There isn’t much I remember of that time, when my mother was pregnant with my youngest brother. But I do remember the slim silver crochet hook and how it fit snugly between her dark brown fingers. I remember that there were always balls of crochet thread all around the house, and the doilies she would make. I remember taking these doilies up and examining them, running my fingers over them. And I remember my mother’s fingers, always moving, always making larger and larger doilies. I remember, too, drawing close to my mother, wanting to learn how to make these doilies, and her showing me how to make a simple stitch, and then more elaborate stitches. I must have been all of eight or nine years old when I ended up with my own slim silver hook and my own ball of thread, because I remember the delight I took in having that thread in my schoolbag, just like I saw with so many women on buses in Kingston, their ever-busy hands pulling thread from their bags as they made their own doilies. The time on a bus when the eyes of a man and a woman were steady on me, before the woman gave out, “But mi Lord Jesus, this child here making good-good stitches too!”

Crochet was an art form that many women learned from each other, passing it one to another, learning it from watching each another, until they could read the patterns in crochet books. How ironic that these days, now that I am doing research on women’s textile traditions, that crochet remains one of the more elusive art forms to be found in Jamaica. Crochet is now considered too old-fashioned. Passé. So many pieces have been tossed out and destroyed. My mother, Marjorie Bishop, who now lives in the United States, does not have pieces of her own work from Jamaica. It is a history I am seeking to recoup.

Figure 1. Crochet by Marjorie Bishop

I spend time talking with my mother about crochet. Finding out how she learned it and placing her story and our family’s needlework story within a larger history. I find myself going back to Jamaica, as I always seem to be doing, to the tiny district of Nonsuch in the parish of Portland. A district where I spent just about every summer holiday as a child. Right beside the place where my grandmother lived in Nonsuch was an old broken-down building that everyone called the “Center.” (The games my siblings and I and all the district children used to play in the Center! We would hide out in the cupboards and throw rocks through the crumbling ceiling. The place was completely deserted. At night we thought the shadows meant that it was haunted.) But here now, I am learning from my mother and her aunts that this center was once a vibrant place where, among other things, crochet classes were taught. Other needlework skills. The dilapidated deserted Center, it turns out, was part of a program developed by Norman Manley to bring skills, including and especially needlework, to women in rural communities like Nonsuch.

A personal story gets framed in a larger history.

There was so much that my mother was passing on to me along with those early crochet stitches. There was so much the women were passing on to each other in those needlework classes at the Center.

And then there was the time I went home for my great-grandmother’s funeral. Her death, like my great-grandfather’s a few years before, ushered in the reality of death for me, for both me and members of my family. I was bereft. By then, writing had seeped into my bones. But being a visual artist? This was something I locked deep inside my chest. I felt I had no models for that kind of life; the only models I had were of professional women. I was going to be a medical doctor. It was the best of all the possibilities around me. Still, I was reading and reading and reading. And then I read Alice Walker’s collection of essays, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens.1

The context was American (I was now living in the States), but there were so many similarities to the rural Jamaican lives of my mother, my grandmother, and my great-grandmother. And so maybe I was primed to first be astonished and then gladdened at what I found of my great-grandmother’s life when, as a barely begun writer and a hidden visual artist, I returned for her funeral. Without consciously knowing it then, I had stumbled upon a model in my great-grandmother Celeste. Oh, the conversations we could have had! What I found was that my great-grandmother was herself a fantastic artist—she would use pictures from magazines and newspapers to create elaborate collages hung in her home; she grew a garden of roses so beautiful that she would cut and sell them to churches. But perhaps most important of all for me, I found the remnants of the art that she was most passionate about: patchworks. I gathered up what was left of her art, like gathering up so many parts and pieces and answers to and of myself, and took them home with me. Later, these very pieces would become the very core of my doctoral research. Because so much of what poor black Jamaican women like my great-grandmother have made has been neither archived nor recorded, one of the primary ways I have of accessing information on the work of women like her is through oral histories. Getting people who knew them and who saw them working to talk about them and their work. There was so much rich information waiting for me. In doing oral history interviews I found that people were fascinated by and often placed themselves in the research that I was doing. Some of the people I interviewed started looking anew at these old, old traditions while reaching for scraps of cloth to carry forward the tradition. Here, for example, my great-aunt Theresa Walker talks about seeing her mother, Celeste, make the patchworks that she herself would soon start making once more:

Figure 2. Patchwork by Celeste Walker

I see [my mother] making the patchwork. That is how me learn. Me watch her. Help her and see she take the pieces of cloth them and put them into the sizes. She sit down and sew in her spare time. See her all the time. She make more even than patchwork, because she make the slip them, you would call them old-time petticoat right with the big lace and she make tie head. She get different-different pieces of cloth and she tie it and she tie it like African, you know. You ever notice you see my mother with her head tie? Like a bow?

She do the patchwork on special occasions, like on Christmas. You know say she make all . . . you ever see the chicken feed bag them? First-time chicken feed what used to come in some pretty material? My mother take them, she make curtain . . . she make tablecloth, yes, and then she would cut out the piece of cloth like leaf and sew them . . .

With the patchworks she had [the material] beside her . . . on the bed and she choose from them. Take them up piece by piece and she sew them in. If she tired, she stop until another time. Because sometime she have to do other little things. She cut up her little old things that she have, or she would go to her sister who is a dressmaker and get some material.2

Figure 3. Patchwork by Theresa Walker

The daughters of Celeste Walker—my grandmother Emma Chin-See and my great-aunt Theresa Walker—would themselves go on to become notable patchwork makers. Theresa related that in making her patchworks she chose colors to match pieces of cloth she had. Throughout her interview she also talked about how sewing—patchworking in particular—was a soothing and calming activity for her, and she gave an impressive list of things that were made, ornamented, and decorated by the women in her family, including dolls and doll clothing, tablecloth, bed linen, and pillowcases. Emma’s daughter, my aunt Venice Chin-See Parchment, in the oral history interview I conducted with her, gave a particularly vivid description of how Emma made her works:

Mama, she always help [her mother, Celeste,] to do them, . . . so it becomes natural. [When] she started sewing them, . . . it’s just natural, they were so beautiful, and it was the same kind of intense look, [like her mother] looking on now, that she would have. And she was very interested in getting them done, and she would stay up at all hours of the night, morning, days, just spending time getting it done. . . . And she would choose her material very carefully, spread them out on the floor, make sure that she put them together, pieces by pieces, and of course she would stand back like a real artist, so she would put them on the floor, she spread them out, then she would stand back, look at it and sometimes she would call me over to say what do you think about this, and how to position that, just give me an idea of what she’s working with. So it’s really interesting seeing her work. And it’s the same intense look that she would have, it’s same thing, now that you are bringing me back to childhood, that [her mother] would have on her face. She did the work by hand solely.

. . . If you notice in some of the patchworks, she would start with this motivational piece, I would have to call it, and then work around that piece. So that piece may have several different colors and so she would match the different things to complement that piece that she start. So there is always a starting piece. And there is always in her head that motivational piece that she working with.

She felt very good in making these patchworks. I think it made her very happy. Coming down to where she got sick, I think it was therapeutic.3

Figure 4. Patchwork by Emma Chin-See

The quilts of Gee’s Bend have since become famous. There are clear parallels between Gee’s Bend in Alabama and Nonsuch in the parish of Portland and between the patchworks that would eventually come from both places. Both are small, remote rural towns of high poverty levels that saw electricity and other conveniences coming to them much later than other places. These were places where a largely black diasporic population had to learn very early on to make do with very little and to recycle whatever materials they had. Sewing held pride of place in both communities.

Much ink has been dedicated to looking at the “modernist aesthetic” in the work of the Gee’s Bend quilters and less to tracing the aesthetic effect of the narrow-strip weaving loom used extensively in sub-Saharan Africa, which, no doubt, migrated with enslaved individuals to the Americas. We see this aesthetic most plainly in the long, narrow strips of cloth utilized in John Canoe festivals in Jamaica. The more I research the tradition of patchwork, the more I am convinced this aesthetic is at work here, as well, with its use of clashing colors and rhythmic patterns. Furthermore, the symbolism of joining together bits and pieces from the discarded and the leftover that are utilized in patchwork, and the seeking to join together and make coherent the bits and pieces, is, of course, the story of Africans in the diaspora.

And so our mothers and grandmothers have, more often than not anonymously, handed on the creative spark, the seed of the flower they themselves never hoped to see: or like a sealed letter they could not plainly read.4

Figure 5. Photocollage by the author

Once, someone looked at one of my photographic collages and said, “I see so much of your grandmother’s and your great-grandmother’s aesthetics in the work that you do. Honestly, Jacqueline, I even see it in your writing.” I was especially intrigued. It is so hard for a maker to get critical about her own work, especially when engaged in the act of creation. You rely oftentimes on a critical outside eye to point out things that might be obvious to just about everyone else. But sure enough, I started seeing, once this person took the time to show me, how the layering of my own photographs was in fact very similar to the layering done in patchworks, and in fact how indebted I was to the aesthetic passed down by women in my family, more than perhaps I had realized.

And what, after all, is this essay that I have written if not a patchwork with bits and pieces from my own voice, voices of people I have interviewed, selected lines culled from Alice Walker’s essay “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” and images of the work done by so many women in my family. No, all our mothers and grandmothers and great-grandmothers are not famous, as Walker rightfully notes in the essay, but for centuries now they have been sewing and making work that should be.

Guided by my heritage of a love of beauty and a respect for strength—in search of my [great/grand] mother’s garden, I found my own.5

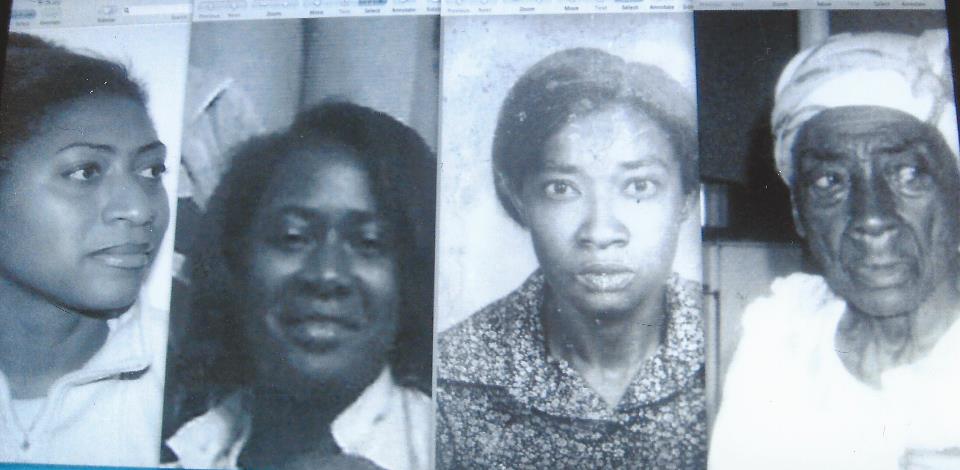

Figure 6. Left to right, the author, Jacqueline Bishop, with her mother, Marjorie Bishop, her grandmother Emma Chin-See, and her great-grandmother Celeste Walker. Photocollage by the author

Jacqueline Bishop, an award-winning writer and visual artist, was born and raised in Jamaica and now lives between Miami and New York City. She has twice been awarded Fulbright Fellowships, including a year-long grant to Morocco; her work exhibits widely in North America, Europe, and North Africa. The Gift of Music and Song: Interviews with Jamaican Women Writers (Peepal Tree, 2021) is her latest publication. She is also the author of, all from Peepal Tree Press, the novel The River’s Song (2006); two collections of poems, Fauna (2006) and Snapshots from Istanbul (2010); the art book Writers Who Paint, Painters Who Write: Three Jamaican Artists (2007); and The Gymnast and Other Positions (2015), a collection of short stories, essays, and interviews. The latter won the nonfiction category of the 2016 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature.

[1] Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens (1983; repr., Orlando: Harcourt, 2004).

[2] Theresa Walker, interview by the author, 19 and 27 December 2017.

[3] Venice Chin-See Parchment, interview by the author, 26 December 2017.

[4] Walker, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” in In Search of, 240.

[5] Ibid.