Cliff Lashley and the Anthony MacFarlane Book Collection

Cliff Lashley and the Anthony MacFarlane Book Collection

The following discussion is excerpted from two recorded conversations between Anthony MacFarlane and Ronald Cummings in December 2021 and January 2022. It offers a sense of the intertwined lives of a generation of young people who met at the University (College) of the West Indies in the 1950s in the context of a colonial Jamaica on the cusp of independence. This generation would go on to be part of the emergence of an independent Jamaica and the making of a Jamaican postcolonial diaspora in the mid-twentieth century.

Both Cliff Lashley and Anthony MacFarlane were part of this generation, and both lived in and away from Jamaica at different points in their lives. Here, we get a glimpse of their time as students at UCWI, and their transnational crossings in New York and in Canada. We also get a sense of their shared love of books, a devotion that informed Lashley’s work as a librarian and literary critic and inspired the making of what is now the Dr. Anthony MacFarlane Book Collection held at McMaster University. MacFarlane shares how this rare book collection is connected to and a legacy of his friendship with Lashley.

In 1957 I went to work in the Courts Office at Half-Way Tree. After some weeks the clerk of the courts, who was the boss, said to me, “Mr. MacFarlane, you shouldn’t be reading books, you should be working.” I guess people who come from the plantation are accustomed to giving orders. I took up the phone and called the university and said, “What do I have to do to get in?”

The UCWI [University College of the West Indies] was opened in 1948, so this would have been about ten years later. This was the context in which I met Cliff. At that time the halls of residence [on the Mona campus] included the female one, Mary Seacole Hall.1 Cliff was on Chancellor Hall. I was on Taylor Hall to begin with. Then the following year, we both moved onto Irvine Hall, which had become co-ed.

I had wanted to read honors in history, but to get into the arts faculty you needed a second language. I might have done Latin at St. George’s College, but Father McMullen [the headmaster] said I shouldn’t do Latin in the Senior Cambridge exams because it was not one of my strongest subjects.2 You can translate that to: he had the sin of pride. You see, he wanted the school to get the highest marks possible. Had I [received] a pass in Latin, I would have gotten in there [to read history], no problem, but I didn’t have the prerequisite. However, I could do sciences. For that, I was completely unprepared. There was a guy from Guyana who was very kind to me, and he sort of guided me. His name was Sammy Cummings, and he was a very good friend of Cliff’s. They both lived in Chancellor Hall. I believe they lived one room above the other, so they were close. And it was because of Sammy Cummings [that] I met Cliff and we became good friends. Sammy was a terrifically bright guy who was more interested in mathematics. He would go on to become a well-regarded teacher of mathematics at Jamaica College.3

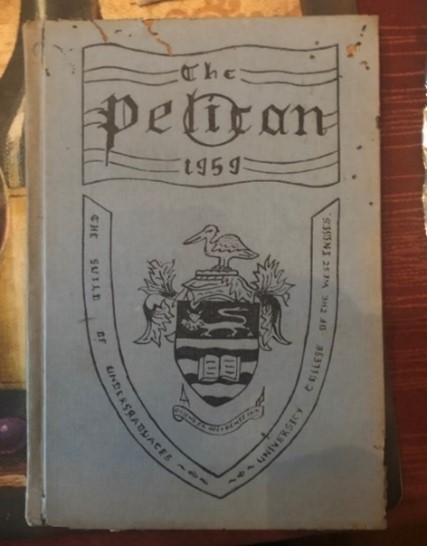

On the UCWI campus, Cliff was involved in many things and had very strong opinions about lots of stuff. Cliff’s one characteristic was that he could be very critical. They used to have an annual publication [the Pelican], and there is one that I have which has a thing about Cliff that actually describes him.4 Cliff was also enormously knowledgeable. I remember in his first year [of university] Cliff used to go down to the Junior Centre [at the Institute of Jamaica] to look at their books. In that first year at the university, he also gave a presentation on modern art, and Professor Sandmann, who was a lecturer in classics, said it was the best lecture he had heard on modern art.5

Figure 1. Pictured is a copy of the 1959 annual of the Pelican that contains a profile of Cliff Lashley. It is signed L. A. W. (possibly authored by Louis Wiltshire). From Anthony MacFarlane’s personal archives. Photograph courtesy of Ronald Cummings

Cliff came from Spanish Town. His father had a variety store. So Cliff was relatively middle class. My upbringing, on the other hand, was rural. I grew up on a small plantation in St. Mary on the north side of Jamaica. If you are on the North Coast and you get close to Buff Bay and turn inland, you have a fairly bad road, not paved. That takes you to Retreat. My grandparents owned the plantation. What is interesting is the background of my grandparents. An Englishman came to Jamaica in the late 1700s. He settled in this little town by the name of Retreat. Now this guy, Rigg, had a son with a Black woman. This was Richard Tyson Rigg. He was the father of my grandmother. So my grandmother grew up in Retreat with her sister and eight brothers.

When I first met Cliff, he was very censorious. That is the word I would use. He was very dismissive of me because he thought I was only interested in European things. This was quite true. I started reading when I was eight. My grandmother came from Kingston and handed me my first book. I opened the book, looked through it, and there were no pictures. I was disappointed. After a few days I sat down to read it and make sense of it. The book was Little Men.6 Later on, I read Tom Sawyer and then some very popular series of books—Nancy Drew, The Hardy Boys, and so on. So I was not really exposed to anything having to do with Black people or with the Caribbean until in 1968 when I decided I wanted to learn French. In order to learn French, I went to Paris. And I took a very interesting book with me, John Stedman’s Narrative of a five years’ expedition.7 It was about a man in the eighteenth century who went to Suriname to catch runaway slaves. That was one of the first books on Black history I devoured.

I first came to Hamilton [Ontario] in 1959. I originally came here on a ten-week holiday and ended up staying and completing a two-year pre-med course at McMaster University. After that I went to medical school at the University of Toronto from 1961 to 1965. After interning in emergency medicine in Hamilton, I took a year off to travel to Paris to learn French.

At the time when I went to Europe [in 1968], Cliff had come to Canada. I had reencountered Cliff in New York. He lived in Chelsea on West 22nd Street. On West 23rd Street, right at the corner there, is a very famous hotel, the Chelsea Hotel. (When Dylan Thomas was staying at the Chelsea Hotel he went out and drank himself to death.) I was in the Village buying shirts, and Cliff walked into the store with a guy from Spanish Town whom I recognized. We greeted each other, then Cliff told me, “I am coming to Canada to do my master’s in library sciences.” I asked, “When are you coming?” and he said, “I have an open ticket.” So I told him that I was going back the following day and he was welcome to come with me. He could stay overnight and I would take him to London [Ontario]. So he came over with me. I drove him to London the next day. The man he studied with at the University of Western Ontario was [James J.] Talman.8 He was Cliff’s mentor.

There used to be a train stop in Dundas [in Hamilton]. About once a month Cliff would take the train to Dundas and come down. I was living in an apartment then and working as a doctor. I would pick him up and he would spend the weekend. He would read my books and listen to my records. Because of my interest in piano, I used to collect records. Then one day he asked me if I would think about collecting [books] seriously. And we talked about it, and we decided that West Indian history would be what I would collect because I was interested in history and had known Dr. Elsa Goveia when I was at student at the University of the West Indies.

Now, having decided you were going to look at West Indian history, where would you go to find those books? The plan was that we would send [inquiries] to the bigger booksellers and ask them to send us catalogues, and the catalogues we were looking for were those that were called “Voyages and Travels.” Before I left for Europe, which was at the end of June 1968, I had a catalogue that announced a Jamaican newspaper for fifty-five pounds. So I sent them fifty-five pounds, went to Europe, and when I came back a volume was waiting for me. Have you heard of a man by the name of Edward Jordon? There is a statue to him in downtown Kingston. He was a Black man, and he was agitating for better conditions for the free Black and colored Jamaicans. Edward Jordon was one of the people involved in establishing the Mutual Life Assurance Society. This was the first time Jamaica had its own company. Before that, everything had to go to England. In 1828, he founded, along with Robert Osbourne, a newspaper called the Watchman and Jamaica Free Press.9 What I got for fifty-five pounds was a six-month run of the Watchman, from August 1830 to about March of 1831. Who knew that you could get that kind of stuff?

When I was in England (on my way to Paris, I stopped for ten days) I went into a bookshop run by a man called John Maggs. The shop had been in business for over a hundred years before. I walked into the bookshop, and I said, “I am interested in antiquarian books on the West Indies, with a special interest in Jamaica.” And John Maggs came to speak to me, and the first thing he said to me was, “Are you a dealer?” I said, “No, I am a physician.” So he asked, “How about these reprints?” I didn’t know they had reprints, but I thought they were great because I maybe couldn’t afford originals. So then he said to me, “Have you had lunch?” and we went to lunch.

At lunch he asked me about a professor in Jamaica at the University of the West Indies Hospital. And I said that [when I was a student] I would see him walking across the campus (but I wasn’t in the medical field at the time). It turns out his [Maggs’s] wife was a doctor. She had gone to Jamaica to work for a year with this guy. The fact that I knew about the West Indies, well, he was shocked. He asked his assistant to take me downstairs, and there in a storeroom, [floor] to ceiling were antiquarian books on the West Indies. First of all, I didn’t know that these books existed. I certainly didn’t know you could buy them. So I started picking books. I looked at the title pages, opened them, flipped a couple of pages, and if they spoke to me, I put them aside. So later I went upstairs, he went through them, and I got the nucleus of my antiquarian book collection. I asked him to mail them all back to Canada, except for one that I took to Paris with me [Stedman’s Narrative], and every evening I would read a few pages. And that’s when I realized that I was brought up on an actual plantation. And the plantation world is circumscribed. You have the Busha who lives in the big house, and the people who come to work on the place are all from the local village. The yard man, the cook, and so on. That was very interesting for me. After my stay in Europe, I also started collecting books in French.

I also have a Jewish background. In 1982 they had a book sale at Sotheby’s in New York. One of the things that they advertised was a set of Isaac Mendes Belisario’s Sketches of Characters, and their estimate for it was between $300 and $500.10 Cliff was in New York [and he went to the auction], and he called me when they had a break in the proceedings and said, “How high do you want to go for the Belisario?” I said $5000; they sold for $37,500. From that book sale in New York, I ended up with about thirty books, many of them [once] belonging to Aaron Matalon.

In 2007, they had a conference at Yale. The title of the conference was Art and Emancipation in Jamaica: Isaac Mendes Belisario and His Worlds.11 I had heard about the conference. So I went, and they produced a catalogue. (The catalogue has works by Verene Shepherd, Stuart and Catherine Hall, Kenneth Bilby, Robert Faris Thompson, and other notable names.) In it they had facsimile of the entire Sketches of Characters. In those days the catalogue sold for $50. I bought copies for all my siblings. Belisario was actually my great-grandfather’s cousin. I am related to him. In the facsimile there is also a list of subscribers [people who would have acquired Belisario’s Sketches at the time of production]. You will see the name D. P. Mendes. That is actually my great-grandfather. He was one of the people who subscribed.12

From a very early stage, Cliff collected all sorts of material, some of which I inherited. Once he decided he wasn’t interested in things, he would get rid of them. I inherited books from him. The Complete Works of William Blake, for instance, which he felt he didn’t need anymore. Some of his collection ended up at a place called RISM (Research Institute for the Study of Man), which was run by a man called Lambros Comitas. Cliff knew these people.13 He was probably one of the most influential people in my life. We weren’t always physically close, but it was always interesting to talk to him. Cliff was the one who, to his credit, said, “Would you consider collecting seriously?” Before, I was acquiring books, now I was collecting them. There is a difference. Cliff gets full credit for that.

Anthony MacFarlane is a retired physician living in Hamilton, Ontario. He is a graduate of the University (College) of the West Indies, McMaster University, and the University of Toronto. He is also a former president of Temple Anshe Sholom and a Jewish community leader. In 2012, Dr. MacFarlane was given the University of the West Indies’ Vice-Chancellor’s Award. Parts of his rare book collection have been donated to McMaster University, York University, and the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto. He is currently writing his memoirs.

[1] Mary Seacole Hall was built in 1957 to accommodate the increasing number of women enrolling at UCWI, Mona.

[2] St. George’s College is a Jesuit school in Kingston, Jamaica. It was founded in 1850.

[3] For a fuller discussion of Sammy Cummings and his friendship with Lashley, see Frank Birbalsingh, “Man I Pass That Stage,” Caribbean Quarterly 66, no. 4 (2020): 538–49.

[4] The Pelican student newsletter began in 1951, and the annual journal in 1955. The profile of Cliff Lashley that was published in the 1959 annual of the Pelican is part of “The Cliff Lashley Bibliography” included in this issue of sx salon.

[5] Manfred Sandmann was a professor of modern languages at the University College of the West Indies from 1950 to 1960. Frank Birbalsingh also recalls Cliff’s knowledge of art. In his essay on Lashley, he describes a particular encounter in England that involved Cliff’s demonstration of his detailed knowledge of British and European art:

To this day, one of the most memorable events in my own life remains an unforgettable “guided” tour of the old Tate gallery in London, in the mid-1960s, when, altogether without any plan, preparation or guide book, Cliff lectured me exhaustively, in riveting detail, on relevant details of history, society, politics and aesthetic features of texture, shade, colour, and whatever else he detected in as many paintings as we could cover during one Sunday afternoon. His encyclopaedic knowledge of British and European painting was one thing. Even more striking was Cliff’s sheer joy, his evidently unbridled pleasure in conducting the tour: as if he would be mortified should I miss the slightest detail in anything he said. He acted as if the paintings were his own work, and the two or three hours of our tour had transported him into what seemed like a spell, in a completely different world which he appeared to relish more than our own. (“Man I Pass That Stage,” 542).

[6] Little Men, or Life at Plumfield with Jo’s Boys, is a children’s novel by Louise May Alcott, published in 1871. The book is a sequel to the better-known novel Little Women (1868/1869).

[7] The full title: John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative, of a five years’ expedition, against the revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the wild coast of South America, from the year 1772, to 1777: Elucidating the history of that country, and describing its productions, viz. quadrupedes, birds, fishes, reptiles, trees, shrubs, fruits, and roots; with an account of the Indians of Guiana, and Negroes of Guinea (London: Printed for J. Johnson [bookseller], 1796).

[8] James J. Talman was a professor in the Department of History at the University of Western Ontario from 1939 to 1987 and the chief librarian from 1949 to 1970.

[9] See the video “The Watchman: The Story of Edward Jordan” from the National Library of Jamaica, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MkOojM8YdkU (accessed 10 May 2023). For a discussion of the impact and importance of this newspaper, see Candace Ward, “‘An Engine of Immense Power’: The Jamaica Watchman and Crossings in Nineteenth-Century Colonial Print Culture,” Victorian Periodicals Review 51, no. 3 (2018): 483–503. DOI:10.1353/vpr.2018.0033.

[10] Isaac Mendes Belisario, Sketches of Characters: In illustration of the habits, occupation, and costume of the Negro population, in the island of Jamaica / drawn after nature, and in lithography (Kingston, 1837–38).

[11] MacFarlane is referencing the exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art, 27 September–30 December 2007.

[12] Tim Barringer, Gillian Forrester, and Barbaro Martinez Ruiz, eds., Art and Emancipation in Jamaica: Isaac Mendes Belisario and His Worlds, exhibition catalogue (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007). For images of Belisario’s Sketches of Characters, see https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/orbis:4515511. The list of subscribers can be found in image 4.

[13] Lambros Comitas was an anthropologist at Columbia University. In the late 1960s, Comitas and Vera Rubin, also an anthropologist at Columbia, conducted research in Jamaica. Their study produced Effects of Cannabis in Another Culture: Ganja in Jamaica; A Medical Anthropological Study of Chronic Marijuana Use (The Hague: Mouton, 1975; Scotch Plains, NJ: Mouton/MacFarland, 1975).