Mas’, Identity, and Isolation

Mas’, Identity, and Isolation

When I left Trinidad in 1999 I took much for granted. Peter Minshall. Carnival Tuesday nights spent waiting and waiting—like I didn’t know that he would make me wait—to see Minshall’s mas’ performed beneath the hard-earned, the sweetly deserved theater of Savannah lights. A mas’ that showed us to ourselves. A mas’ to soil our soul, and a mas’ to sanctify it. David Rudder. Our thoughtful Kaisonian who looked, connected, and pointed us in all directions. Historian, commentator, and prophet, Rudder moved the whole you . . . not just your feet. Abigail Hadeed. I recall her panyard photograph of a lone panman, hunched, intent, down in his own world, and yet the image dropping us into that depth, revealing that the communal act of playing pan, like playing mas’, like our response to music and to lyrics, is by nature spiritual, individual, solitary. Down in that distance, the panman was defining himself.

All taken for granted, for when I returned in 2009 there was no Minshall mas’ . . . and before long, no MacFarlane, either. For the masses, Carnival Monday and Tuesday were release valves—a two-day road fete of more skin than costume, monster music trucks, bright feathers and swim trunks, a clichéd and drunken letting go. And soca, Carnival’s signature music, with the odd exception, was high only on energy and redundancy. If this big mouth mas’ said anything, it was in general . . . merely a context to structure the band. It spoke neither to us nor to our time. Trinidad was plagued by the usual corruption but also by rampant crime and gang violence. More than ever, we needed someone to ask us who we were and to help us to ask ourselves.

I found Hadeed still capturing what we take for granted. Still photographing Ole Mas’ characters. Still seeking what remains distant. And in Trees without Roots she had acknowledged Caribbean communities in Panama and Costa Rica, descendants of the unsung who had migrated to Central America to work on the Panama Canal. Then in 2012, she directed Between the Lines, a short experimental film about Moko Jumbies. “Chasing Our Ghosts: Mas’, Identity, and Isolation” stems from my desire to speak with Hadeed. Call it a letter. A letter that opens out to something wider. Call it an adventure in the absence of that conversation.

* * *

“All my personal work for Carnival is shot in black and white, as opposed to colour. . . . I tend to go for the black and white, where I can control the image—I can get what I want. I know what I’m feeling, I know what I’m seeing, I know what I want. I’ve been photographing traditional mas since the early 1990s. Simply because it was Carnival. Most or almost all my photography . . . centres on the peripheries of life. I’ve always felt sort of isolated. . . . I’m always one of these satellites, on the outside. So all my work deals with isolation and not belonging. These characters used to belong in Carnival. Now it almost seems like they don’t.”

—Abigail Hadeed, “Carnival Captured,” Caribbean Beat, no. 83

I had the sense of a story, and all stories inevitably are about time. I was mumbling What was once your pain will be your home and I ache in the places where I used to play.1 I was still needing to talk about things I couldn’t talk to you about. How the Ole Mas’ characters today, the roots of Trinidad’s Carnival, have receded like ghosts, anachronisms in a Carnival that has become, in the words of Peter Minshall, “little more than noise and sex.”2 How I had already written to you that neglect itself can make much disappear. Disappear . . . not cease to exist. Think invisible or translucent. Think Ghost. How I looked up ghost to find returning memory and spirit and trace. How I looked up spirit and it was essence and consciousness but also to abduct or run away with in secret.

And I wanted these ghosts to retreat somewhere . . . somewhere secluded where they would not feel invisible or slighted or inconvenient, where they could exist truly, be real to each other and to themselves. Without knowing why, I thought of Carrera Island—where convicts were sent to quarry limestone back in the 1850s, and where a prison still stands in the midst of all that water. And carrera, it turns out, is Spanish for run or race or a course of study . . . though the island was probably named after some shipping agent who leased it in 1830 with a holiday in mind.3 But since the currents around Carrera were as notorious as its eventual prison, the island devolved from a getaway to where the reprobate were sent.

Carrera’s captives could be deadly men and for a time included a rush of Indians who had killed their wives. Using the crabs on the banks of Carrera, they blinded themselves hoping to be repatriated to India.4 Once back home, they believed their sight could be restored. Back home they would want their eyes opened. Back home where they need not see the ways they were lied to, the ways they did not make sense, the defeated context of all that foreignness in Trinidad where they were becoming foreign even to themselves. The Indian indentured laborers and their early descendants were ghosts, too.

Carrera, the sealed world of a prison further estranged on an island. It reminds, and it suggests, that on this small, motley island of Trinidad, there are those who are made invisible, those who vanish from our consciousness, those who are disconnected, those who for whatever reason are shut in or shut out.

But Carrera also held a fourteen-year-old boy who had killed his stepfather, his way of shielding his mother from this abusive and violent man. And a guard taught this boy to read and write and advocated for his release. When the boy became a man, he was freed only to reunite with the retired guard, both men sharing the same hometown of Siparia. The free man played Midnight Robber each carnival in a costume made by the retired guard.5 So Carrera felt more and more like the setting for my story—this story about time, about what is past and what is passed over, about what recedes in lieu of ending. Why wouldn’t these ghosts end up on Carrera, where maybe the spirit of that Midnight Robber would roam? Might his robber talk all those carnivals have been firstly about his stepfather . . . and then his years jailed on Carrera?

And you, I wanted you and your satellite self on a boat braving those currents for Carrera, seeking what you hope or know to be there, or just heeding some course mapped inside of you without asking why. Like the way a photograph that succeeds does so providentially, fortuitously, cosmically, all of it being composed in a split second. All composed through that lens, complete, you and the vagaries, the spirits, the secrets, within a rough border you call the edge of the film that is to me a back door frame you’ve been let in. Your images are by a woman let in. A woman granted something internal and eternal, trusted not so much underneath as into core. A penetration and suspension, and yet movement and wind and current. You said each image is about timing. Time again. You don’t have any when the instant comes; but if you capture it, that instant, it will be and it will bloom forever.

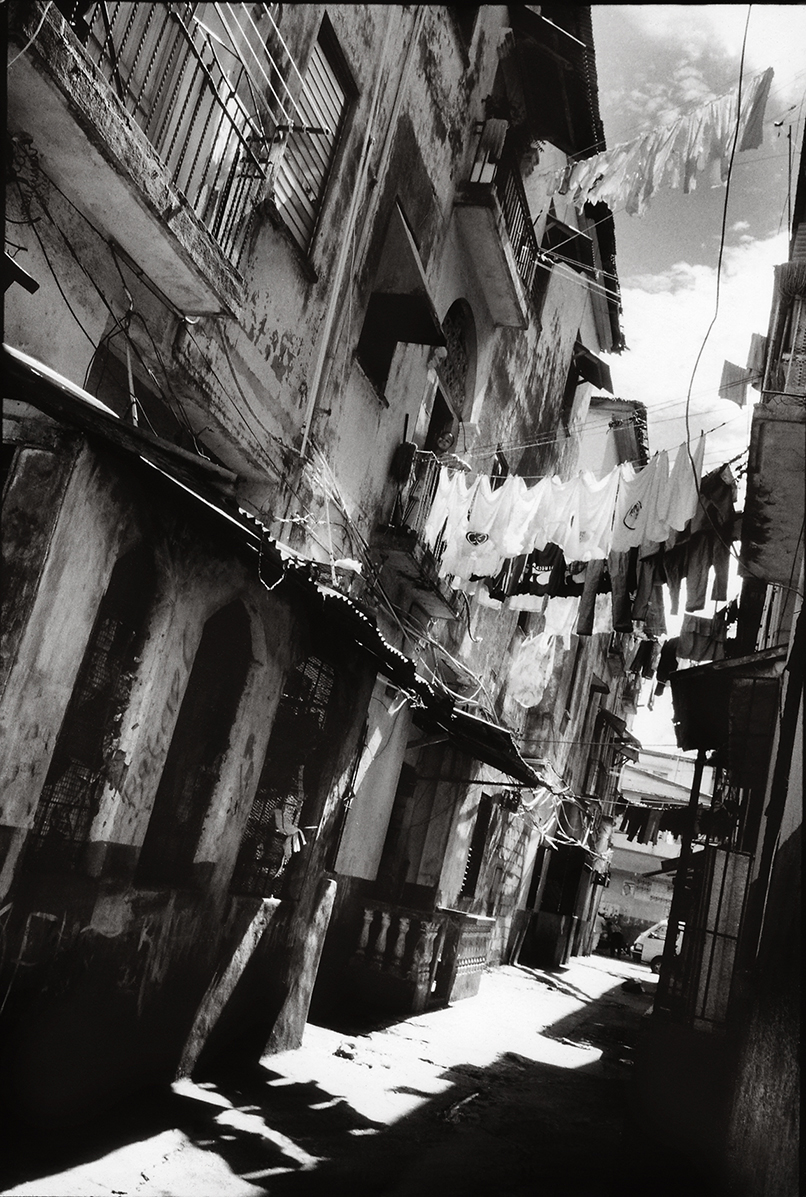

Figure 1: Abigail Hadeed, Laundry Lyrics, 1998; Colón, Panamá.

The image is free of time. Like that laundry on the lines. Such quiet in an image dubbed Laundry Lyrics . . . and not one face. Such crowding of directions, textures, everywhere lines . . . and emptiness. Until two people way down and way through . . . nearly beyond the shot of your lens; these barely bodies but all those clothes, light and light’s shadows. The lines linking the buildings above an alley to a stopped car; lyrics across the divide, relation, communication between buildings that might be behind scaffolding if they cared buildings like these instead of gutting then forgetting. But surely, softly, that Caribbean cotton singing between those Central American buildings, and you listening, merging with the black white grey all, you within that time and that time within you.

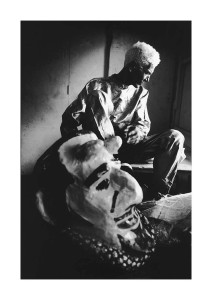

In a darkroom submerged in a damp sink or basin, drugged, drenched, an image is returning to you. This time a Bookman leans lacing his boot. Head bowed and turning away, he is old and near a window that is boarded up . . . though the light enters from somewhere. There is no trace of his book of souls, his biblical cape, or his finer clothes. It is quiet or he is quiet; he might be beginning his mas’, summoning what it takes to wear the Devil’s head, or perhaps he is done and has already put it down. The paper head is horned and painted and in profile with his own; his long clothes creasing, the paper face veined and pulling; his right side arcs with the headpiece; his left knee points with the horns. This thin man and this ponderous head . . . he has a waltz in him yet. The image is returning, rising up in its projected form, new again, almost tangible now, and how strange to see it and always then the jolt—what you thought you found has also found you.

Figure 2 (left): Abigail Hadeed, Bookman Benedict Morgan © 1995

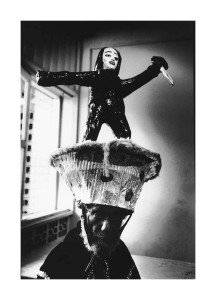

Figure 3 (right): Abigail Hadeed, The Midnight Robber-Esau Millington © 1995

And another small man, he is looking right at you, the Midnight Robber, whose shoulders he holds like a hood. He is old, and something has stopped him—staring, a nocturnal unshuttered at dawn; his mouth closed behind a coarse beard, a hunch to his neck and above it a headpiece with a Robber in miniature. Here he sprawls, the smaller Robber, all slick midnight and plunging dagger. Yes, here is the Robber above, the Robber beneath, the Robber . . . who you stopped and stopped for. The image, it is returning to you . . . slowly in safe light. The image you captured. The image a ghost. You forever chasing that ghost.

And finally I can see you, out on that thrown boat; and I see Carrera ever back in the distance. By days and by years we drift from each other; we drift from ourselves. Like forgetting, we drift homeless to faceless to senseless. Forever that ghost. And as the image always reminds, forever you on that boat. Another image soused and the shallow sea dusking, and you draining the color down to your black and white, your good, your evil, depth or light. Exacting but deceiving . . . because what you seek is not simple. You simplify to get at something incorporeal and essential and eternal. You simplify to get at something specific and infinite. You simplify to strip down to wait upon that mystery.

So you stop the boat. You dump the anchor. You sit there swaying in the salt water, looking toward the mass of an indistinct Carrera . . . and something, you don’t know . . . but something, because your skin stirs as if waking to a cold fire. And as you grope near your feet, he is upon you, the Carrera Robber; he is a voice standing over you on the bound boat. I guess my stepfather was like a white master, except he owned nothing but my mother and me. And since he only own we, he hate himself even worse. And when you hate yourself that bad, you hate who and what it is you have. You hate it till you kill it . . . unless it kill you. And after too long time could only come, so I slip a sweet axe in he skull. And it’s true—you’ve heard the story—you shake your head, shift, you are sorry . . . because you can’t quite remember, slide of light down the cape of another, another aging Robber, but there at the downtown carnival, someone should have taken this Robber’s last picture. And if you could only see him now, a form to drape around his voice . . . you’d brought your camera. Girl . . . (steups), I don’t need no costume now. You don’t play yourself when all you is . . . is essence.

Now hear it; what I saying. I went in the Savannah for Kings and Queens in . . . it was 1980, and that mad fella had conjured a Midnight Robber, a wide white web with a skull head, prancing and parading like a magga bandit cross with a spider.6 And I laugh for so, cause don’t mind Minsh use all that white . . . that off-white man knew it would be night and that though web will catch you, you could still see through, so the darkness stain like paint and the Robber was robber, yes, but he was the midnight, too. And that night if you or your camera was in the Savannah, then, girl, why you sorry? Is find you find me. Cause Minsh ent finish paint no costume, nuh; that was for we eye to do, and all of we Robbers was in that freak Robber . . . and you was in him, too.

Robber talk have a rhythm make every man jack dance, and you dance, yes, you dance, even when you frighten and sometime more when you troubled, you feel it and you made to dance; you dance till it is you catch your arm or your foot, till you can’t free and . . . funny, then is only listen, you listening like you have no more business with dancing. And could be it left over from Colonial days but if you want to kill a Trini, try curfew or State of Emergency. Restless, yes, they could take their hell, but they dead if you tape their mouth, done-dead if you tie their leg.

So long gone, still I can’t settle . . . This Robber, yes, I like the rest of you, I born talking but I different cause I could listen, too—not just to beat but to tune and to lyrics, too. That’s why sometime I swear like matchstick break in you ear. You love crowd and always liming, but let two of you be talking and—clear, you could hear it—neither one hardly listening. And every carnival that warm-over nothing does still have you jumping. Is only wine . . . re-wine. Find a bumper. Where the bumper? That is music? Or microwaving? Above you now he is laughing, I talking truth, I tired tell them boys . . . if you don’t tune a pan is just noise.

And you’ve been sitting there agreeing, thinking he should be more threatening; and God-yes he can talk but he’s no politician-lawyer. . . . You worry he’s too honest for a robber. But then his laugh hitches and falls into rasps. Hear what it is, girl. Listen to me good. You reach here quite behind God back just so I could run you, tell you pull up and get to hell back. ’Cause your place is by my place and . . . it can’t never be out here. And, girl, case you thinking I some kicksy Robber, ask the spirit still have the headache . . . ask my stepfather. Who don’t listen does feel. Catch you here again? I go deal with you for real.

Of course the Robber is right. Retreating is the last thing a Midnight Robber or any Ole Mas’ character would do. Born of resistance they can only serve it, persist no matter their numbers, fight for a scrap of street or stage, for the time enough to invoke what has past and what might still come. These characters don’t run. And since I’ve been telling you this story, then maybe you can hear me; and here I will pause, to return to Laundry Lyrics and the Bookman still turning, to beneath the dagger . . . to that stare of the stopped unshuttered Robber. Because if we could listen and listen with eyes open, we would see that these images are steeped in silence, and if we succumbed to that silence and stayed there, we would soon find ourselves, even down that divide underneath lines and laundry, in the presence of solitaries.

And for three moving minutes, there, in Between the Lines, Minshall’s Midnight Robber should be recalled to swagger, to wind, and to weave amid your Moko Jumbies.7 Between the Lines beginning with the even stranger stilted shadows of these prescient spirits, the trippiness of their little-noticed projections along with an unexpected score disorienting us from the start . . . , so when a skyward Jumbie with her jointless energy startles us in dancing, blazing color, we see something ancestral anew. Our Robber and our watchful protectors re-imagined and returned to us. Re-imagined to keep our ghosts, our traditions, among us and alive . . . to remind us that we are absolutely, in spirit and in body, an island, on which it is our right and our responsibility to define and redefine ourselves. In other words, play yourself. The lone panman. The lone masquerader. The paradox of mas’ . . . of being distinct though being together.

True, mas’ is derived from mascarade . . . the French word for “farce.” But this is Trinidad, so mas’ can be more than that. I prefer to think of mas’ as the Spanish word for “but.” Mas’ as conjunction and objection. Mas’ the fraught question. Mas’ the hinge between then and now; between now and not yet. Mas’ the movement away . . . toward. Mas’ as next. Mas’ the undefined alive.

Like the mix-up we all are, the Midnight Robber is African storyteller, European master, and American cowboy. On a Trinidad day we begin with the melee; we start in confusion and must scuffle toward meaning, and while this multiplicity is mass energy—think how wild birds converge—out from this ruckus comes the frustration that we might be too various. Carnival then is a concentration of our chaos, the clamor of all our color, noise, and movement. And I wonder if, deeper in it is this, our fundamental mixedness that compels you to strip back to black and white, to turn it down and tune into the space, to find something sure, something entire, not the spectacle of the presented but the clarity of contrast, essence, resonance . . . a pure presence at the core of our chaos.

Kathryn Martins studied writing at the University of Tampa and, after a ten year absence, has returned to her homeland of Trinidad. She lives in a valley where she sits with the hills . . . the backs and shoulders of what she will always be looking for. Her writing has appeared in the Kenyon Review’s KROnline and in Contrary Magazine.

___________________________

1 Emily Saliers, “Everything in Its Own Time,” from Shaming of the Sun, Indigo Girls, Epic Records, 1997, compact disc; Leonard Cohen, “Tower of Song,” from I’m Your Man, Columbia, 1988, long play record.

2 Sean Drakes, “Mas with Minshall,” n.d., seandrakes.com/interviews/mas-without-minshall (accessed 27 July 2014).

3 “Carrera, the Prison Isle,” Trinidad and Tobago Newsday, 5 June 2005.

4 “The Walls of Carrera Prison,” Trinidad and Tobago Guardian, 24 March 2013.

5 Ibid.

6 The Midnight Robber, designed by Peter Minshall, King of the carnival band Danse Macabre, portrayed by Peter Samuel Jr., 1980, arcthemagazine.com/arc/wp-content/gallery/peter-minshall/midnight%20robber.jpg.

7 Between the Lines, dir. Abigail Hadeed, 2012.