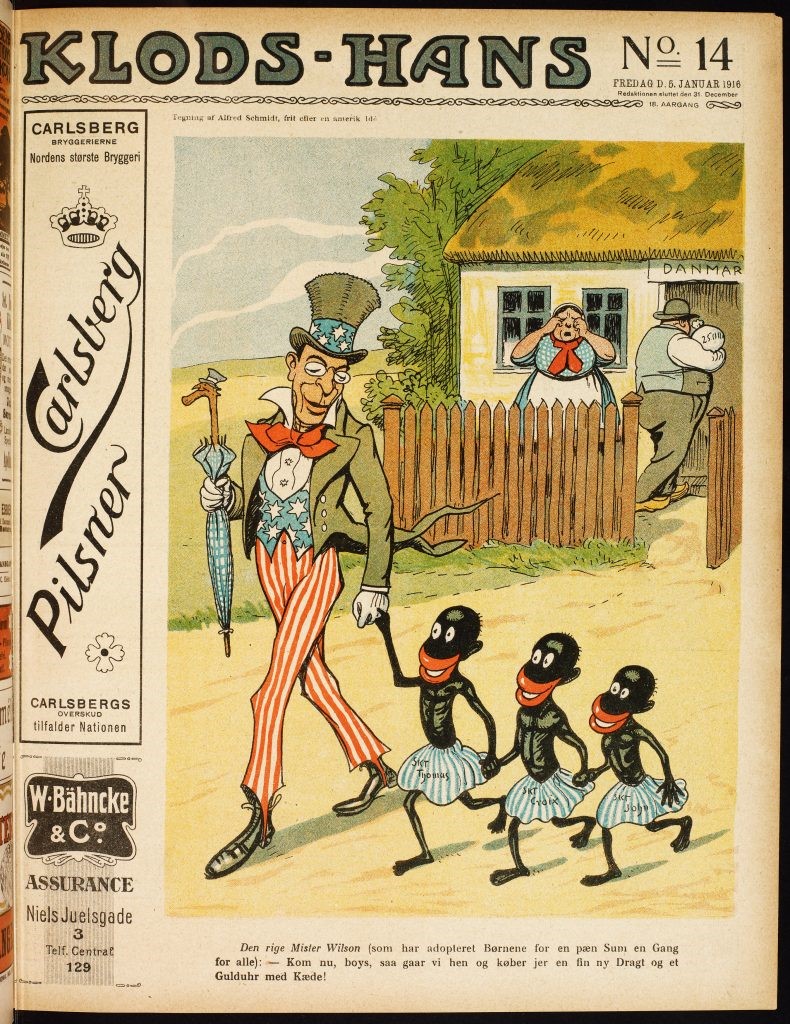

In the period following slavery, the Danes continued to mark black people, and particularly Danish Caribbean subjects, as inferior and hapless. For instance, Caribbean labor leader and publisher D. Hamilton Jackson was widely mocked in the Danish press for his visits to Copenhagen during which he attempted to advocate for the black residents of the Danish West Indies (see fig. 1). Danish illustrations of the transfer of the islands to American rule also feature these racist caricatures (see fig. 2).

Figure 1. David Hamilton Jackson’s return from Denmark in 1915, as satirized in the magazine Svikmøllen. Robert Storm Petersen, "amilton Jacksons (sic) hjemkomst forvandler sort fortvivlelse til lyse forhåbninger." Retrieved from the Royal Danish Library, kb.dk/images/billed/2010/okt/billeder/object302777/en/

Figure 2. In this caricature from the magazine Klods-Hans, President Woodrow Wilson leaves with the three small islands in the form of three black boys, while the sack of money is carried into the Denmark House and Mother Denmark weeps bitter tears over the loss.Alfred Schmidt, in Klods-Hans, 1917. From The Danish National Archives’ digitization project “The Danish West Indies – Sources of history.” virgin-islands-history.org/en/history/sale-of-the-danish-west-indian-islands-to-the-usa/our-new-west-indian-fellow-citizens/

None of this particularly villainizes the Danes. Rather, they—like their European slaveholding peers—were actively engaged in ruining the lives and limbs of those who stood in the way of their plantation profits. Or, as Peter Hudson has described the banality of racism in that period, these punishments and caricatures were “in many ways an unremarkable product of [their] era.”8 This history and relationship to Denmark makes clear why there would be some excitement on the part of island residents surrounding new possibilities under the American flag.

With the purchase of the former Danish West Indies, the United States owned what Harrigan and Varlack have called its “first black colony.” In their work, they argue for the particularity of the Virgin Islands as a “black” possession of the United States:

The United States had become a colonial power several decades earlier (the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam were ceded by Spain in 1898; Hawaii became a territory in 1900), but the traditional “white man’s burden” had assumed another dimension with the purchase of the Virgin Islands—a black colony. And while it is true that blacks were a depressed and despised minority in several states of the Union, America had neither previous experience nor adequate preparation to deal with the task involved in the new undertaking.9

As it would happen, the United States soon came to regret its decision to purchase these islands, with US president Herbert Hoover deeming the US Virgin Islands the “effective poorhouse” of the United States and a drain on the coffers of the metropole. In a series of 1931 remarks, Hoover—like the Danish before him—gestured toward paternalism and charity for the residents of these islands, when he concluded, “Viewed from every point except remote naval contingencies, it was unfortunate that we ever acquired these islands. Nevertheless, having assumed the responsibility, we must do our best to assist the inhabitants.”10 Despite this buyer’s remorse, the United States has retained possession of these islands, with 2017 marking the centennial of the purchase. The intervening years have seen a continued engagement with these events in the US Virgin Islands, including reenactments of the 1917 ceremony in which the Danish flag was lowered and the American flag hoisted up the flagpole. These engagements have gone largely unremarked on—and unnoticed—in Denmark and the United States but have been widely celebrated in the territory. Over the course of 2017, Denmark has attempted to grapple with its self-proclaimed “forgotten history” of colonialism in the Caribbean, with a number of museum exhibits and displays outlining the glory days of Danish imperialism.11 While this history may have been forgotten in Denmark, it has continued to inform the lived experiences of Virgin Islanders.

***

In Owning Memory: How a Caribbean Community Lost Its Archives and Found Its History, Jeannette Allis Bastian argues that commemorations and reenactments of historical events are demonstrative of a community’s identity.12 For instance, the reenactments—and annual celebrations—of Transfer Day in the now-US Virgin Islands reveal something about the continued engagement with these historical events on the part of Virgin Islanders. What can it mean that Virgin Islanders choose to revisit not the independence of these islands but their sale from one nation to another?

Figure 3. “The Three Queens.” Re-enactment in 2014 of the Fireburn uprising on St. Croix. Photograph courtesy VI Consortium.

Figure 4. An oil painting depicting the 1878 Fireburn uprising hangs in the US Post Office in Frederiksted, St. Croix. Photograph by the author, 2007.

These reenactments and depictions are, I argue, complicated. For instance, figure 3 depicts a reenactment of the events of Fireburn, a 1878 labor uprising by nominally free black people on St. Croix that resulted in huge swaths of the island being set ablaze. Figure 4 is an oil painting of the same event. The location of this painting has always struck me: it hangs prominently in the US Post Office in Frederiksted, a space that is perhaps the epitome of St. Croix’s existence as an American possession. I took this photo of the Fireburn painting in 2007; it seemed to me then—as it does now—that placing this depiction of rebellion, of reclamation, in a space that is administered by the US federal government is an act of resistance in and of itself.

Since 1917, Virgin Islanders have been in conversation among themselves about the implications of transfer. In 1992, the Virgin Islands Daily News published an editorial by local author Arona Petersen in which she outlined the relative merits of Denmark and the United States through the lens of food:

Like Vienna cake [for example], we took away the fruit jam that came with the recipe and instead used guava, guavaberry and pineapple filling—rum instead of brandy since we had so much on hand (even to wash the dead) to give the cake a different identity, so instead of “torte” it became Vienna. . . . You remember those little sweet breads we used to have for Lovefeast in Sunday school? I think that’s why they called it Lovefeast because everybody liked to feast on those little buns.

I think we’ve jogged our memory enough thinking about nice things to eat. Don’t forget another side that we forget now: Thinking about rich foods makes us forget some times when we didn’t have coal in the coal pot much less food for the pot, kerosene for the lamp and house rent squeezing until you feel your back is breaking.

It’s true what you’re saying, but look what we learned—fortitude, endurance, pride, value, self-respect and respect for others, a firm belief in God that never falters. We hold to all those things so it is we who got the best of the bargain, with all due respect to the Danes. It’s a good feeling.

God Bless America.13

This emphasis on hybridity, of getting by and making do, is representative of the position of Virgin Islanders: never consulted (or even, as the West End News piece demonstrates, clearly informed) about the sale and transfer of their islands, they have taken what is available to them—American citizenship and quasi-belonging—and attempted to produce an identity. All of this, of course, is to Bastian’s argument that moments of commemoration are telling. What does it mean, exactly, that Virgin Islanders continue to reenact and celebrate Transfer Day annually? On the day of transfer in 1917, certainly, there was reason to believe that freedom would be forthcoming, and that it would be “well-dressed and fashionable,” but one hundred years on, what—exactly—are Virgin Islanders celebrating? The year Arona Petersen’s editorial was published, 1992, was the seventy-fifth anniversary of the transfer—the “Diamond Jubilee.” As 2017 marks the centennial of the transfer, the government of the US Virgin Islands formed a centennial commission to manage the many celebrations scheduled over the course of the year.14 What, then, is the work of these celebrations, these reenactments and repetitions? Are these reiterations productive—an opportunity to alter the narrative, even slightly, in each retelling? The grammatical voice of transfer—of having been transferred from one party to another—is passive. Perhaps in these commemorations and reenactments, there is the hope of what Tina Campt has called an alternate grammar of futurity, a future that includes the voices of Virgin Islanders.15

Tami Navarro is the associate director of the Barnard Center for Research on Women and the executive editor of the journal Scholar and Feminist Online. She is a cultural anthropologist and is currently completing a manuscript titled “Virgin Capital: Financial Services as Development in the US Virgin Islands.”

1 “The Transfer. Special,” West End News, 30 March 1917; www2.statsbiblioteket.dk/mediestream/avis/record/doms_aviser_page%3Auuid%3A5d71f3cd-8bdd-4700-b37e-4307377f12ec/query/west%20end%20news%201917%20american%20colonies.

2 Tiphanie Yanique, Land of Love and Drowning (New York: Riverhead, 2014), 12, 14.

3 See Jens Larsen, Virgin Islands Story: A History of the Lutheran State Church, Other Churches, Slavery, Education, and Culture in the Danish West Indies, Now the Virgin Islands. (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg, 1950).

4 Gordon K. Lewis, The Virgin Islands: A Caribbean Lilliput (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 28–29. Importantly, Denmark’s abolition of the slave trade was not synonymous with the abolition of slavery in the Danish West Indies. “The 18th century was a period of almost unvaryingly upward growth in the number of slaves, coincident with Denmark’s decision in 1792 to abolish the transatlantic slave trade in 1802 and with consequent feverish importations during the ten-year grace period.” Neville A. T. Hall, Slave Society in the Danish West Indies: St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 3. While Denmark may have been the first European nation to abolish the trading of slaves, other European powers followed suit thereafter: in the British Caribbean in 1807; the Dutch Caribbean in 1814; the French Caribbean in 1817.

5 Norwell Harrigan and Pearl Varlack, “The US Virgin Islands and the Black Experience,” Journal of Black Studies 7, no. 4 (1977): 388.

6 See Hall, Slave Society in the Danish West Indies.

7 The Danish West-Indies—Sources of History, “Barbaric Punishment for Enslaved Laborers with an Urge to Rebel,” under “Barbaric Executions,” www.virgin-islands-history.org/en/history/slavery/barbaric-punishment-f….

8 Peter James Hudson, Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 15.

9 Harrigan and Varlack, “US Virgin Islands and the Black Experience,” 394. Similar racial shifts occurred in other island-colonies, such as the Dominican Republic and Trinidad and Tobago. See Frank Moya Pons, The Dominican Republic: A National History (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener, 1998); and Harvey Neptune, Caliban and the Yankees: Trinidad and the United States Occupation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

10 Herbert Hoover, “Statement on Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands,” 26 March 1931; online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=22580.

11 See Copenhagen Worker’s Museum, www.arbejdermuseet.dk/en/whats-on/exhibitions/stop-slaveri/; and the Danish Royal Library, www.kb.dk/da/nb/tema/dvi/index.html.

12 Jeannette Allis Bastian, Owning Memory: How a Caribbean Community Lost Its Archives and Found Its History (Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2003).

13 Arona Petersen, editorial, Virgin Islands Daily News, 1992; cited and translated in Bastian, Owning Memory, 58.

14 See www.vitransfercentennial.org.

15 See Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).